News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

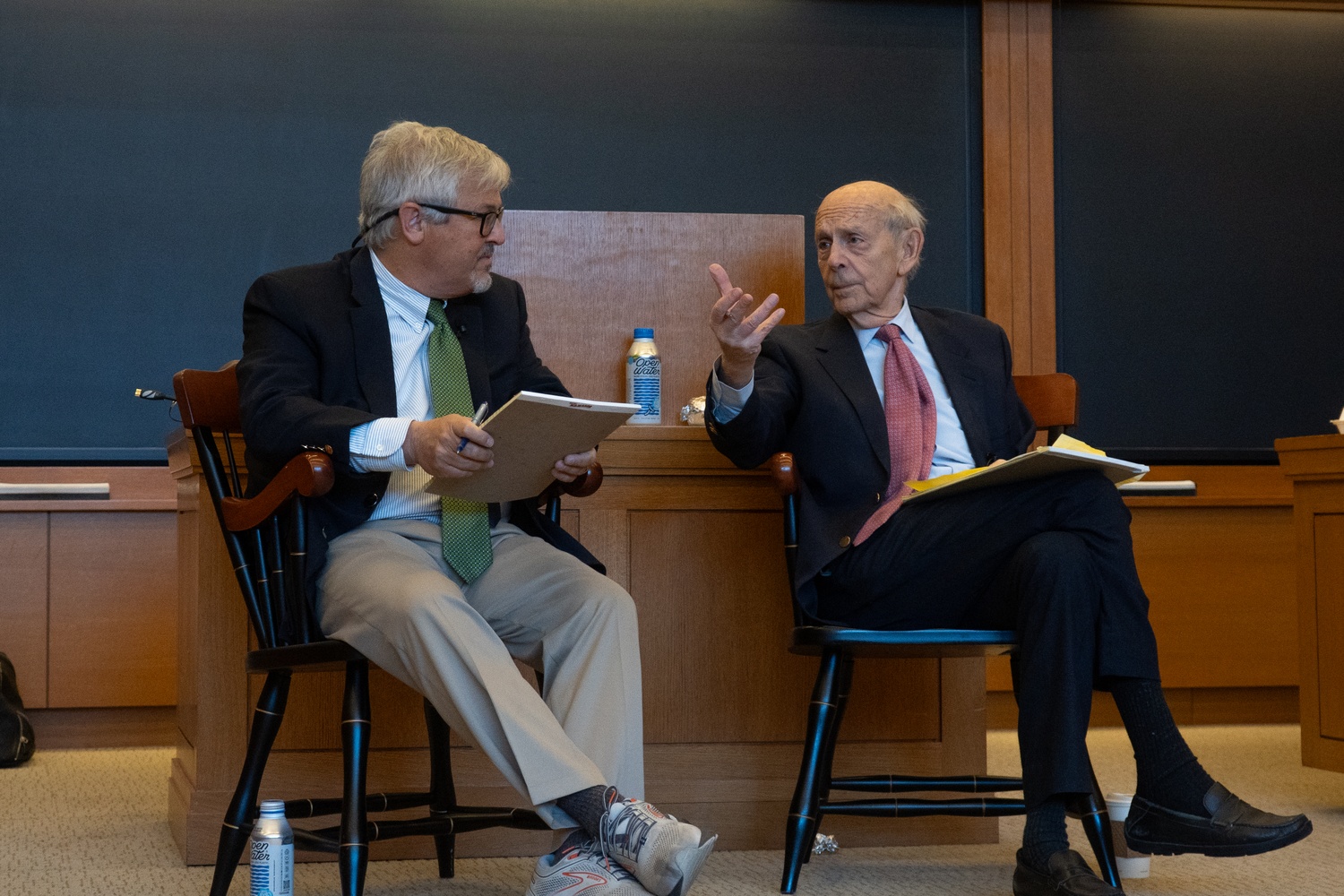

Breyer Suggests Criminal Contempt Charges For Trump Officials at HLS Event

Former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen G. Breyer said the Trump administration could be held in criminal contempt over Kilmar Abrego’s deportation at a Harvard Law School speaker event on Friday, expressing optimism that Courts would hold the White House accountable.

Breyer, a professor of administrative law and process at HLS, joined Jack L. Goldsmith, also a professor at the Law School, to discuss the evolving role of executive power in the federal government. The event was sponsored by the Law and Democracy Forum, a student-run organization that hosts panels on current events and their legal implications.

Goldsmith and Breyer discussed the legal options available to force the return of Kilmar Abrego, a citizen of El Salvador who had lived in Maryland for thirteen years before the Trump administration mistakenly deported him in March — despite a 2019 court order forbidding his removal.

The Supreme Court ruled unanimously on April 10 that the Trump administration must take steps to return Abrego to the U.S. Openly ignoring the order, the White House has defended the deportation and not attempted to facilitate Abrego’s return.

At the Friday talk, Breyer said that it was “quite possible” that high-ranking officials in the Trump administration, including Marco Rubio, Kristi Noem, and Attorney General Pam Bondi, could be held in criminal contempt for the refusal to comply.

If top officials were charged with criminal contempt by a judge, they could face a criminal prosecution and possible jail time. In such a case, a judge could appoint private counsel to prosecute the case.

Breyer cited Andrew Jackson’s refusal to protect Cherokee territories after an 1832 Court decision and the Arkansas governor’s defiance of an order to racially integrate schools in 1957 as moments in American history when the executive disobeyed the judiciary.

“But the rule of law went back,” Breyer said.

Goldsmith disagreed with Breyer’s assertion that criminal contempt would be an effective way to restore the rule of law because the only official with the power to enforce contempt is the Attorney General.

“I’m hopeful about the medium and long term, but I want to make it harder for you short term,” Goldsmith said to Breyer. “Because on criminal contempt, I don’t think that’s going to be effective at all.”

Goldsmith, a conservative legal scholar, said that the Trump administration “has taken unprecedented steps this presidency to remove legal constraints on the presidency.”

But Breyer said that despite executive overreach, he felt confident that the rule of law would stand.

“It is up to you whether we have a rule of law in the United States or whether we don’t,” he said, addressing the room.

“And if you think the government won’t pay attention to you, you’re wrong,” Breyer added.

But Breyer also expressed concern over the Trump administration’s executive proposals.

“I’m actually much more depressed now,” he said.

—Staff writer Caroline G. Hennigan can be reached at caroline.hennigan@thecrimson.com. Follow her on X @cghennigan.

—Staff writer Bradford D. Kimball can be reached at bradford.kimball@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.