News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

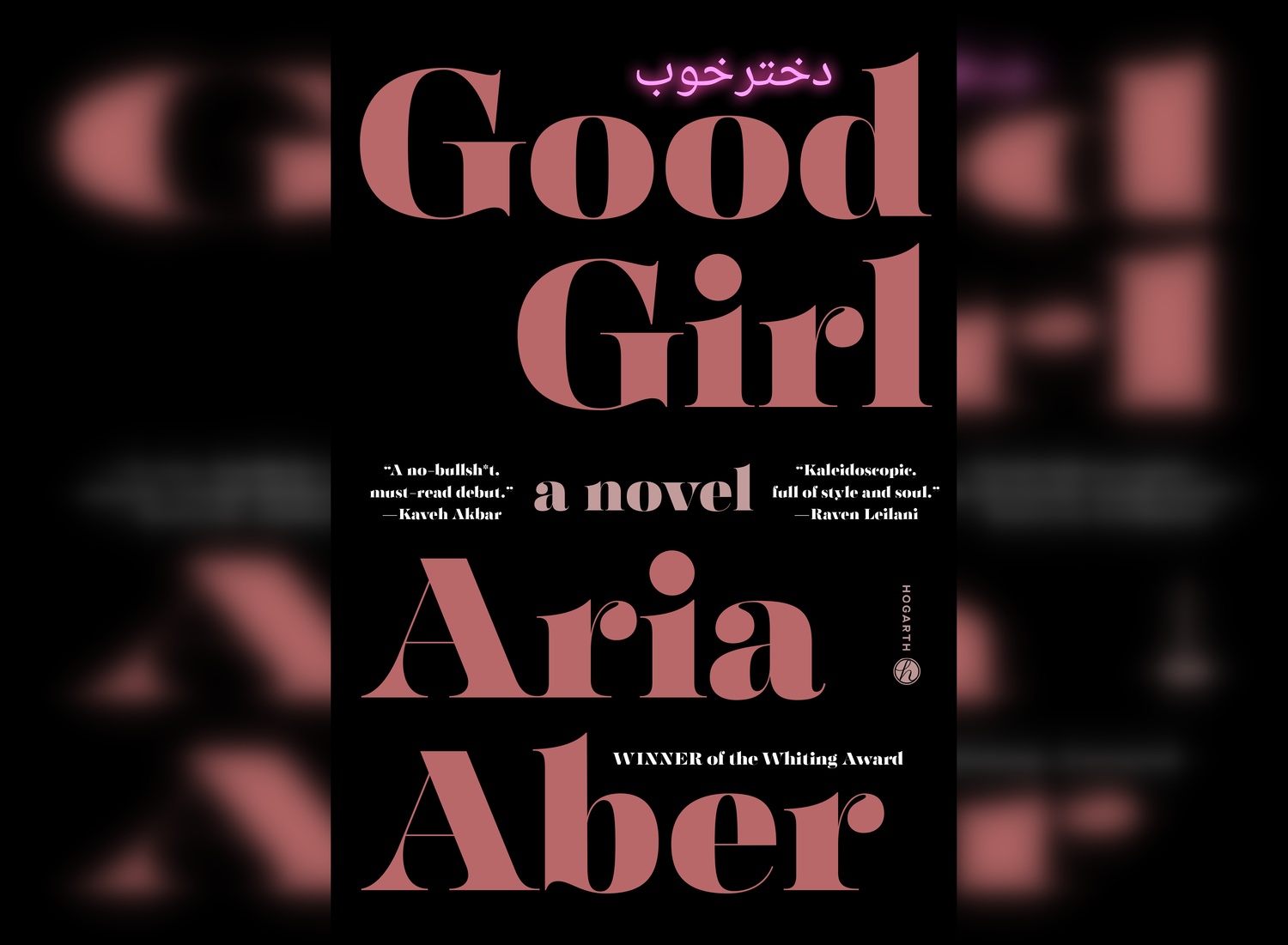

‘Good Girl’ Review: Emotional Excess and Existentialism

4.5 Stars

Aria Aber’s lyrical debut novel “Good Girl” is an addictive immersion into the gaudy and overstimulating world of Berlin nightlife, weaving together a teenager’s hazy memories with keen observations on art and human nature. Shortlisted for the 2025 Women’s Prize for Fiction, “Good Girl” masterfully chronicles the rise and fall of a young woman’s life through Aber’s poetic prose.

The story follows nineteen-year-old Nila Haddadi as she searches for “a purity of experience rather than of honor and abstinence.” The daughter of Afghan immigrants living in Berlin after 9/11, Nila wrestles with the rigid expectations of her family and rising racial tensions in Germany. Aber’s debut tells the story of Nila’s terrible mistakes as she tries to find her voice as an artist and individual amidst the endless churn of city life during the year in between boarding school and university.

Art is everywhere in “Good Girl.” Nila constantly reflects on the architecture of the city, referencing the “ghosts of the East” present in the “tree-starved DDR-style council blocks.” Many of the sequences in the novel are viewed through the cross hairs of a camera, or the windows of a train speeding through the city. Quotes from Goethe are painted on Nila’s bedroom wall, and the emotional excess of the “Sturm und Drang” movement, characterized by intense subjectivity and the rejection of Enlightenment rationalism, parallel Nila’s own experiences.

Nila lives “a double life in the city’s underbelly” to escape from the existential realization that she is “pinned to a cold, dark universe.” The Bunker, a stand-in for German nightclubs like Berghain, serves Nila as a shelter, an escape, and a prison. The place “where the machines of our bodies could roam free and dream,” the Bunker comes to symbolize Nila’s frenetic energy and constant desire for stimulation.

Aber depicts the tension between Nila’s longing for authenticity in her art and the psychological impact of unenforced boundaries with skill and sensitivity. Nila’s relationship with Marlowe — 16 years her senior — develops her skills as a photographer and model, but wreaks havoc on her mental health. In a photograph taken by her older lover, Nila looks like a bereft child “unaware of what is happening to her.” Aber forces the reader to question the cost of good art — why must artists and models suffer to produce beauty?

What elevates “Good Girl” from an angst-ridden romance to a literary masterpiece is the development of Nila’s relationship with her absent father and deceased mother. Brief flashbacks to Nila’s childhood allow the reader to glimpse moments of love and neglect, tenderness and abuse, from her parents. However, Nila’s mistrust of her parents blooms into empathy in the years following her mother’s death and her estrangement from her father.

Aber writes, “My parents were, I was only beginning to realize, intellectuals in a language I couldn’t read.”

“Good Girl” is a symphony of self destruction. Simultaneously overwrought and melancholy, incisive and honest, Aria Aber possesses a poet’s control over each word. In some ways, “Good Girl” feels more like a collection of photographs than a novel — each scene is a hyper-detailed but brief glimpse into Nila’s psyche, full of empathy for the impetuosity of youth.

—Staff writer Laura B. Martens can be reached at laura.martens@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.