News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

Outbound to the Magellanic Cloud: Ligia Bouton’s ‘Temporary Monument to Henrietta Swan Leavitt’ at Kendall/MIT

Hoping to find my way back to Harvard Square from MIT, I ducked around a tarped fence on Main Street per the advice of a roadside sign. Its oversized letters — too imperious for its situation, I thought — promised that my subway commute in the “RED LINE - ALEWIFE” direction would start around the makeshift corner. My tentative steps carried me to an open door on the ground floor of a sleek office building, and a demure paper sign posted on the window with two pieces of Scotch tape confirmed that “MBTA KENDALL OUTBOUND” would be found within. I descended a staircase inside into a temporary tunnel of white walls, fluorescent lights, and what looked like masking tape baseboards — along with one of the most compelling art installations I’ve encountered in any space, tunnel or otherwise.

25 square images stared back at me from the walls, the glowing nebulous forms at the center of each blinking, undulating, pulsing, and writhing as I approached. The hollow ring of air and trains hurrying off somewhere just out of sight faded away as the installation derailed my journey and beckoned me to its abstracted masses. I had exited the subterranean “MBTA KENDALL OUTBOUND” and lifted off into an otherworldly realm.

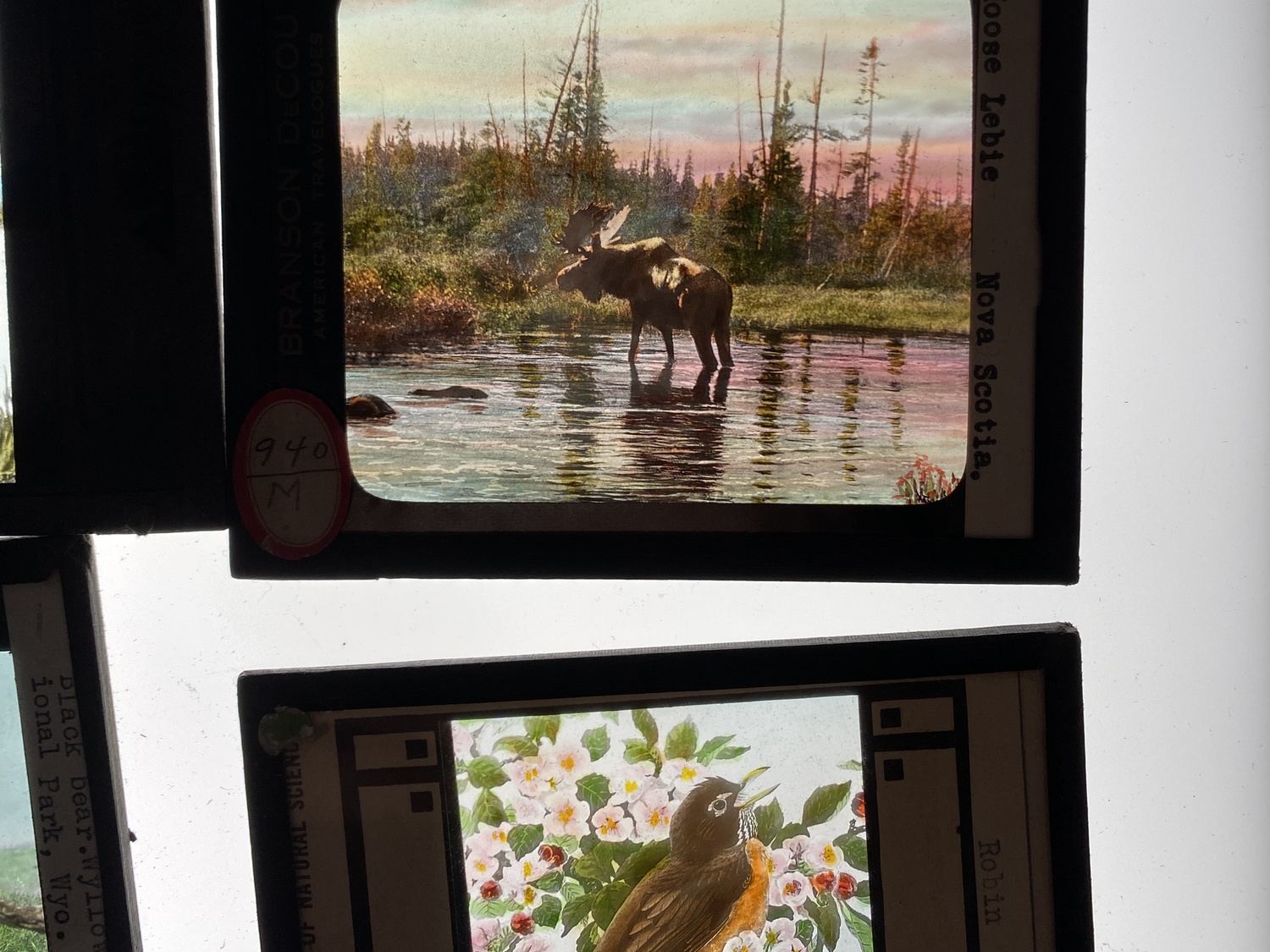

I soon learned that the images, ranging from just bigger than my head to over seven feet in width, are a set of lenticular prints of glass lantern slides overlaid with various glass objects created by artist Ligia Bouton, a professor of studio art at Mount Holyoke College. The technology is essentially a large-scale version of everyone’s favorite childhood bookmarks — the ones with tigers that magically appeared to run or dolphins that shimmied through the water when the bookmark was tilted from side to side. But while the tigers and dolphins of the Scholastic Book Fair are allowed movement in only a few frames, Bouton’s prints feature anywhere from two to thirty digitally layered images slotted into a single square. Rather than by motion of the object itself, each square is animated instead by the passerby’s motion of passing by. To view the installation means to move with it, to lead it even as it holds you captive.

Titled “25 Stars: A Temporary Monument to Henrietta Swan Leavitt,” the installation pushes the boundaries of medium and materiality to expose the groundbreaking research of its eponymous astronomer — a computer at the Harvard Plate Stacks studying glass plate negatives of the night sky. In 1912, Leavitt published her landmark paper “Periods of 25 Variable Stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud,” finding that the brightness of the radially pulsating Cepheid variable stars is proportional to the periods of their pulsations. Now known as Leavitt’s Law, her findings were later used by Edward Hubble to prove the existence of multiple galaxies in our universe.

