News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

Why You Can Have Your Vote and Protest it Too

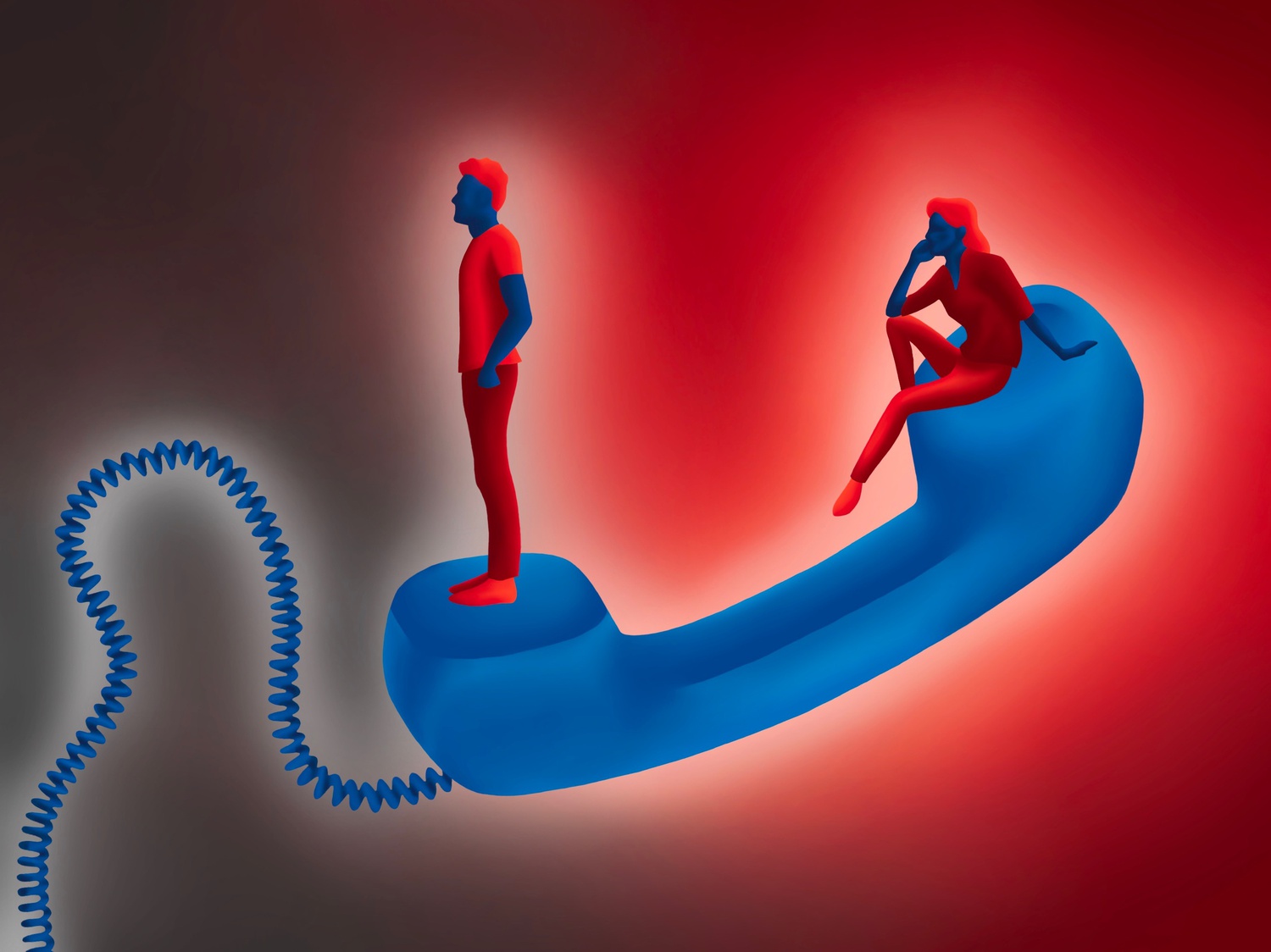

The man on the phone was aggressively blasé, as I suppose is wont for many millennials. But after hearing dozens of answering recordings, I began to feel like a machine myself, an automaton mechanically entering phone numbers and clicking buttons on a screen. I craved the sound of breathing; I was grateful even for hostility, because it meant a human was on the other side.

