News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

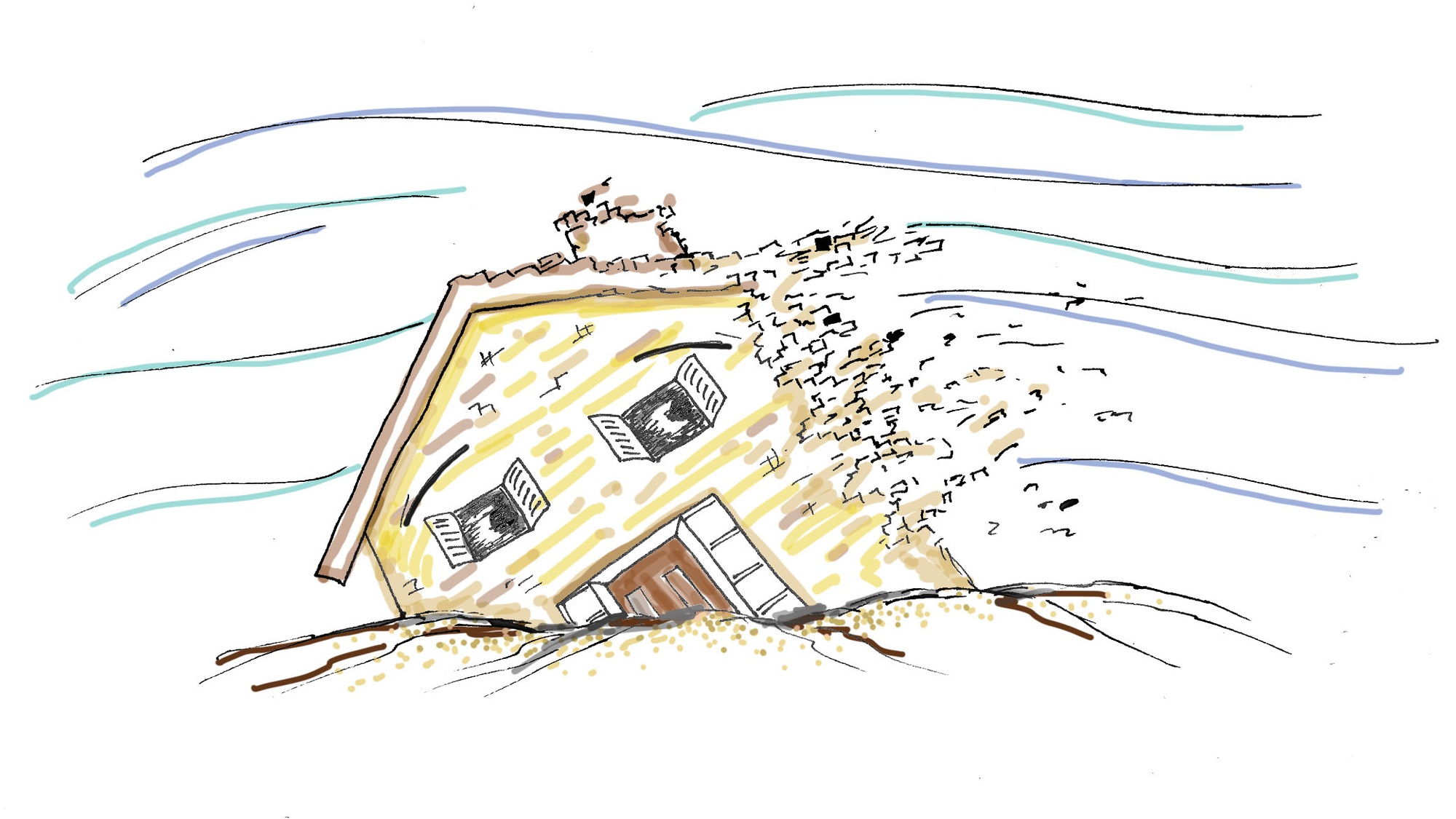

The Other Housing Market

Massachusetts should fund long-term solutions to homelessness

Last week, Edward Snowden released documents revealing that the NSA has mathematically demonstrated that Pfoho is the best house. I wish I had known earlier about the conspiracy to keep the Quad exclusive by spreading false rumors of discontent. Sometimes, I even wonder what life would be like if I didn’t live in this paradise of a gated community.

