News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

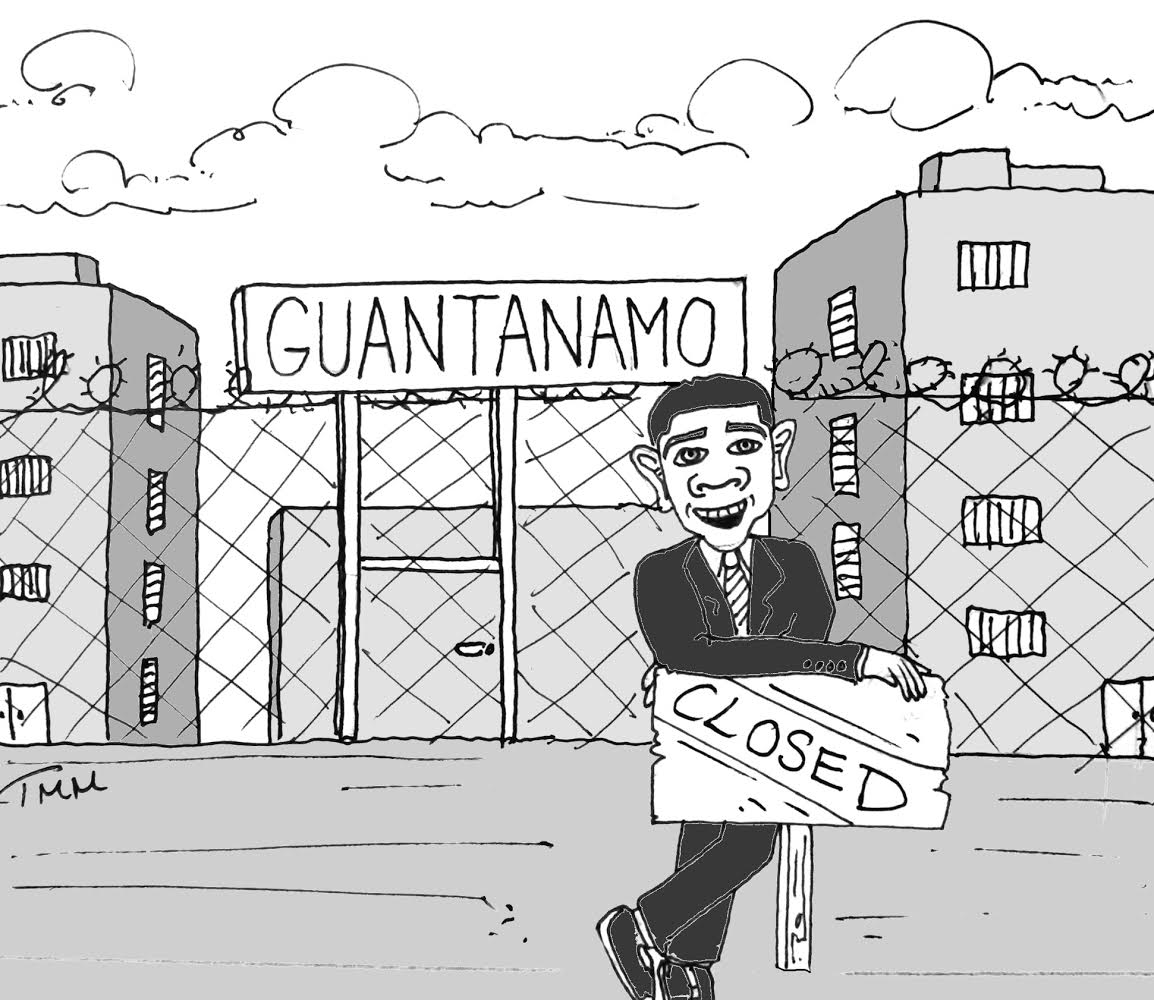

Ignore Congress. Close Gitmo.

