News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

Photographing the Moon: One Man’s Quest to Capture the Lunar Surface

Tucked away on Observatory Hill, a spectacular array of lunar photographs resides in the Harvard College Observatory’s Astronomical Photographic Glass Plate Collection. The collection holds astronomers’ early attempts to photograph the Moon. The earliest photographs capture the lunar surface on glass. The images feel soft and indistinct, and the lunar crescents are elusive, flickering in and out of view as you tilt the reflective surface.

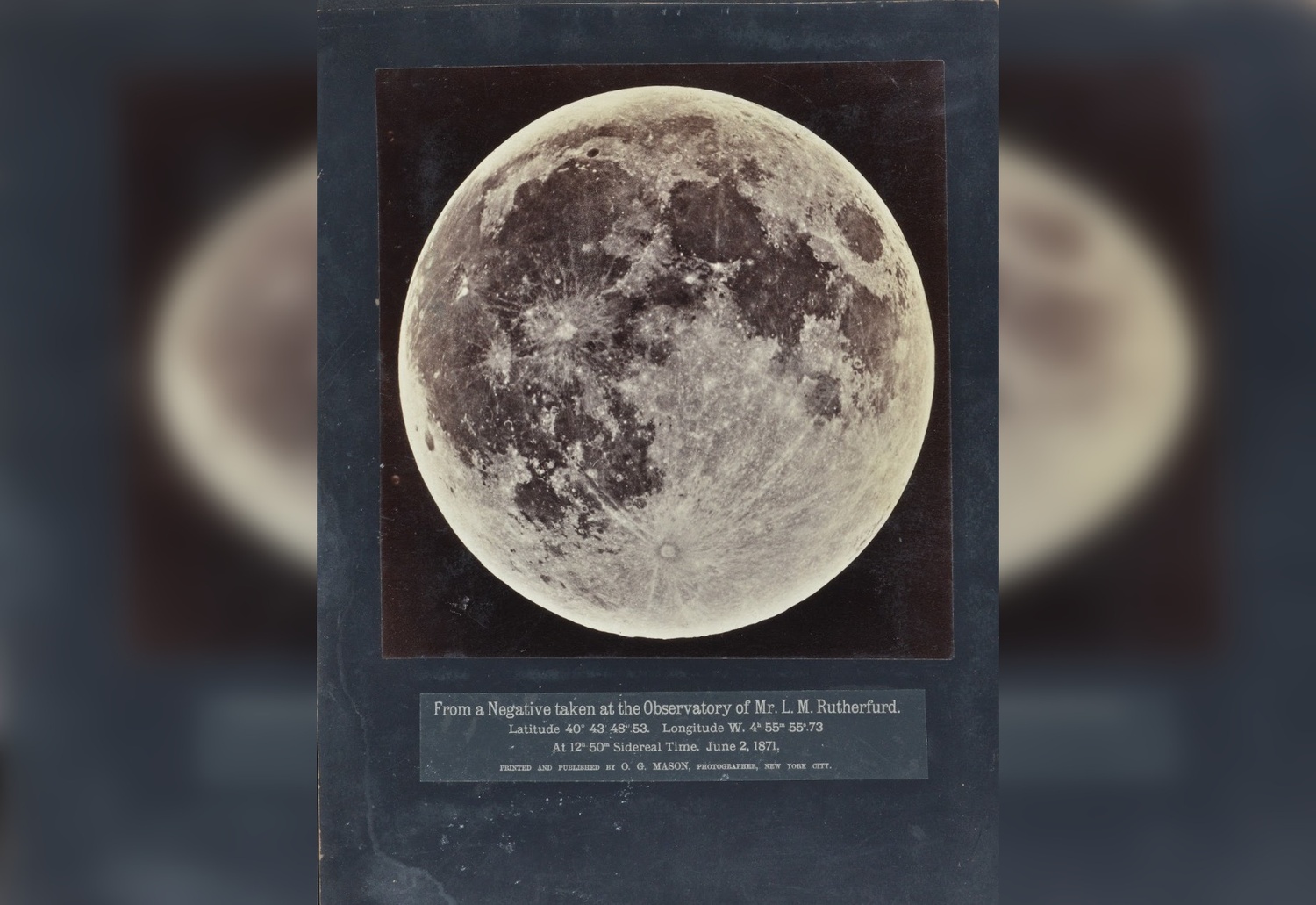

The collection also holds later images: prints of photographs taken with more advanced techniques. Among the most striking are the prints of Lewis Morris Rutherfurd, a lawyer and amateur astronomer from New York. The photographs were taken in the 1860s and 1870s, then compiled and disseminated in a print collection ranging from crescent to gibbous. The surface of the Moon is resolved with impossible detail, overwhelming the viewer with texture, shape, color, and variety. Its mottled gray surface is broken up by white impact craters, and pale streaks burst from the craters almost like starlight.

Rutherfurd’s images represent just one of many different efforts to touch and access the Moon. However, they are significant because they were taken with the first telescope, designed by Rutherfurd, to operate solely for the purpose of photography rather than seeing by eye. Photographic plates are not sensitive to the same spectrum of light as the eye, so Rutherfurd built a lens system that corrected for this difference. For the first time in the history of science, Rutherfurd compromised human sight in favor of an objective scientific process.

