News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

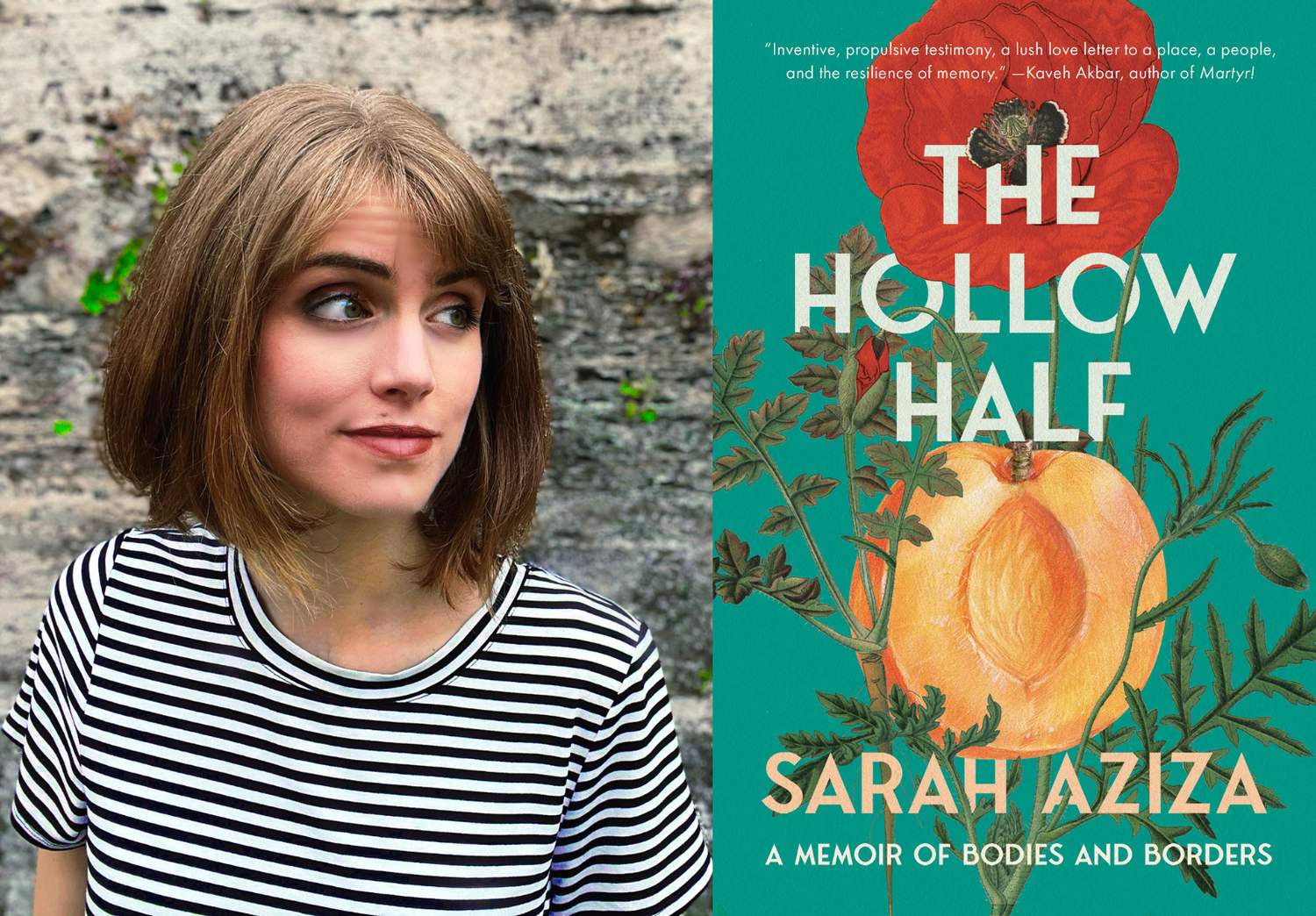

Author Profile: Sarah Aziza on Crisis Reporting and the Music of the Book

Seven-year-old Sarah Aziza was notorious at her local library for bringing a crate every week and filling it to the brim with books before she left. Aziza is now a published author, journalist, and poet featured in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, Best American Essays, Harper’s Magazine, The Washington Post, and The Guardian, among other publications.

