News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

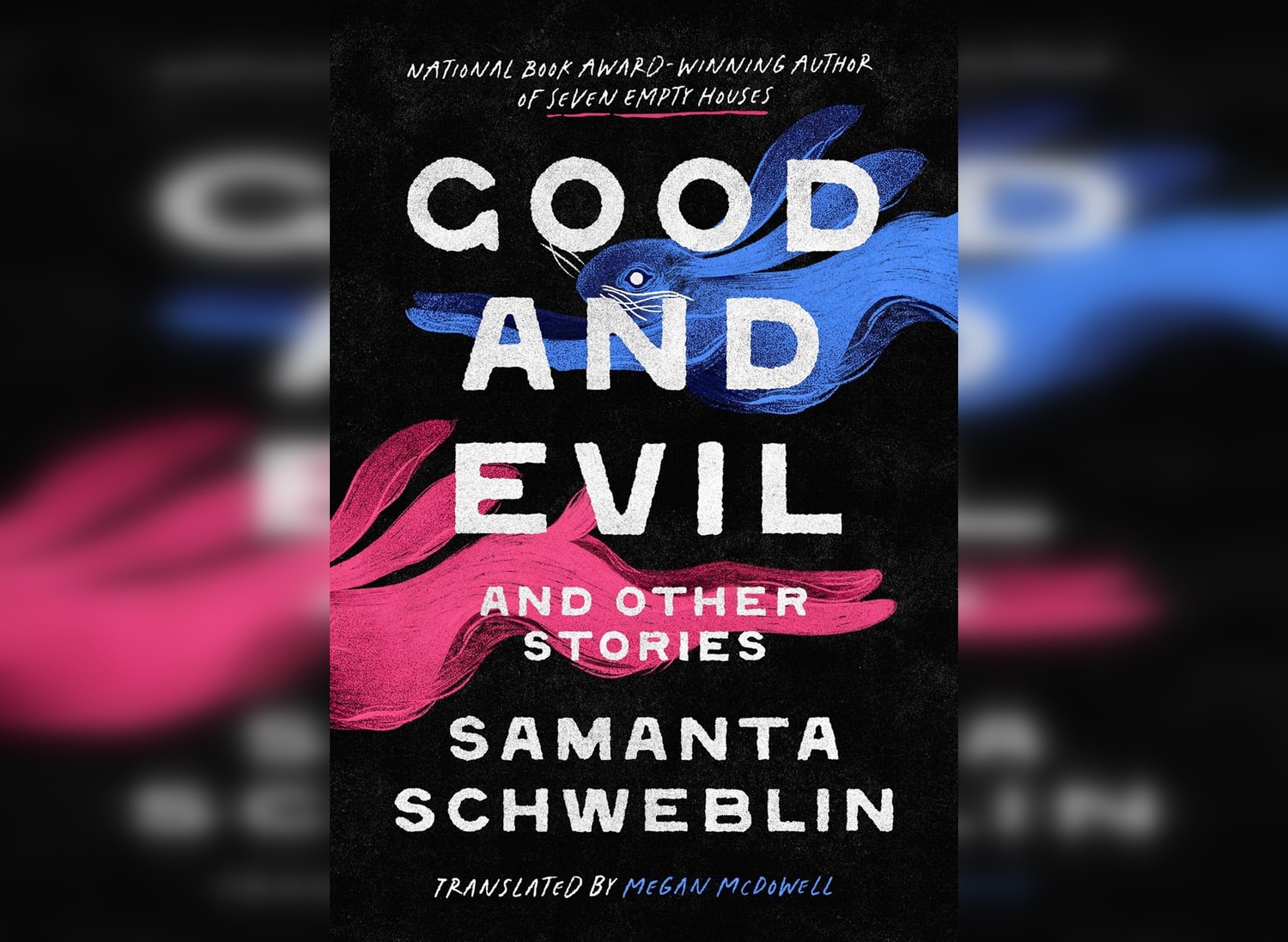

‘Good and Evil and Other Stories’ Review: A Sextet of Living and Losing

4.5 Stars

Content warning: The following book review includes brief mentions of suicide and other sensitive topics.

