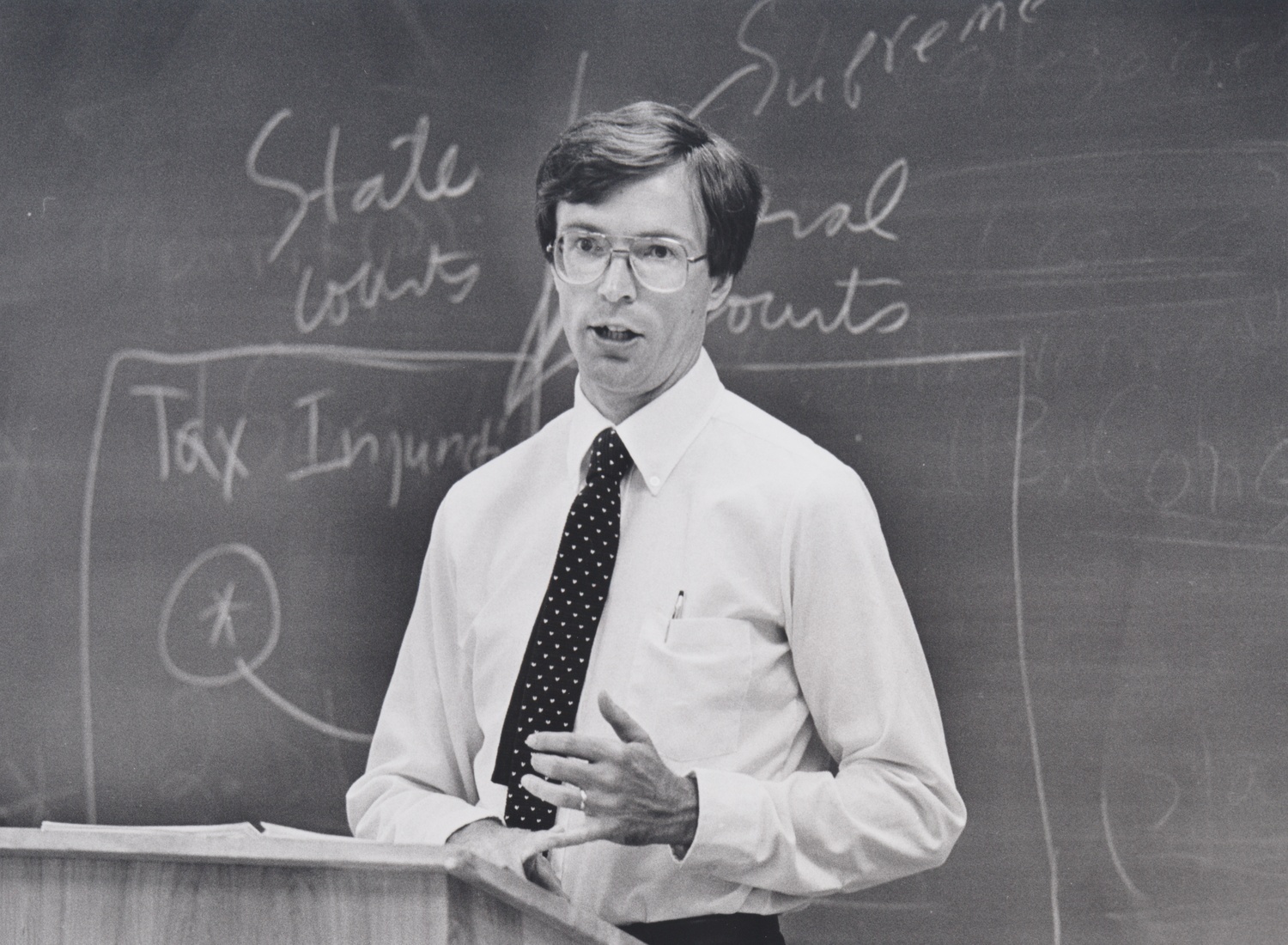

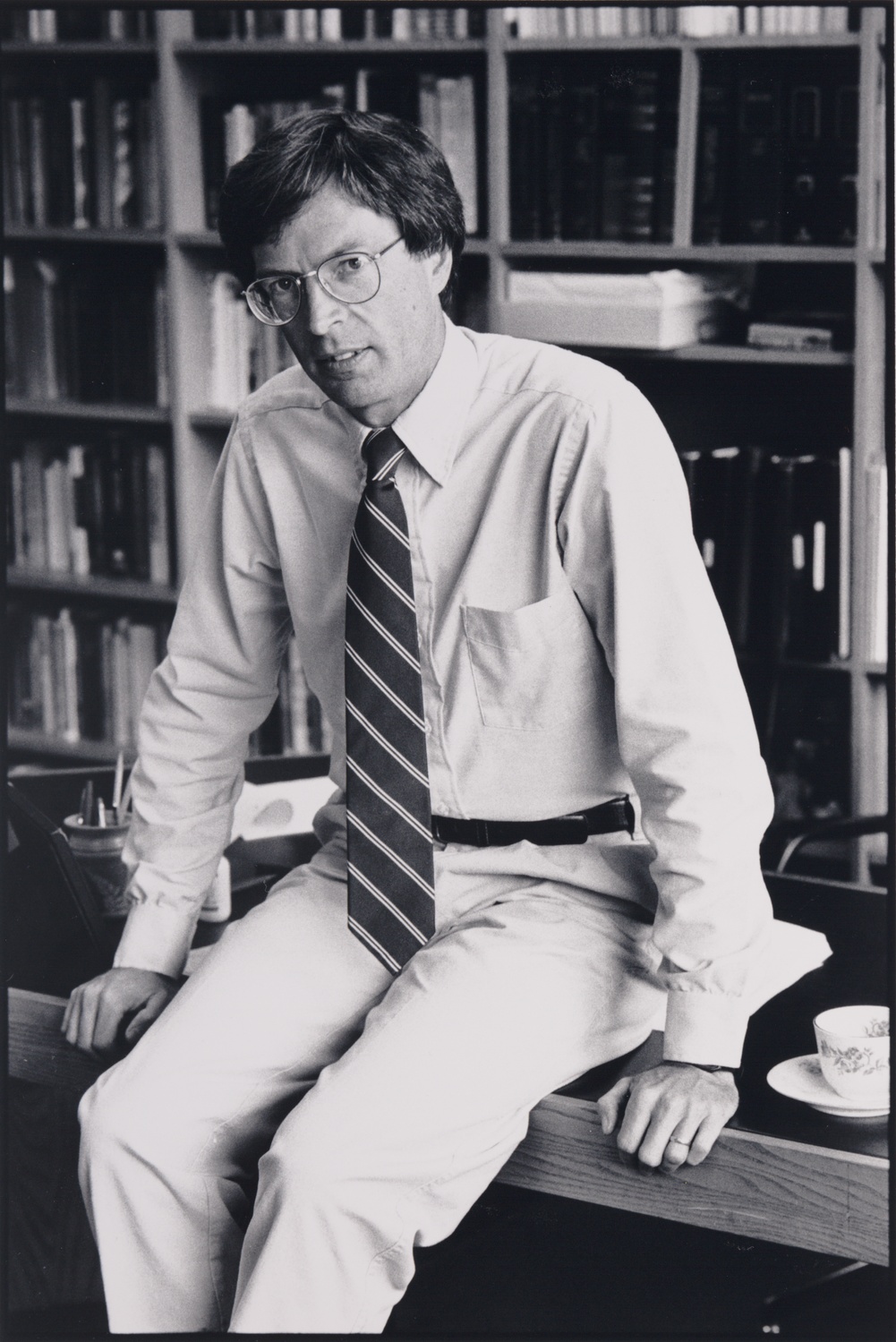

Harvard Law School Professor Richard Fallon Remembered as Lucid Scholar, Committed Instructor

Harvard Law School professor Richard H. Fallon Jr. died earlier this month at age 73. His students and colleagues remembered him as a clear-eyed scholar, dedicated to students and possessed of a quiet but ready wit.

When Harvard Law School professor Richard H. Fallon Jr. attended a small conference in New York a decade ago, he was surrounded by venerable legal scholars. But after watching a graduate student present a paper that piqued his interest, Fallon stepped aside to introduce himself to the student.

A renowned legal scholar in his own right, Fallon discussed the paper extensively with the student, Daniel S. Francis, who had just presented at his first legal conference. And what started as a conversation quickly became a lifelong mentorship from Fallon, who helped Francis find his footing in the opaque world of legal academia.

