Can Fenway Health Meet the Moment?

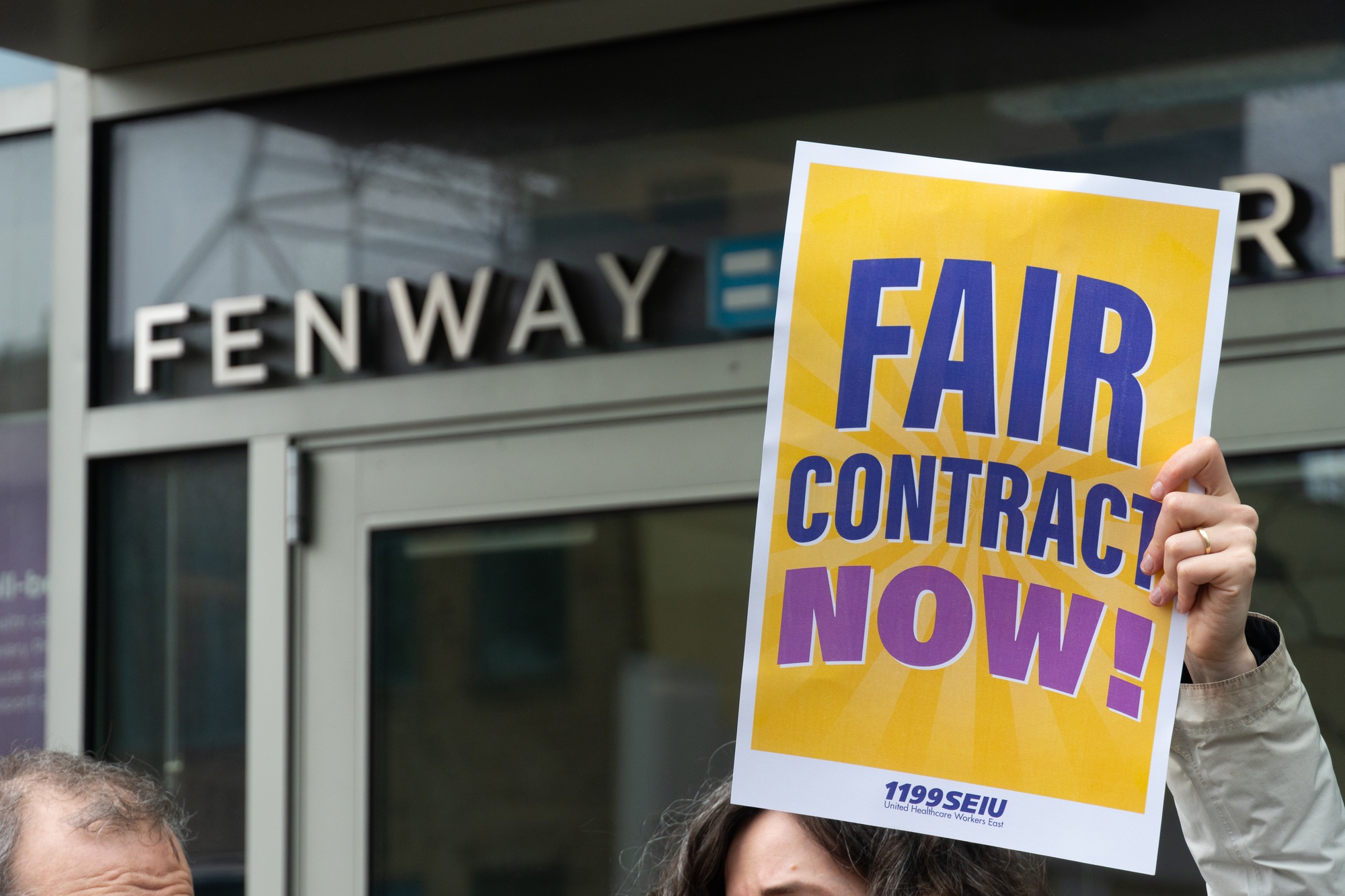

By Sophie Gao and Angelina J. ParkerIt’s a rainy morning on downtown Boylston Street, and temperatures have just dipped below 50 degrees. But the energy outside Fenway Community Health Center is palpable. A boombox blasts Dolly Parton and Beyoncé classics to a crowd of 40 dressed in matching shades of purple and yellow — the official colors of 1199SEIU, the fastest-growing healthcare union in Massachusetts. Cars honk their support as they drive past.

Then, the boombox shuts down and there’s a moment of quiet before the speeches start.

“Much of our workforce is living on wages that are below the cost of living,” Xenia S. Garcia, a bilingual outreach coordinator at Fenway Health, reads from behind a megaphone. The crowd’s boos are immediate, but Garcia isn’t finished.