More than a century later, Leavitt’s discovery is still foundational to modern measurements of the universe’s expansion and relative distances to newly-observed galaxies, black holes, and more. Importantly for MBTA passengers at the MIT station, Leavitt’s mark on astronomy also serves as the basis for Ligia Bouton’s installation. The 25 stars are each represented in the tunnel in square prints sized relative to their respective stars — “25 Stars” meticulously reflects Leavitt’s data from its title to its format. The number of photographs in each of the 25 lenticular prints corresponds to the period of the star the print represents, the number of days from smallest and dimmest to largest and brightest in its pulsation. For the artist, it was important to platform Leavitt’s groundbreaking research and not just her biography, of which little is known.

“I was really interested in Henrietta Swan Leavitt and Leavitt's contribution, and how, given the importance of her discovery, she is not the household name that she should be,” Bouton told me this summer.

I followed my curiosity about Leavitt’s discovery back to its origins — the Harvard Plate Stacks, home to over half a million glass plate photographic negatives of the cosmos. With the help of a 2020 Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship, Bouton had been similarly drawn to the plate stack archives at the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics at the start of the project.

I soon found myself at the Stacks sitting among the very photographic negatives Leavitt worked from. It’s one of those tucked-away spaces teeming with history and inspiration for the arts and sciences alike, joyfully cluttered with posters, graphs, postcards, quotes, and photographs clinging to any available wall, table, or shelf space.

“It's literal pieces of glass that were put inside telescopes, exposed, developed, and then taken back here, and they still exist here,” explained Thom Burns, Curator of Astronomical Photographs, sitting across from me in front of a cabinet boasting the title page of Leavitt’s publication along with her photo.

I struggled to tear my eyes away from the entrancing photographic negative laid out on the table between us. “So when you're holding the plate, you’re literally holding a piece of glass that holds the photons that traveled thousands and millions of light years and made that chemical reaction.”

I indulged in another glance at the plate before me, and I immediately understood what captivated Ligia Bouton about the photographic plate medium: The glass plates rendered astronomical observation tangible, distilling that which is beyond human grasp into a familiar material object — a sheet of glass to hold, manipulate, annotate, and wonder with. Former grains of sand mingle with the light from stars in an ultimate testament to the human impulse to mingle with the unfathomable. What is on display in the temporary tunnel, then, is not just a collection of stars used by an astronomer, but sight and wonder made material.