As the daughter of a Palestinian refugee father, books and oral storytelling are an important way for Aziza to hold onto her past and understand new sides of her family members. Aziza’s genre-bending debut memoir, “The Hollow Half,” draws from her background in crisis reporting as well as personal stories spanning three generations to explore displacement, erasure, and nation-building.

Aziza has received numerous grants from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, but a career in writing was not what she expected to do with her life. After her undergraduate degree at the University of Pennsylvania, Aziza won a Fulbright to teach college-age students through the United Nations Relief and Works Agency in Jordan.

“I was reluctant to step out of my interest in current affairs, policy, things happening on the ground,” Aziza said in an interview with The Crimson. “MFAs didn’t really interest me. I didn’t want to sequester in the way that I felt an MFA might sequester me.”

After her work in Jordan, Aziza was accepted to the long form journalism program at New York University. Her years of experience in crisis reporting honed her editorial skills and acted as a bootcamp in streamlining her prose.

“Editorially, it was really helpful because I was drawn secretly to more creative writing. I think that journalism was a really good bootcamp in being really rigorous with myself, as far as streamlining my prose, becoming less precious about my adjectives and about my flowery language,” Aziza said.

Aziza’s first drafts were usually elliptical, experimental, or indulgent. Her editors would then ruthlessly strip her writing down to help her “kill her darlings,” a technique in creative writing where the writer removes bits of prose that are beautiful in and of themselves, but do not contribute to the overall piece.

“I’m still not interested in sequestering. I’m not interested in just getting lost in my own thoughts and just polishing sentences in a corner,” Aziza said. “I think that my horizontality and interest in the moving, living world carries over into whatever I’m doing.”

Aziza’s debut memoir “The Hollow Half” took on a life of its own before Aziza set the intention to write a book.

“I think that a lot of things in my life, I’ve been afraid to fully claim until I had one foot in it. So, I was recently discharged from the hospital,” Aziza said. “I’d actually decided to give up even journalism at that point, just because of the way that my experience in the hospital left me feeling really humiliated and distrustful of my own mind.”

Then, in February and March of 2020, Aziza began to have a series of dreams.

“I found myself really needing to process through writing, sort of like journaling almost, but even in more of a fugue stage, just waking up from these dreams that were really like recurring memories and just writing them down as a way to process,” Aziza said.

As the dreams began to compound, Aziza realized how much she didn’t know about her family, specifically her grandmother, who was the subject of most of the dreams. She began to ask her father more questions.

“I’d grown up in a Palestinian family. I knew the contours of our history, but I never thought really deliberately about how certain points in our history intersected with my family members’ lives,” Aziza said. “I started to pick up more historical texts and start to plot out parts of her life, features of her personality, stories that she would tell, and map them onto the macro story of her multiple displacements.”

Aziza looked into her father’s life as well, and how U.S. foreign policy intersected with her family’s lives. She poured through declassified Cold War documents and Palestinian literature alike.

“As a form of sustenance, and even maybe coping with all of the trauma I was dredging up, I was reaching for our writers,” Aziza said.

Aziza began to experiment with found materials, including her medical records, snippets of which are featured in “The Hollow Half.”

“There’s so much jargon, and it’s like another representation of how the body can be documented, but sort of lost in a particular type of language.”

On a socially distanced walk in the park during the pandemic, Aziza’s friend said that it sounded like Aziza was writing a book.

“And that was a confrontation for me with the fact that that’s maybe the biggest dream I didn’t know I had,” Aziza said.

Aziza’s childhood bookshelves were full of hand-me-down copies of Thomas Hardy, the Brontës, and Shakespeare, gifted by other expats.

“Being an expat, a third culture kid moving around and being a little out of place all the time, books were really my shelter. Books to me were sacred objects,” Aziza said.

When Aziza read “The God of Small Things” by Arundhati Roy, she experienced a true portal to another world that captured Roy’s experiences with the caste system in India.

“The music of the book was so different than anything I’d experienced. So there was something unlocked in me when I read that,” Aziza said. “That writing can actually be magic. It’s not just the enchanting, engrossing, compelling prose of a Jane Austen or Thomas Hardy, but it can actually be magic.”

When Aziza’s friend encouraged to compile her research as a book, Aziza’s first reaction was fear.

“The amount of fear that I felt when she said it sort of told the truth. It revealed to me, ‘Hey, this is something you really want. And the recognition is what is scaring you the most,’” Aziza said.

Her book was published four years later.

—Staff writer Laura B. Martens can be reached at laura.martens@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.