News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

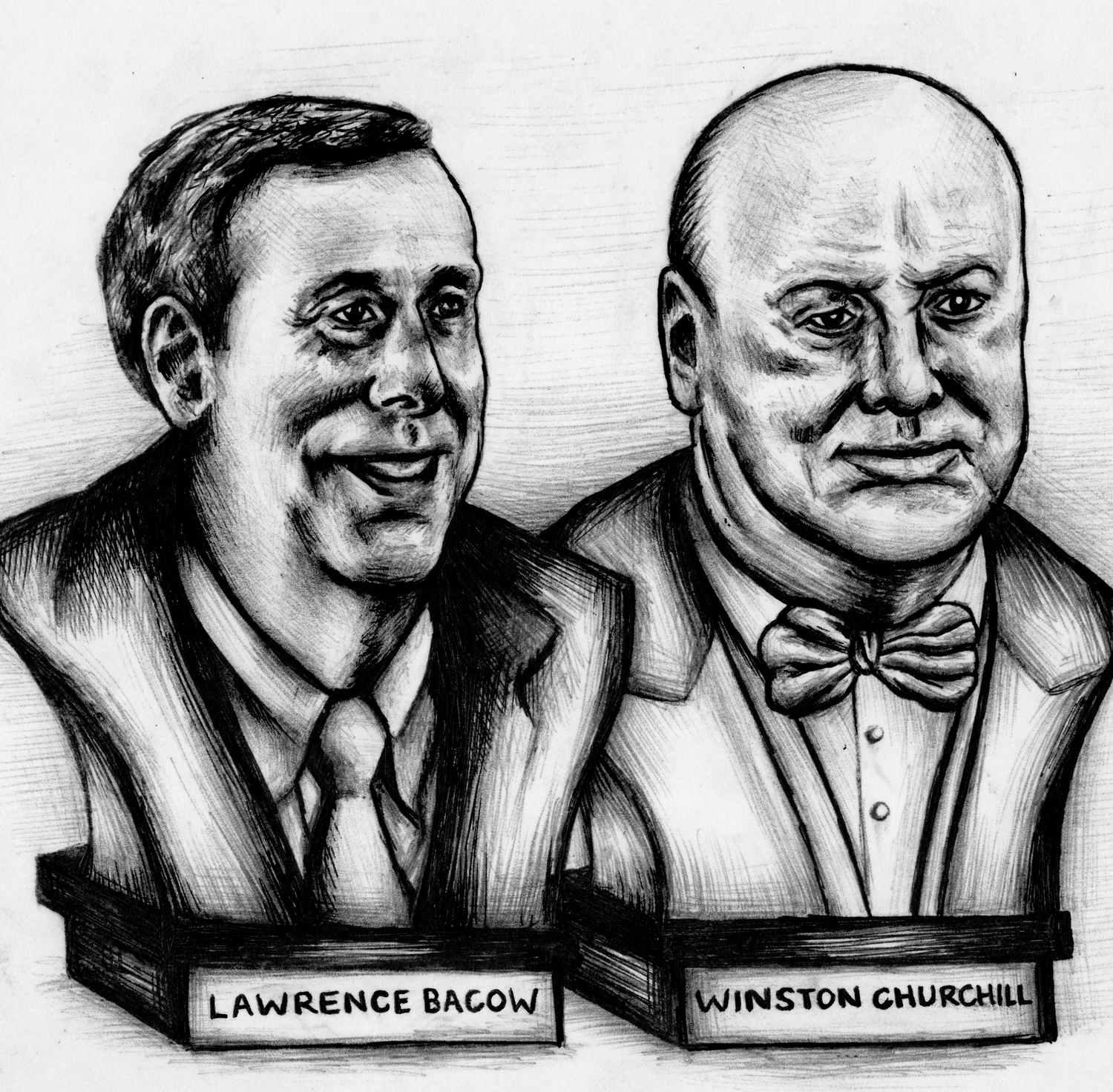

Larry Bacow and the Act of God

As we now finish our semester at home, I think it’s valuable to revisit the decision that University President Lawrence S. Bacow made two weeks ago, asking us to stay home following spring break.

