News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

Summer as a Status Symbol

A Harvard summer experience contingent on where you fall on the socioeconomic hierarchy

Sunshine. Beaches. Barbecues. Warmth. Bathing suits. Days poolside, wasting away under the severity of the sun lambasting your back. No work in sight. You’re lying down, and it’s not the laying you’re focusing on but the down part. Flat, planar, no stress knotting your spine or fears knitting your toes, causing that arch in your back to point ever so slightly higher. Complete and utter tranquility—even just for a moment—before the flotsam and jetsam of school and work and responsibilities resurfaces, and you re-submerge into the murkier pool of quotidian life instead of the chlorinated pool of summer. And that’s how it’s supposed to be, right? The ideal breather that term time-you envisions, that childhood-you envisioned, a respite from the norm to reflect on what has passed. Or summer is a time to not do that, to spend time thinking about the thought of doing nothing at all, which in itself is doing something, doing more than what summer requires.

Yet, most Harvard students don’t experience this summer. This isn’t to say that the antithesis of this lax watercolor is the bane of all imaginable summers. It’s the opposite actually—the vast amount of interests that are pursued throughout the summer by various students are quite laudable. Studying abroad, doing research in laboratories, interning at important causes and with notable companies, cultivating their own businesses—the list extends from there. Summertime activities help to give context to what a student is interested in and will continue to pursue throughout their time here. However, the activities each student chooses to participate in—or, more appropriately, has the opportunity to participate in—can be a representation of and status symbol in the elitism omnipresent at Harvard.

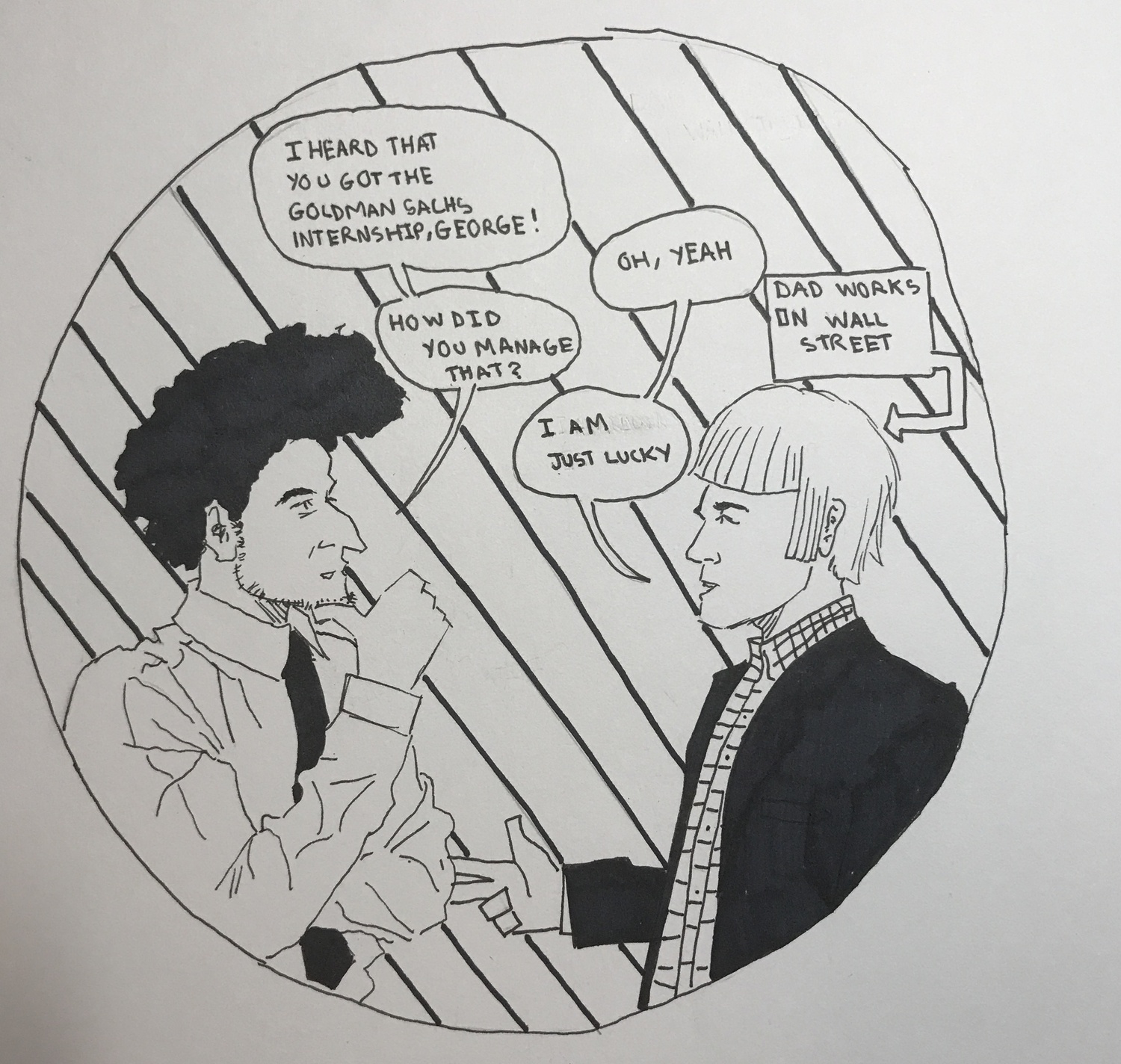

The scenario is easy to imagine because it happens so frequently. The Goldman Sachs internship snagged by the student who has a father on Wall Street, the premier lab spot secured by the student who could afford to spend the years prior to college honing their research abilities, the trips around the world taken sans financial aid by those who could afford the luxury. The connections have already been established, the networks already tethered carefully together and walked upon neatly, effortlessly, gracefully. In one smooth movement, the summer funambulist secures their experience, and the rest are left to worry if they have the right mixture of money, experience, talent, and luck to place them anywhere near the tightrope their schoolmates have already crossed.

The student who receives these opportunities isn’t necessarily the antagonist of the story here. It would be absolutely foolhardy to say that he or she does not have the capability to take on, perform well, and excel at a certain position just because they had help. However, it would be equally foolhardy not to recognize the presence of the help in the first place. Reaching the stars from a penthouse is a different story than reaching the stars from the ground.

This isn’t just another opinionated cry at the injustice of the socioeconomic hierarchy evident at Harvard. Rather, this is an acknowledgement that the injustice does not only plague students within the Harvard bubble, but follows them around the world as well. Some might say this is an unpleasant fact of life, but that idea should not warrant complacency on the part of those who bear the injustice. It should incentivize rallying, change, commentary, or at least another opinionated cry in hopes that some might combat the manifestations of socioeconomic difference at the College.

Nevertheless, these idealizations of a summer experience persevere, despite the realities of how achievable they are. Harvard students, for the large part, don’t experience this summer. These summers lie down flat but are knotted with prior connections that knit together those of privilege with privileged opportunities—the situation repetitive and depriving, year after year. It becomes difficult to undo the ties that bind these kinds of summers with inherent advantages, especially when the key to attaining these chances can lie in a network that many do not have. As such, some of these opportunities remain lost on many students—twisted, matted, and impossible to unravel.

Jessenia N. Class ’20 is a Crimson editorial editor in Quincy House. Her column appears on alternate Tuesdays.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.