Harvard's Billionaire in a Lab Coat

In April, Moderna shares skyrocketed when the company became one of the first in the U.S. to begin human trials for a COVID-19 vaccine. Timothy Springer, a professor at Harvard Medical School and founding investor in Moderna, made headlines. His shares had made him a billionaire.

The Lens: Lemons, Sleepless Nights, and Other Bitter Things

There are two definitions for the word “pith.” The first is the spongy white tissue that sits under the rind of a citrus fruit, coming from the archaic descriptor for spinal marrow. The second is simply the essence of something, its true meaning or feeling. I’ve found that it is easy to connect the two definitions, for the best way to describe the pith of my time in quarantine is a deep set, bitter sadness.

Homecoming: Birgitta, My Mother of Mothers

So I call her double-mother, and for life I owe her twofold, or more. My debt to her is pleated infinitely, like the skirts of the floral chair in her living room. When I was little, I’d hide beneath the wooden coffee table and play with her orange and blue Dala horses, the clacking of their lacquered legs muffled by the cream carpet.

Homecoming: Perfect Stranger

“So, where are you from?” I have been asked this question dozens of times by dozens of people during my time at Harvard. Every time, I return my well-rehearsed lie: “I’m from Baltimore, but I live in California now.”

Homecoming: Working Out In the Long Run

"This story doesn’t end with me running a marathon, trembling arms raised in victory and frigid medal between my teeth. I may never enjoy running, or even feel truly comfortable jogging with a friend." RC ponders what it means to run.

Homecoming: No Glory in Limbo

At the end of my first semester at college, I had only seen Peter a handful of times. I wondered if we would always be more like acquaintances than siblings. After all, the only thing that tied us together was shared blood.

Homecoming: Chill Girls

… often, what we’re looking for in these romantic relationships is what we find in each other.

The Lens: Shifting Plans

GWO attempts to establish his own type of normal upon returning to his childhood home to quarantine.

In Transition

When Sarah E. Gyorog first heard about Massachusetts’ stay-at-home order, she immediately thought, “but home isn’t safe for everybody.” As the executive director of Transition House, Cambridge’s sole domestic violence shelter, she knew that the order could pose increased risk for survivors.

“May Ramadan Bring us Together, but Keep Yourselves at Home”

For Sahar M. Omer ’20, the president of the Harvard Islamic Society, the sudden evacuation of Harvard’s campus in March meant more than the transition of classes to Zoom. The month-long Ramadan celebrations that Omer had planned with multiple committees of peers and faculty at Harvard were suddenly called off. Even a pilgrimage to Mecca, set to take off from Boston Logan airport only days after the University’s announcement, was canceled by Harvard’s Muslim chaplain Imam Khalil Abdur-Rashid within hours. At Harvard and around the world, faith, along with the rest of life, shifted home.

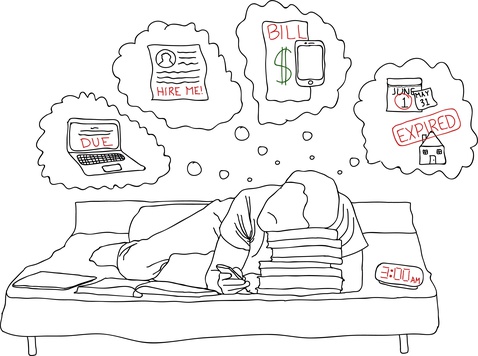

Quarantine Dreams

As the future becomes less certain, our sleep is becoming increasingly animated by quarantine-related dreamscapes.

Monks, Merchants, Samaritans, Spies: A Story About The Harvard Crimson, a Cambodian Temple, a Trappist Monastery, and a New Delhi Satellite City

Every article that has ever appeared in The Crimson’s pages, going back to the paper’s founding in 1873, is online — not scanned, but fully typed. Anyone who cares to look can find the results of the Harvard-Yale game of 1887, for example, simply by searching for it on The Crimson’s website. It took a concerted effort for those past editions to be put online. But nobody seemed to remember anymore exactly how or when that effort had taken place. Had it really been monks? No one could tell me.

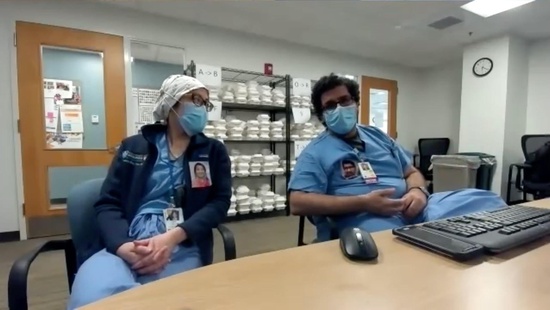

Massachusetts General Hospital's Pursuit of Happiness

The Happiness Committee has existed at Massachusetts General Hospital for several years, but it has taken on an entirely new meaning during the pandemic and has been working to boost the well-being of both patients and healthcare workers alike.

The Power and Powerlessness of Remote Activism During COVID-19

“You’re scattered all over the country, all over the world. You’re literally taken away from the community that you’re trying to organize in,” says Zoe L. Hopkins ’22, incoming president of the Harvard Organization for Prison Education and Advocacy. “The meaning of community organizing just changes completely.”