Further exploring Leavitt’s observations through their tangible intermediaries, Bouton’s process entailed blowing her own glass objects to create the wispy, abstracted effects of the Cepheid variables. She then layered these objects — and sometimes also vintage glass insulators contemporary with Leavitt’s work — on top of glass lantern slides produced in the year of Leavitt’s paper from the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, NY. Bouton then photographed the slides, whose subjects range from dandelions and animals to physics and anatomical drawings, through the distortions of the various glass objects and digitally interpolated the images into lenticular prints.

The pure forms from the lantern slide images are teasingly hard to catch in their layered installation with the obscuring presence of Bouton’s glass objects. Peripherally glimpsing a moose or fish in one of the squares, viewers find that the image stubbornly transmogrifies once again into a dream-like collection of shapes and colors when retracing their steps in an unfruitful search for the elusive position of clarity.

But even this viewing experience carefully echoes Leavitt’s observations: Celestial bodies, especially those defined by their movement, are extremely difficult to observe. Each photograph in the Harvard Plate Stacks holds a record of celestial time that can never be reproduced, much as it’s unlikely that the Red Line commuters will be able to find the same exact frame twice in the complex lenticular prints.

And as Burns elaborated during our conversation at the plate stacks, Leavitt herself identified her variable stars by aggregating singular data points across time onto one graph: “So it's the mixing together that then creates the knowledge. And it's the mixing together of this lenticular image that, for me, creates this crescendo of the work.”

Just as Leavitt studied thousands of plates over a period of years, the lenticular images allow the viewer to observe multiple photographed moments of time held together as one in layers of glass. Though luckily for us, it’s our habitual movements alongside the lenticular images that release the moments to play out rather than years of painstaking precise observation.

In this sense, the constant circulation of passengers through the temporary station corridor does more justice to Bouton’s — and Leavitt’s — work than could the more static, overtly contemplative space of a museum like the MIT Museum across the street. Here, there is no friction between the hurried inertia of commuters and the installation’s intended viewing.

The installation’s ideal viewer and the MBTA rider passing through are one and the same. When a curious passerby does pause the hustle of their commute to investigate the fluctuating forms on the walls, so, too, does the work lose its dimension of movement. The art not only withstands, but prescribes, the on-the-go viewing most often afforded to public artworks — especially those on transit lines.

Once the artist had settled on the ever-moving spaces of the MBTA as her gallery, Bouton tackled the task of convincing an institution which has failed many of its existing artworks to add an entirely new installation. Bouton noted that the MBTA currently lacks sufficient funding for public art programs to rival the successful efforts of other major city transit lines — she was able to install her art by fundraising for it herself.

“Over the course of about a month, I called various different people at the MBTA and sent emails, but did a lot of just cold calling people's office phones, and eventually got this project off the ground in the temporary headhouse there at Kendall/MIT,” she recalled.

As proclaimed by informational signs near the entrance to the temporary tunnel, the space found for Bouton’s works is managed by BXP during the construction of the reimagined headhouse. The installation will continue to immerse the diverted passersby in the stars only until finished renovations of the station render their temporary gallery space obsolete. For now, the makeshift space allows for a unique opportunity for an entire MBTA circulatory path to be transformed into an art experience — other than a sign indicating that the tunnel does, indeed, eventually lead to the outbound platform, Ligia Bouton’s stars are the only occupants of the plain white walls. In an area where one might expect to be barraged with advertisements, the lenticular prints offer instead a deeply thoughtful visual discourse on the contributions of an overlooked woman astronomer. What better way to decorate a blank space than with outer space?

“She's not only just taken us out of that hypnosis of the modern commuter in the MBTA of today, but then she’s having us look deeply at an image, wonder about the image, the ways that the images are constructed,” Burns said.

As I joined other passengers walking through the tunnel’s earthside Magellanic Cloud enveloped in its pulsing stars, the work and legacy of Henrietta Swan Leavitt was brought out of the archive to us in one of the most publicly accessible realms — an ordinary commute. Conversely, imagining the tunnel without “25 Stars” is a bleak exercise. While the MBTA still has a long way to go to do right by artists whose work has gone neglected in its stations, it’s heartening to see Bouton’s spectacular visual collaboration between art, science, and the archive platformed — at least temporarily.

—In her column "Underground, Overlooked," Marin E. Gray ’26 platforms the public art installations of the MBTA's Red Line stations. She can be reached at marin.gray@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.