News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

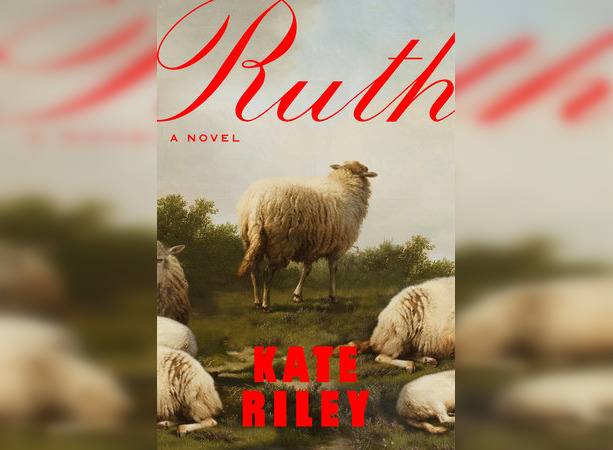

‘Ruth’ Review: A Ruthless Critique of Kate Riley’s Christian Communist Novel

3 Stars

In the Christian-commune world of Kate Riley’s “Ruth,” dolls are banned and the Bible is the only acceptable children’s reading, revered above all else. Clothing is devoid of color and everyone’s diet is the same, so that all the men “look like Abraham Lincoln” and the women like “rats in kerchiefs.” Food is a communal good. Women exist only to serve their husbands and children to learn to serve God.

It is not an environment designed to encourage curiosity about the outside world, which is unfortunate for the novel’s eponymous main character, Ruth, who battles a particularly strong case of it. What do people of other races look like? Is the distant land of Zanzibar as fantastical as she dreams? What is it like to kiss a boy? All these are questions Ruth, a child with a penchant for knowledge, illicitly ponders.

In “Ruth,” Kate Riley, herself raised in such a commune, displays her masterful and nuanced worldbuilding. The detail with which she describes the commune is meticulous and clever, heightening the reader’s frustration along with Ruth’s as they contend with the suffocating restrictions of this world.

But the extensive worldbuilding is to the detriment of Riley’s main character, whose development Riley neglects as a result. Ruth’s initial struggle with her curiosity is fertile soil for a powerful narrative arc, but sadly from that soil emerges little more than a sprout; Riley appears to have forgotten that narrative hinges just as much on the characters as the setting in which they operate.

Riley seems to set herself up for success with her initial characterization of Ruth, as a girl just as guilty for feeling curious as she is curious. When Ruth learns that people outside the commune live in locked houses and own their own goods, each question leads to even more. To satisfy her curiosity, Ruth turns to literature, but books only inflame it further, as she wonders about distant lands and ponders racial issues in the United States.

Aware of her grave sin in imagining life outside the commune, Ruth suppresses her wonder — in matters both big and small. When a classmate remarks that another girl’s maroon dress, not conservative enough for the commune, is “becoming,” Ruth agrees internally, but is so timid that she will not dare voice it. She is “dutiful” outwardly, but also inwardly, not admitting even to herself how unfair she finds the commune’s restrictions. “Remember to remember to remember,” she commands herself.

One might assume that Ruth will eventually break free of the commune’s restrictions, given her propensity for knowledge-seeking, diametrically opposed with the objectives of the commune. Indeed, Riley leads the reader to believe she is fomenting this insurrection in her character’s psyche. “Ruth is clever enough to misunderstand all that she does not like,” Riley writes. Is Ruth a sly rebel in the making?

Riley needs to make up her mind eventually on this question, and she never quite does. The reader hoping for this insurrection will be left disappointed, as that long deferred rebellious transformation never manifests and Ruth remains confined to the state of subservience the reader first found her in. This deeply unsatisfying pacing is a flaw in what would otherwise be a beautifully-constructed novel.

Why is Ruth, three quarters into the novel, still caught in the same maddening, half-hearted dance with her subconscious? As she wishes ill upon another member of the commune she asks herself, “Should she suppress such prayers? Did they harm anyone but herself?” Such insecurity may have been acceptable 100 pages ago. But Ruth is no longer a little girl and this is no longer the early stage of a novel; there is little patience left for such spinelessness in the main character in whom the author has invested so much hope.

Detailed and astounding though Riley’s worldbuilding power may be, it cannot compensate for the meager development of the character who gives the book its name.

—Staff writer Alexandra M. Kluzak can be reached at alexandra.kluzak@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.