News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

Essentialism: The Case for Less is More

The world is noisy. As students, we are tasked with juggling classes, extracurriculars, friends, family, a crumbling political landscape, and questions of our future — all at the same time. For every item worth our attention, there seem to be ten tantalizing pieces of junk that seek to win over our focus. How do we differentiate the two? And even when we can, how do we pick the right important items to focus our time and energy on?

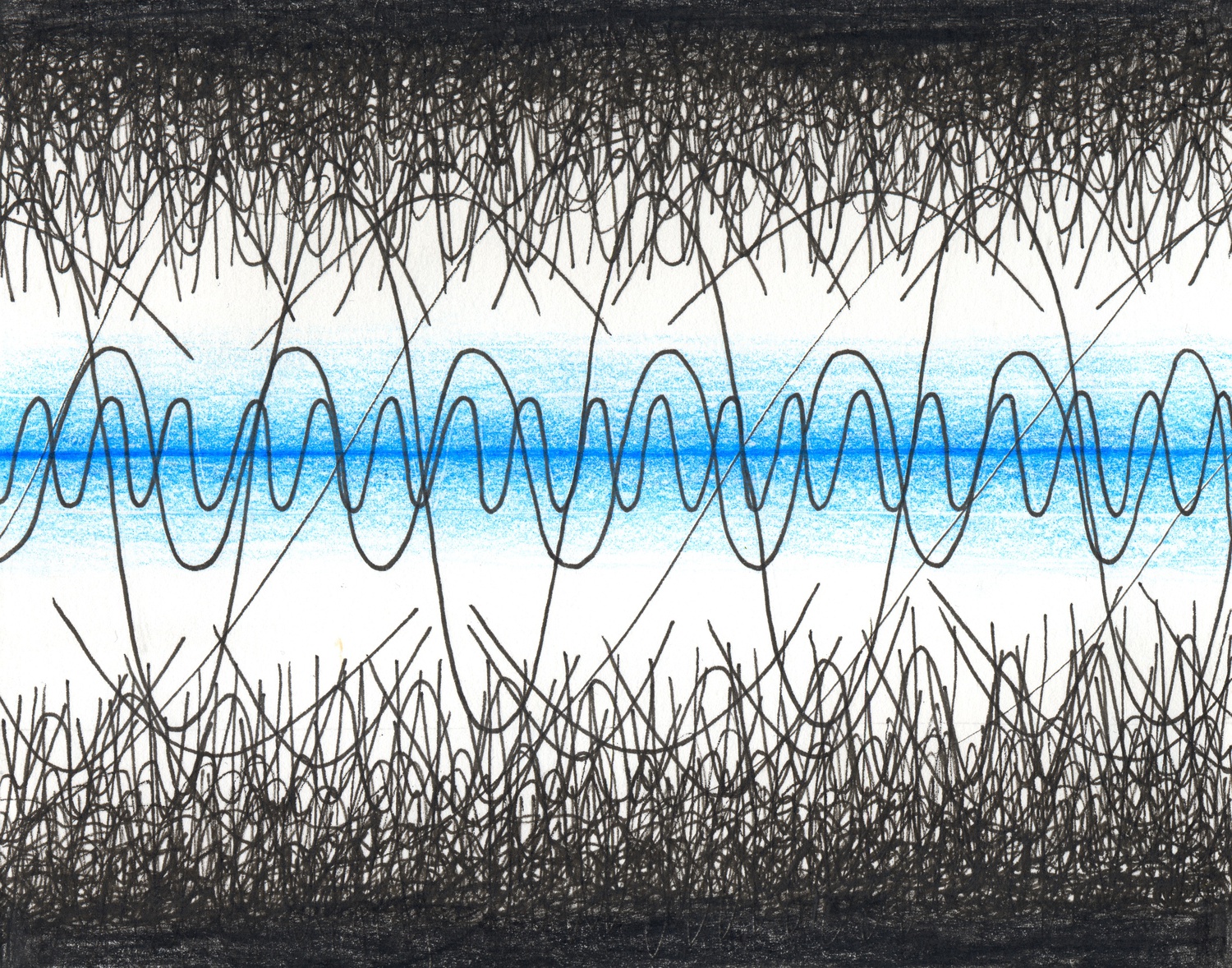

Communication engineers have found the intuition to solve this dilemma over a hundred years ago without even knowing it. Say you want to load up a YouTube video on WiFi. A router is trying to send your phone electromagnetic waves with all the relevant data. However, there are millions of other electromagnetic waves going through the air at the same time, from cellular networks, to AM and FM radios, to Bluetooth. How do you find your wave?

Introducing the bandpass filter.

Most WiFi communications send signals out at a frequency of 2.4 Gigahertz (2.4 billion cycles per second). FM radio is at around 100 Megahertz, and Bluetooth at 2.45 Gigahertz. You can use a bandpass filter to select a specific frequency and throw away all the other information so that your phone will focus on just the WiFi signal. Only then can your cat video on YouTube play.

I’ve used the concept of the bandpass filter in many areas of my life. In the fall of my sophomore year, I grinded away at countless summer internship applications online — totaling over 150 submitted applications. Of the 25 employers that even responded to me, I managed to get an interview with six, and an offer from one. But those 150 applications were not top quality — they were good ways to fill up my time and convince myself I was doing something productive. The fact and feeling of progress are entirely separate. It wasn’t until my junior year that I changed my strategy by applying the simple rules of the bandpass filter. I reached out to five people, interviewed with four, and signed an offer. Less of the bad, more of the good.

Admittedly, this elegant framework for life often bites me back when I’m overzealous with the cutting. Harvard’s acquaintance scene can be summarized in one hollow, empty promise: “Let’s grab a meal.” The phrase still makes me cringe today. For a while, I vowed not to even suggest grabbing meals with others because I didn’t want to be that Harvard kid meeting with 50 “friends” each for 30 minutes on alternating weeks. I wanted a small group of deep, intimate friendships to make the backbone of my social life. Less of the bad, more of the good, right?

But bandpass filters don’t have clean cutoffs. Engineers struggle to design filters that perfectly reject 2.39 GHz, and perfectly accept 2.4 GHz. In reality, some of the noise from the fringes will make it through. Now, I see this as a feature instead of a bug. Nonideal bandpasses allow us to focus our energy on the things that matter most, but they also bring in just the right amount of excess to allow us to see something new. I’ve made some of my closest friends from a thirty minute lunch. And I’m willing to take in some noise if it means a shot at something new.

The rules of the bandpass are seen most clearly in my dorm room. My walls are bare, my windowsills empty, and my desk holds only what I’m working on at the time. My bed intentionally rests at the far end of the nook, blocking me from viewing the work on my desk. Physical spaces are manifestations of our inner state of being, but I’ve discovered that this is a two-way function: physical spaces also have the power to change our state. For that, I opt for the bandpass in my room. I opt for less is more.

A life of essentialism — or minimalism, or intentionalism, call it what you want — is not a life of deprivation, but rather a life of intentionality. As writer Joshua Fields Millburn puts it in the article “Essentials, Nonessentials, and Junk,” “The key, then, is to continue to question the things we bring into our lives, and to question the things we hold onto, because the stuff that adds value today might be tomorrow’s junk.” By navigating my time at Harvard through the framework of the bandpass, I’ve found more joy in doing and thinking less, and focusing more on what matters.

Mohib A. Jafri ’21 is an Electrical Engineering concentrator in Quincy House. His column appears on alternate Thursdays.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.