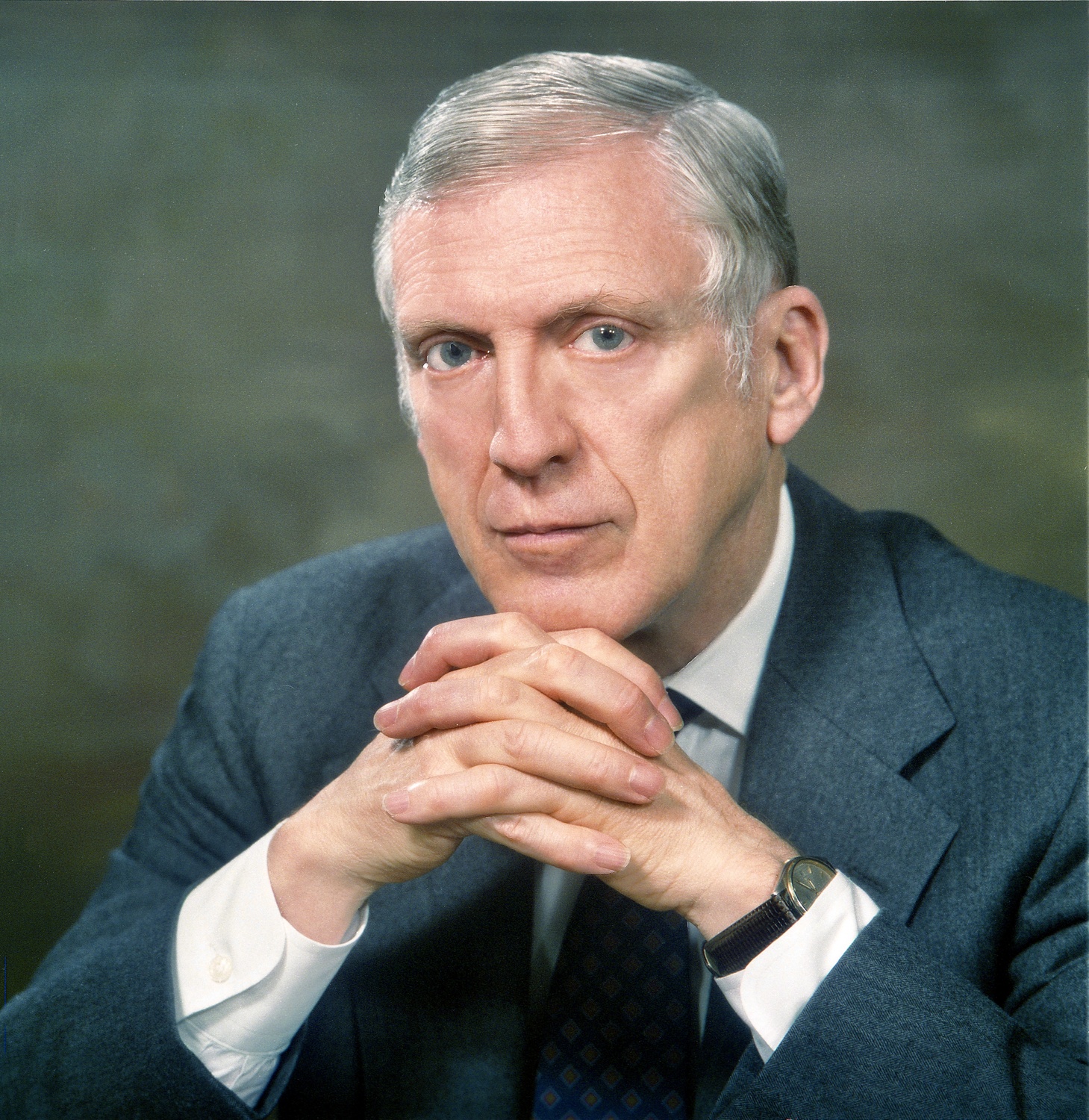

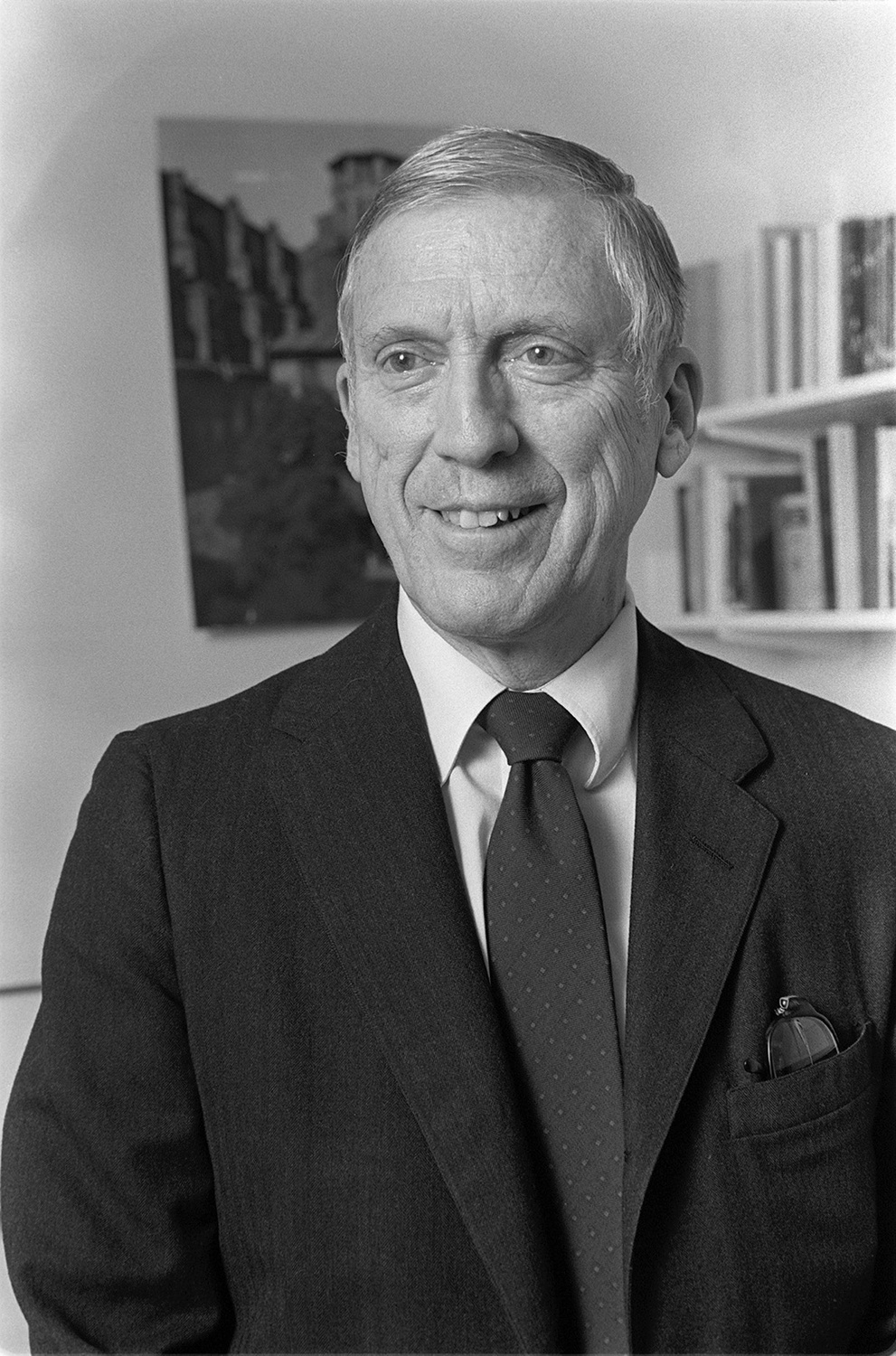

Harvard Professor Thomas Bisson, ‘Exceptional’ Medievalist, Remembered for Dedication to Scholarship

Thomas N. Bisson, a professor emeritus in medieval history at Harvard, died on June 28 at the age of 94. His family and colleagues remembered him as a meticulous scholar with an eye for his subjects’ humanity, and as a “caring presence” in students’ lives.