“It’s hard to think of a better anecdote than the fact that 10 years ago, at a conference full of leading scholars with fancy job titles, Dick made time to introduce himself and provide support and encouragement to a pretty random grad student,” said Francis, now an assistant professor at New York University Law School.

“That, for me, just encapsulates his energy in giving kindness to everybody he crossed paths with,” he added.

For an academic renowned worldwide for his insightful scholarship across multiple fields of legal inquiry, Fallon’s disarming humility and dauntless commitment to his students made him unique, his former colleagues and students said.

Fallon, a leading scholar of constitutional law and federal courts who was beloved for his tireless devotion to raising the next generation of legal experts, died on July 13. He was diagnosed with “an aggressive cancer” earlier this summer, according to an email from HLS Dean John C.P. Goldberg to Law School affiliates. Fallon was 73.

‘An Academic’s Academic’

When University Professor Lawrence H. Tribe interviewed Fallon for an assistant professor position at HLS in 1981, he was immediately taken by Fallon’s deep understanding of constitutional law scholarship.

“He struck me as very open-minded, very steeped in actual scholarship, rather than kind of secondhand, simplistic slogans,” said Tribe, a star constitutional law scholar. “I was very impressed.”

A lifelong academic, Fallon spent his whole scholarly career studying and teaching at some of the top universities in the world.

He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1974 in history from Yale University, where he served as managing editor of the Yale Daily News. Fallon then went to Oxford University on a Rhodes Scholarship. Across the pond, he earned a second bachelor’s degree in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics and then returned stateside to attend Yale Law School, where he earned a J.D. in 1980.

Before becoming a professor, Fallon clerked for Judge J. Skelly Wright of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit and Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. of the Supreme Court. He became an assistant professor in 1982 at HLS, and earned tenure just five years later. Fallon would go on to spend his entire teaching career at the Law School.

Colleagues said Fallon was a remarkably clear thinker with a thorough approach to scholarship. He was also remarkably generous to opposing views, with multiple peers saying his papers would flesh out — accurately and in detail — the arguments he disagreed with before refuting them.

Fallon wrote extensive comments to everyone from former students to colleagues in the field. Curtis A. Bradley Jr., a University of Chicago Law School professor who studied under Fallon, said Fallon gave him comments on his first paper that were both “very encouraging” and “critical in a helpful way.”

“He was very generous and very kind in his comments. But also, you know, he would tell you the truth and he would give you critical feedback that was helpful,” Bradley said.

Fallon’s scholarship was prolific and wide-ranging. He often focused on questions about how the Constitution should be interpreted and the laws governing federal courts, especially the Supreme Court.

In one paper, Fallon argued against strictly following originalism, a theory of legal interpretation that advocates understanding the Constitution as it was read when it was adopted. In another, Fallon discussed why we should be skeptical of amicus briefs by law professors.

Fallon also edited the 7th edition of Hart and Wechsler’s “The Federal Courts and the Federal System,” the authoritative text on federal court law. Another book of his discussed the legitimacy of the Supreme Court.

Many of Fallon’s articles addressed subjects that now provoke heated debate in American politics. The Supreme Court’s legitimacy has come under growing scrutiny amid a run of controversial rulings made by the court’s conservative majority. Many such decisions — from ending the federal right to an abortion to eliminating lower courts’ ability to issue nationwide preliminary injunctions — used the lens of originalism.

In 2021, Fallon was nominated to the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court of the United States. The committee, established by then-President Joe Biden, was tasked with investigating possible reforms to the Supreme Court.

Fallon, his colleagues and former students said, had a remarkable ability to break down contentious topics without wading into ideology that might color his analysis one way or another.

“He had a knack for writing on really foundational questions in a way that people from a wide range of ideological perspectives would find value,” said Orin Kerr, a Stanford Law School professor who took Fallon’s course on federal court law.

“He was an academic’s academic in really trying to work through these hard questions,” Kerr added.

Despite his towering intellect, Fallon was known to be open about lingering uncertainties he harbored and remarkably generous — in his conversations and scholarly writings — to any opinions that might oppose his own.

“Richard Fallon’s work was of the highest quality. It was intellectually rigorous and incredibly fair to the positions with which he was disagreeing, which was oftentimes my position,” said Randy E. Barnett, a Georgetown Law School professor who knew Fallon professionally.

“He was the epitome, really, of what a legal scholar should be,” Barnett added.