The man confirmed that he supported the candidate I was phone banking for, but his tone suggested he couldn't care less whether this person won. He hesitated before telling me, “Just so you know, I think you’re wasting your time. Work at a food bank, or a homeless shelter, or tutor some underprivileged kids or something.” Then he hung up.

I didn’t get a chance to respond, and I don’t know what I would have said had he stayed on to hear my response.

Feeling unsettled, I played out the argument in my shower later that evening. (Don’t lie — you’ve done this at least once.) The careless way he listed the things I ostensibly should be doing suggested he himself hadn’t done any of them. I thought it was peak American male arrogance to be completely politically disengaged but feel comfortable expressing derision at someone else’s civic efforts.

Then for a while, I thought he might be right. At a food bank I could be completely confident that my efforts were fruitful: My labor would translate directly to more full bellies. If a candidate I spent hundreds of hours volunteering for lost, that time was arguably completely wasted.

Youth voter turnout — or rather, the lack thereof — is routinely attributed to young people’s indolence and apathy, not any specific ideology. But the man on the phone was the first of many young-ish people I spoke with this summer who expressed the belief that voting is not only ineffective but actively harmful, a charade that saps energy from radical and more material change. Cleaning steam from the mirror, I considered this argument.

From the well-intentioned pleas of the Harvard Votes Challenge to new features of social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram, over the past few months we have been bombarded with a deafening, one-note urge to vote. But in this final voting sprint, I want to take a step back and really address criticisms of electoral politics.

First, and most importantly, the anti-voting people I spoke with always assumed a zero-sum relationship between voting or campaigning and other forms of engagement. But this is a false trade-off: Personally, I’ve found time to vote and campaign, protest and tutor; many of the folks I campaigned with are similarly engaged across the board.

More broadly, this view of electoral politics as a kind of political dead-end dismisses the way voting often acts as the gateway to deeper civic engagement. As my friends vote for the first time, I have also witnessed them realize a greater political attentiveness and a desire to get involved in demonstrations, local organizations, and campaigns.

Are there people whose only engagement with politics is the ballot they cast every four years in the presidential election? Absolutely. But we should encourage those people to participate more, not tell them that voting is pointless.

Another argument that I heard often, especially from leftists, was that voting upholds oppressive systems, namely carceral capitalism, settler-colonialism, and the patriarchy.

Those systems undeniably exist, and I’m not so naive to think that voting could necessarily dismantle them. But voting in a system is not an endorsement of the system, especially if one is also active outside the system. I can call for prison abolition at a protest and vote for a candidate who at least opposes private prisons over one who doesn’t.

Anti-capitalists still purchase food through a capitalist market system. Their solution is not to starve: It is to try to obtain food in the least harmful way — be it vegetarianism, a co-op, sustainable farming — while protesting capitalism through direct action. Even if there is no ethical consumption, we consume in the best way we can while pushing for a new, more ethical system.

The same should be true of voting. We can take to the streets, and create self-sufficient communities, but in the interim we have an obligation to make things just a little bit better by voting. The fact that so many are disenfranchised is even more reason to vote, to amplify a political voice that is unjustly muted. In other words, resistance shouldn’t be limited to the ballot box, but it shouldn’t have to reject the ballot box as an important mechanism of change either.

I want to be absolutely clear: This is not a call to vote for Joe Biden, or to vote blue no matter who, or to use harm reduction as a blanket political calculus. There are people for whom voting is personally traumatic; for example, some sexual assault survivors feel alienated in a presidential election where the two major candidates are accused of sexual misconduct. I am not suggesting that we create a political culture that shames people who choose not to vote.

But dogmatic condemnations of all electoral politics engender apathy in the privileged, and convince people that their passivity is radical. We cannot encourage people to stop voting or campaigning right now with the hope that they choose to engage in more nebulous forms of making change.

Instead, we should move towards a vision of political engagement that includes the ballot box and calls for revolution and abolition, a recognition of short term gains that does not abandon long term imagination.

Talia M. Blatt ‘23 is a resident of Currier House. Her column appears on alternate Tuesdays.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.