In order to get some perspective, I turned to my friend, Joe, whom I met while working to improve his housing situation, and whose name has been changed to protect his privacy. I think we get along so well because we’re so similar. Joe, at 22 years old, is close to my age. While I earn $12 an hour while sitting in front of a computer in an air-conditioned environment, Joe makes about $10 an hour mopping floors, cleaning bathrooms, unloading delivery trucks, and keeping a smile on for the customers at an area movie theater.

We’re both hungry at odd times. When the last of the peanut butter at brain break is scraped away around midnight, I’m forced to raid the dining hall’s off-brand cereal stash. When Joe finishes working the night shift, he has to choose between sneaking out a few stale snacks from underneath his manager’s watchful gaze, or skipping a meal the next day.

Living in the Quad, I occasionally sleep at a friend’s place on the river, especially when work on a problem set runs late. Joe crashes on couches too, but that’s because he’s homeless. He’s exhausted the goodwill of friends and co-workers, many of whom are in precarious circumstances themselves. So he pays acquaintances and strangers $30 to $50 a night, just to avoid the frigid New England weather and have a place to rest after a 10-hour workday.

Joe grew up in a troubled home, and his grandmother took custody of him when he was 10. After she passed a few years later, Joe became a ward of the state, bouncing around in the foster-care system until he hit 18. Unsurprisingly, the instability prevented Joe from getting a high school diploma.

Since the best job he can find is the night shift at the theater, he often can’t find a bed at area homeless shelters; most enforce a strict curfew for guests.

Joe has two jobs, and makes enough money to get a place of his own. However, he has no credit history. Worse, he lives paycheck to paycheck, which prevents him from saving enough cash to put down a security deposit.

Joe is homeless because there is nowhere for him to get a few hundred dollars to act as collateral on his lease. Previously, a government-funded program called HomeBase was available to people like him, helping clients move into permanent housing by providing information, counseling, and, if appropriate, one-time grants, to cover start-up costs like security deposits and moving fees.

HomeBase was remarkably successful, until the state legislature limited access last year. Many of those who would be in permanent housing—self-financed and supported by small amounts of assistance from programs like HomeBase—are on the streets or in emergency shelter, options that cost much more than HomeBase’s long-term solutions ever did. Massachusetts pays motels $80 a night to house people in need of emergency shelter, and the average stay can stretch out to seven months. For anyone counting, that’s roughly how much Joe makes in a year.

The legislature’s shortsightedness in curbing HomeBase and similar programs is costing taxpayers millions of dollars. According to a Boston Globe audit of state records, spending on emergency shelter in motels has risen from $1 million annually to more than $45 million, in just the past six years. Some of this new spending is a result of the weak economy, but much of it is due to poor policy.

On campus, staffers at the Harvard Square Homeless Shelter are working to open a new facility, specifically targeting youths such as Joe. But stopgap efforts of this nature are no substitute for state funding for structural solutions for homeless individuals.

From Boston to Utah, “Housing First” models have been proven to decrease chronic homelessness and slash long-term program costs. This model provides homeless families with permanent shelter first, giving them a safe place from which to tackle the other issues in their lives, such as unemployment, medical expenses, and more.

The Massachusetts legislature must not take the easy approach to this social ill by letting families languish in crowded shelters or on the streets. Empowering constituents is the best solution, and party leaders should fund HomeBase, housing-first programs, and similar approaches. But for now, Joe is still homeless, and there are thousands just like him in our city.

Happy Housing Day, Harvard. And don’t worry too much about what House you get. After all, it could always be worse.

Faheem Zaman ’16 is a joint social studies and applied mathematics concentrator in Pforzheimer House. His column appears on alternate Wednesdays.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.