‘Wickedly Funny’

Over the more than four decades former HLS Dean Martha L. Minow knew Fallon, the two exchanged countless article and book drafts full of complex legal arguments. But one day, Fallon shyly told Minow that he had written a different kind of publication: a novel.

Fallon had authored a political satire, “Stubborn as a Mule,” that poked fun at the blind worship of free markets, the politically correct nature of academia, and sensationalizing journalism. The story was set in Maine, his home state and the location of his family’s vacation home.

Minow, who knew Fallon since they were classmates at Yale Law School, called the book “wickedly funny.”

“He’s very funny and quietly funny,” Minow said, adding that the novel “was the most public presentation of something that those of us who know him personally always have seen: that he’s got a great sense of humor.”

Former colleagues and students agreed that Fallon possessed a clever sense of humor that could get anyone chuckling.

“From the beginning, it was clear he had a kind of very wry, self-deprecating wit,” said Tribe, the University professor. “He was somebody who had a twinkle in his eye, often accompanied by pretty hilarious stories.”

That lightheartedness even came out in Fallon’s classroom.

At Harvard College, Louisa Susannah “Lulu” Chua-Rubenfeld ’18 took Fallon’s undergraduate freshman seminar on the history of the Supreme Court. She remembered when Fallon walked into class, most days he would playfully trip over a trash can in the classroom.

“Without fail, he would trip over this blue trash can and just look so bashful, and he had a very wry sense of humor about it,” Chua-Rubenfeld said.

“He almost looks like one of those floppy balloon figures outside of car dealerships,” she added. “He’s a very tall, lanky man, and he would always make us laugh.”

A ‘Gifted’ Mentor and Teacher

When New York University Law School professor Rachel E. Barkow enrolled at Harvard Law School, she found herself intimidated by the sharp students and revered faculty members that surrounded her.

“I was a very shy, insecure law student, and everybody at Harvard Law School seemed to be boasting about their brilliance,” Barkow said.

Then she met Richard Fallon.

Barkow was just as impressed by Fallon’s intellect. But unlike many of her peers and other instructors, Barkow said, Fallon was approachable and remarkably generous with the time he spent supporting students.

“He was this amazing professor who was as brilliant as everybody else, but so humble and so kind,” Barkow said. “I just immediately gravitated toward him because he was just so nice and normal.”

Barkow took his class on administrative law. Then she worked as his research assistant supporting his work editing Hart and Wechsler’s “The Federal Courts and the Federal System.” When she later clerked for a judge and became a professor, Fallon wrote her letters of recommendation.

For Barkow, Fallon became a lifelong mentor. And she was not alone.

Many former students said they took one class with Fallon or had one conversation with him at a conference, and found themselves with a long-term guide who helped guide them throughout their careers and support their work for decades to come.

Fallon, they said, possessed an apparently endless generosity and eagerness to pour time into supporting his students — even undergraduates with limited backgrounds in legal studies.

Gabriella A. Mestre ’23 took Fallon’s popular undergraduate course, Government 1510: “American Constitutional Law.” In one instance, she remembered, Fallon had a conflict come up with a planned two-hour-long review session — a sick family member or a lost voice, Mestre said — that would usually mean canceling the meeting.

But even when his students told him to reschedule the meeting, Fallon said he would stick with the in-person session. Then he hosted two more Zoom sessions later when some were still left confused by the complex materials.

“A lot of the professors are really great and kind, but I just feel like that’s not the norm — to just go above and beyond trying to make everybody understand the subject,” said Metre, who decided to apply to and ultimately attend HLS because of Fallon.

Fallon was also able to explain complex legal subjects with what Minow called a “gift of clarity.” Barkow said that as a student taking his administrative law course, she could understand even the most convoluted topics when Fallon broke them down.

“It’s just this amazing ability to be clear at the same time you’re explaining something that is inherently complicated and complex,” she said.

Fallon was twice awarded the Law School’s Sacks-Freund Award, which honors excellence in teaching.

Harvard Kennedy School professor Maya Sen ’00, who was a teaching assistant for Fallon’s undergraduate course, called Fallon “one of the most gifted lecturers” at the College.

“It’s such a huge loss for the College. There’s no one who can really fill those shoes,” she said.

—Staff writer Caroline G. Hennigan can be reached at caroline.hennigan@thecrimson.com. Follow her on X @cghennigan.

—Staff writer William C. Mao can be reached at william.mao@thecrimson.com. Follow him on X @williamcmao.