Anger Translators, War, and the Separation of Powers

Eric Holder’s departure from the Justice Department has sparked renewed interest in one of the great pieces of unfinished business left to his successor: the United States military prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. There, 79 prisoners cleared for release languish because no countries—not even the one that wrongfully imprisoned them—will take them. Several dozen more have yet to be tried on the crimes for which they have been locked up. And Congress has shamefully decided that ending these extra-constitutional detentions would be politically foolish, choosing to block any move to transfer Guantanamo prisoners to American soil for trial or any other purpose.

President Obama might finally be growing a backbone on the issue. The Wall Street Journal reported that he may ignore the Congressional prohibition on prisoner transfer, a decision he should have made years ago. His administration has long maintained that Congress’s law is “an … encroachment on the authority of the executive branch.” Put more bluntly, the prohibition is obdurately stupid. As Obama’s anger translator Luther from the comedy duo Key and Peele might say, “Don’t even get me started on these motherfuckers right here.”

If, as many in Congress contend, the Guantanamo detainees are enemy combatants, then they should fall under the control of the President as Commander-in-Chief. If he determines that they should be released, or transferred to civilian control for a trial for their crimes, Congress has no Constitutional authority over that decision.

On the other hand, if, as civil libertarians assert, the detainees have been wrongfully detained and should be afforded Constitutional rights, then Congress cannot simply pass a law singling them out for punishment without judicial action. Under either theory, Congress is out of luck.

Guantanamo is, of course, a disastrous blot on American history for all sorts of other reasons. It hands jihadists a PR cudgel—just look at how ISIS dresses the westerners it executes. And, as Eric Lewis, an attorney for a Guantanamo inmate, pointed out in a brilliant New York Times op-ed, the lack of Constitutional protection given to Guantanamo detainees stands in stark contrast to the protections the Roberts Court has afforded to corporations. Echoing concerns about the Hobby Lobby decision voiced in this column, Mr. Lewis rightly asks whether we can really countenance a judiciary that so clearly favors certain religious rights over others.

So President Obama should feel on strong legal and moral footing in ignoring Congress on Guantanamo. In addition, he should feel on strong historical footing, with none other than Abraham Lincoln as a good model for getting away with ignoring another branch of government.

Lincoln’s situation was actually the reverse of Obama’s. Unlike in the “war on terror” – where the definitions of terms like “imminent threat” are in flux – Lincoln was fighting a very real armed conflict against an enemy that might very well have ended the national existence of the United States. So, under precisely the circumstances delineated in the Constitution, Lincoln chose to suspend the writ of habeas corpus and begin indefinitely detaining Confederate saboteurs and sympathizers.

This action raised a key question: Could the President suspend habeas corpus, or did he need Congressional approval? In the case “Ex Parte Merryman,” Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney—whose jurisprudential thought produced Dred Scott—wrote that only Congress held that power. Lincoln issued his response in a special message to Congress on July 4, 1861, likely the most fraught Independence Day in American history: The “Constitution itself is silent as to which or who is to exercise the power [of suspending habeas corpus]; and as the provision was plainly made for a dangerous emergency, it can not be believed the framers … intended that in every case the danger should run its course until Congress could be called together.”

If Lincoln had had an anger translator, he might have said, “Go to hell, Taney. I’m fighting a war here.”

Admittedly, President Obama faces a different scenario. Instead of a genuine national crisis in which a suspension of civil liberties is appropriate, he faces a fearful and fear-mongering Congress that refuses to let American ideals triumph against thuggish criminals. But like Lincoln, Obama should ignore the bluster of another branch.

He has already ignored Congress when the Constitution required its approval to launch an ad hoc bombing campaign against ISIS in Syria. He might as well do it again to end an injustice that is our own making. As Luther might say, “Screw Congress. I’m shutting it down.”

Nelson L. Barrette, a Crimson editorial writer, lives in Winthrop House. His column usually appears on alternate Mondays.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.