In the days that followed, more of us criticized him and the Harvard administration than perhaps might have with the gift of hindsight. We decried the 5-day eviction notice; the initial confusion regarding subsidies for low-income students; the $500 one-way plane tickets that needed to be bought 48 hours before a flight; the seeming absence of consideration for international students. In the most important respect, however, President Bacow made the right decision, and it was a hard one.

Imagine you’re Larry Bacow for a moment, and the date is March 10. To situate ourselves, we can recall the timeline of what was being said about the coronavirus in the preceding weeks and days.

February 17: Dr. Anthony Fauci, a respected immunologist leading the national response to the epidemic, states that the risk for Americans of contracting the coronavirus is “just minuscule.”

March 5: The Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s public health guidance is still simply to “wash your hands.” The World Health Organization emphasizes that you should “cough into your elbow,” in a town hall a day later.

March 6: Dr. Fauci goes on national television and maintains that social distancing is not necessary, outside of the Seattle area, stating that “the overall risk in the country of being infected is low.”

March 9: After a weekend of cases, the CDC Director continues to maintain that “the risk to the American public does remain low.”

By March 9, you can see that no peer higher education institutions (with the exception of those located directly in outbreak areas) have announced a closure of campus for the rest of the semester.

The decision facing you is enormous from an institutional perspective. As the Editorial Board recalled, a former Harvard Dean of Students once remarked, “Harvard University will close only for an act of God, such as the end of the world.” There is essentially zero existing precedent, going back at least a hundred years, for a closure of more than a couple days.

Given the information available, few of us would have decided on the morning of March 10 to make the announcement to close Harvard’s campus and so abruptly at that.

Former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill told us that “it is always wise to look ahead, but difficult to look further than you can see.” In the hour of action, President Bacow looked ahead and saw what even many national health officials did not see.

In the days that followed, public health experts came out in support of Bacow’s decision. As Marc Lipsitch of the School of Public Health observed to The Crimson afterward, “we were some days or weeks away from having a really big problem on our hands, and the only thing we can do to slow it down is to … be in places other than dorms.” Kenneth McIntosh ’58 of Harvard Medical School agreed that it was “better to do something that makes epidemiologic sense at this point than to wait.” Every additional day, in hindsight, would have brought increasing risks.

These risks would have been dangerous for Harvard professors — a recent profile pegged the average age of the tenured Faculty of Arts and Sciences faculty at 56, with 25 percent over the age of 65 — and for students with pre-existing conditions. Reducing the density on campus was, quite literally, a matter of life and death.

Harvard turned out to be one of the leaders in making the decision. MIT announced hours later. A week later, the entire Ivy League had followed suit, as had universities across the country.

So what about the criticism? In a perfect world, the administration would not have initially issued guidance telling students to stay on campus for spring break; many took this as a directive to cancel their plane tickets home, which they later had to rebook.

But it’s important to remember how fast things changed. When he realized the first decision was wrong, Bacow rightly and quickly reversed course. He recognized that two wrong decisions didn’t make a right. We should be very glad that he didn’t give us the option of moving out at the end of spring break — which would have come when Massachusetts was nearing 1,000 confirmed cases and beginning a stay-at-home advisory. The five-day eviction notice, in the end, served a purpose: to get people off of campus and away from the danger of dormitory-based transmission, as quickly as possible.

The late Zell Miller, the former Georgia governor, liked to tell a story about his relationship with Jimmy Carter, the U.S. president-turned-humanitarian. Miller, who did not adhere to party lines as rigidly as Carter would have liked, once joked that half the personal notes he’d received from Carter “are giving me hell and half are bragging on me.” But, he said, “I figure I’m doing OK batting 0.500 with Jimmy Carter.”

In half the decisions that Bacow faced in this extraordinary episode, he may have made mistakes — just as we might have in the same position. But those mistakes (several of which were later corrected) came on logistics and nothing more. On the half that really mattered — the decisions about how best to protect Harvard and the lives of its faculty and students — he overwhelmingly rose to the occasion. For that, we all owe him a debt of gratitude. After all, it’s not easy batting 0.500 with God.

Andrew W. Liang ’21, a Crimson Editorial editor, is a Social Studies concentrator in Adams House. His column appears on alternate Thursdays.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.