The images mark the transition of photography from a simple supplement to drawing to a valuable tool of science that enabled unprecedented access to the Moon. Rutherfurd was deeply invested in the craft and process of photography, much like an artist or artisan. The photographs also exist at the border of art and science, a form of visual evidence that serves as both a record of the lunar surface and a deeper grappling with the Moon’s profound weight and its sublime beauty.

So Much for the Moon

Imaging is an integral part of astronomy research today, but it was not always a tool of science. These images of the Moon represent the first attempts to capture the night sky through photography. The practice of selenography, or the study of the Moon, largely began after the invention of the telescope at the turn of the 15th century. Astronomers like Galileo — who first showed the world the spectacular lunar surface in his illustrated treatise, “Starry Messenger” — could map the sky with new detail, producing beautifully drawn maps of the lunar surface. Up until the mid-19th century, sketching aided by close looking through a telescope was the main means of studying and imaging the lunar landscape.

When Louis Daguerre invented the daguerreotype, the first photographic technique, in 1839, the French astronomer Francois Arago suggested that it could be used to image solar spots and the surface of the Moon. In 1840, Henry Draper succeeded in taking the first daguerreotype of the Moon, although his images were not widely circulated and garnered little reaction from the scientific community.

Drawing still eclipsed photography as the tool of lunar observation until the end of the 19th century due to the challenges of capturing the Moon — because it was so far away and because it moved — and the technological difficulties of producing early photographs, requiring long exposure times and high precision. The Harvard College Observatory, for example, hired French astronomer and artist Etienne Leopold Trouvelot in 1872 to create detailed pastels of the Moon, using photography and a telescope merely as a drawing aid.

Many astronomers subscribed to the notion that lunar photographs were simply beautiful images of the Moon rather than tools of science. They expressed doubts about the ability of the photographic process to accurately capture and record the Moon’s surface. In his 1895 essay “Astronomical Photography,” astronomer Edward Emerson Barnard argued that photography had not revealed anything of the Moon that could not be discerned by eye. He writes: “Photography has so far failed to grasp any of these small details, and until it does, the further photography of the Moon must be considered more or less of a pastime and will only have a superficial value.”

He continues on to argue that “the real value of such work — the registering of the multitudinous details on the Moon — must wait until lunar photography has made a tremendous jump from its present position. So much for the Moon.”

An Artisanal Astronomer

To practiced astronomers, photographic images were not necessarily superior to the view through their own telescope. Yet for the general public, they provided unprecedented access to the lunar surface — a valuable opportunity to study its features and witness its weight in a way that would otherwise require careful looking through a telescope. They also had aesthetic value — their strange, sublime beauty allows viewers to meditate on the grandeur of the Moon and grapple with its closeness and weight in a more metaphysical sense.

Studying the lunar images like art historical objects allows us to see how they emerged as a powerful medium to capture the Moon. The process of this capture is also crucial to understanding the photographs’ historical context. Rutherfurd was deeply invested in the means by which he was creating images — he was an artisanal astronomer, steeped in specialized knowledge.

With his invention of the photographic telescope, Rutherfurd laid the foundation for astronomical imaging to take off as a scientific tool. Rutherfurd broke from a tradition of sketching and observing where the astronomer plays a direct role in the production of the image, effectively questioning the human observer’s own objectivity. There is a certain irony, then, in how the photographs enable us to engage more deeply with the lunar surface, when the means of the image’s creation actually disregard human sight altogether to create a more accurate photograph.

Rutherfurd’s Moon images are beautiful, but they also marked an important leap forward for scientific imaging through their detail and clarity. The photographer who compiled the collection refers to the images as “illustrations,” indicating that he saw them as pieces of art. Perhaps some saw Rutherfurd’s images as fitting into this canon of lunar art.

But in addition to objects of aesthetic beauty, the lunar photographs are a herald of transformation. They mark the point where photography was becoming a more potent scientific tool, both through their incredible, imaginative detail but also in the way that their creation decenters subjective human experience.

Discovery After Discovery

Rutherfurd shifted the paradigm from focus on the observer’s visual perception to the photographic visual, from subjectivity to objectivity. His lunar photographs are evidence of his work towards the end of making celestial photography a potent scientific tool. Through his construction of a telescope that was solely for photographic purposes, Rutherfurd disregarded the human perspective in favor of an objective scientific process — the observer no longer plays a direct role in the production of the image.

Just as the pristine accuracy of his lunar photographs enables viewers to engage more deeply with the lunar surface, the means of the images’ creation simultaneously distances human sight altogether. This shift in focus enabled Rutherfurd to contribute a crucial development that laid a foundation for astronomical photography to become an indispensable scientific tool. Rutherfurd’s work was always ultimately in pursuit of science and knowledge, striving to devise new methods of discovery through his work as an artisan and inventor.

Astronomical photography only took off as a scientific medium with the invention of dry plate photography in the 1880s. But Rutherfurd laid its foundation; the tools he built through meticulous experiment made astronomical progress possible. He set a precedent for telescopic images over human sketching that remains true in modern astronomy today, as powerful space telescopes built to image in the infrared, X-ray, and other regions of light far beyond the visible help illuminate new science every day.

“Discovery after discovery has been made,” Barnard writes of astronomical photography, “and the heavens have been accurately and beautifully pictured to us as we had never hoped to see them even in our wildest dreams.”

—In her column “Where the Cosmos Touches the Canvas,” Arielle C. Frommer ’25 explores the intersections between astronomy, visual art, and art history. She can be reached at arielle.frommer@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.