Sometimes, incoming Harvard students with no particular academic interest in medieval studies would sign up for a freshman seminar with medieval history professor Thomas N. Bisson. He would change their minds.

“He inspired students who would come to Harvard thinking, I’m going to concentrate in, I don’t know, Economics, Gov, wherever,” said his daughter, Noël Bisson, who is dean for academic programs at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. “And they would take his freshman seminar, and it just blew their minds.”

Bisson, a professor emeritus since his retirement in 2005, died on June 28 at the age of 94 following a brief illness.

Bisson first taught at Harvard as a visiting professor in 1986 and officially joined the faculty in 1988. He previously held a position at the history department at the University of California, Berkeley, where he taught for two decades. Bisson graduated from Haverford College in 1953 and obtained his Ph.D. from Princeton University five years later.

During his Harvard career, Bisson served as chair of the History department and the Standing Committee on Medieval Studies. He was also president of the Medieval Academy of America.

Bisson was described by his two daughters, Noël and her sister Susan Bisson Lambert, as “an exceptional and admired teacher” in the obituary they wrote in his memory, adding that he “shaped his students as historians and remained a deeply caring presence as they pursued diverse paths.”

“Those who studied with Bisson felt a common bond that crossed institutional lines,” they added.

Bisson was also a key figure in the lives of several faculty members, including Romance Languages and Literatures professor emerita Virginie Greene, who arrived on campus as an assistant professor in 1998.

“He was one of the senior colleagues who helped me to feel I belonged and I was included,” Greene wrote in a statement to The Crimson.

She fondly remembered being hosted by Bisson and his wife Carroll at their home, both for the occasional dinner, as well as a gathering where she was introduced to “medievalists of all ranks and ages” — and to haggis, a Scottish dish traditionally cooked in a sheep’s stomach.

Bisson’s work focused mainly on medieval France and Catalonia, and he has published several works in his field, including the first complete English translation of Robert of Torigni’s Chronographia.

Greene recalled conversations with Bisson about his 1998 book, Tormented Voices, about 12th century Catalonia.

“He had been touched humanly by what he had found in obscure medieval documents: echoes of oppression, suffering, and resistance from people whose voices and concerns are rarely recorded (in this case, peasants of Catalonia),” Green wrote.

According to Bisson, her father continued his work long after his retirement, publishing his last book at age 90.

“He was working and writing articles into his nineties,” Bisson said. “So really an active scholar for his whole life.”

English professor W. James Simpson knew Bisson through the Committee for Medieval Studies, and wrote that their interactions were “marked by his measure, by his courtesy and by his evident care for scholarly truth and rigor.”

“I admired and liked him tremendously,” Simpson wrote.

Greene wrote that Bisson will continue to make an impact through his contributions to academia.

“Tom’s work was and still is relevant to our times,” Green wrote. “As a scholar, he incarnated for me American academia at its very best: cosmopolitan and proud of its own American culture, attentive to details and able to address large issues, relaxed and disciplined.”

“I am privileged to have crossed paths with him,” Greene added.

Bisson was also passionate about classical music and baseball, and was “as happy to discuss Koufax as Schubert,” according to his daughters.

“I have vivid childhood memories of my dad playing the piano at night,” Noël Bisson wrote in an email. “Music was in our house all my life. It’s no wonder that both my sister and I became musicians, and my dad’s grandchildren are pursuing careers in the performing arts.”

“Beloved by all,” in his daughters’ words, Bisson is remembered by faculty and students alike for his academic and personal impact.

“That’s kind of the legacy of impact that my father had in terms of people who aren’t professional medieval historians, but who whose lives were changed by working with him,” Noël Bisson said.

—Staff writer Megan L. Blonigen can be reached at megan.blonigen@thecrimson.com. Follow her on X at @MeganBlonigen.

—Staff writer Caroline G. Hennigan can be reached at caroline.hennigan@thecrimson.com. Follow her on X @cghennigan.