Samanta Schweblin knows how to spook. The Argentine author’s newest short story collection, “Good and Evil and Other Stories,” translated by Megan McDowell, is impressive. In just six stories, Schweblin demonstrates a mastery of evocative narration and chilling insinuation. The tales are not clearly connected yet inhabit the same dark, surrealist territory that is human imagination. What the stories leave unsaid proves to be the most disturbing of all, inflicting an unnerving freedom on readers’ minds and emotions.

The title of “Good and Evil and Other Stories” severely understates the range showcased by the book. Although the title suggests that clear, simple binaries will guide the narratives, there are no such delineations. Death stars in all six stories, as do family and matriarchal relationships. One mother tries to drown herself in the lake behind her family’s home. Another seeks her deceased son in the form of a horse. A poisoned cat haunts its former owner. A father-mother-son trio is shattered after an incident renders the son mute. A young girl becomes an only child. And finally, a bizarre confrontation convinces a mother to let go of her long-lost daughter.

Together, these six stories highlight Schweblin’s wield of tension as a potent narrative tool. McDowell’s translation skillfully maintains this grip. For example, in “Welcome to the Club,” a mother cannot ignore the call of the lake in which she tried drowning herself. To keep herself alive, she clings to the guilt she would feel were she to abandon her daughters. The end of the story implies this guilt may not be enough, marking the first of many ominous final words.

Similarly, in “A Fabulous Animal,” the author wastes no time in establishing “the accident” as a critical breaking point in one woman’s life, motherhood, and friendships. The nature of this accident is withheld until the end of the story, gripping the reader in suspense as they piece events together from the fragmented narration.

The fourth story in the collection, “An Eye in the Throat,” is a particular standout. After a young boy receives a tracheostomy, his inability to speak severs his bond with his father. Soon, the father starts receiving nightly phone calls in which nobody speaks. He becomes obsessed with reaching the mysterious caller, casting aside his family, work, and responsibilities. In this cruel juxtaposition of silent calls and a silenced son, the father’s desperation for someone to pick up the phone is symbolic of his desperation for communication with his son. Schweblin’s writing is subtle and deft; the author does not force this realization on readers but rather lets them discover the sheer tragedy of the symbolism for themselves. Lighting the way are unsettling questions from the young boy, who thinks, “Sleeping is dangerous. If I choke, I wake up. But what is it, really, that chokes me?”

While tension dominates much of the book, Schweblin successfully balances it with release. The pacing of “Good and Evil and Other Stories” is just right. Each story begins in media res and avoids extraneous description that would eat up precious pages. The author also provides enough world-building and ambiguity for the stories to live on, far beyond what is written and read. Of course, a short-form story collection may offer greater flexibility for organization than a full-fledged novel. However, the challenge of deciding the relative lengths and ordering of each story is not to be underestimated.

Stories of varying lengths comprise a diverse yet cohesive collection. The six works feature different points of view and narration styles, from scatterbrained first-person to cool and meticulous third-person, which effectively bring unique characters to life. These changes in perspective ensure that the book does not rely upon a single voice. At the same time, common themes of mortality, fear, and desire weave throughout the sextet, guiding the reader from one world to the next seamlessly.

In addition to varying length, Schweblin varies the relationship dynamics between characters. Not all of the characters are equally convincing; the “chief” in “A Visit From the Chief,” for instance, is somewhat one-dimensional. Likewise, some of the stories are less striking than others. “William in the Window” is a humorous ghost story but does not feel as fresh as its siblings. Nonetheless, the collection in its entirety stands strong and offers substance for every audience.

Alongside Schweblin’s previous award-winning works, such as “Fever Dream” (2014) and “Seven Empty Houses” (2015), “Good and Evil and Other Stories” sets the bar high. The collection is a compelling exhibition of tension and contrast as narrative elements. Much is left to the imagination, which magnifies the emotional pummeling of the book by its own accord. As they await Schweblin’s next publication, readers may carry on these stories’ mission to probe the disturbing, the sinister, and most of all, the human.

—Staff writer Audrey H. Limb can be reached at audrey.limb@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.