“Why is this the case when our health center is located in the city of Boston, which is internationally recognized as a center for healthcare innovation?” Garcia asks.

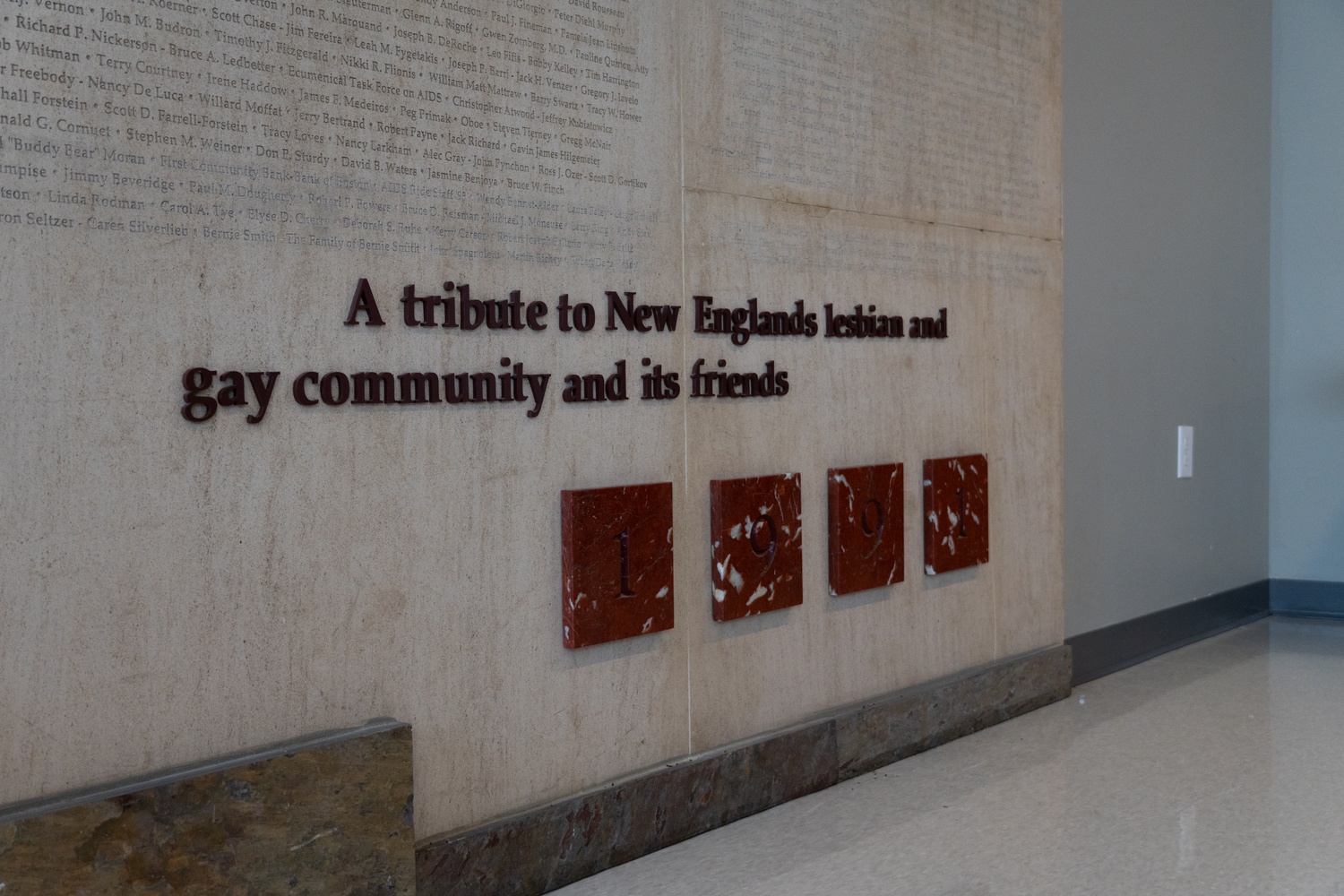

Fenway Health is indeed one of the most renowned LGBTQ healthcare nonprofits in the country: they serve tens of thousands of patients each year, lead research on issues like same-sex marriage and HIV transmission, operate on an annual budget of more than $100 million, and foster a thriving social community of gay and transgender nurses, patients, and friends.

The organization began as a free clinic run by a couple of Northeastern graduate students advancing a radical vision of community-based care. But for nearly a decade after its founding, Fenway Health’s success was not assured — they operated on a shoestring budget of only several hundred dollars per month, coming close to bankruptcy in 1980.

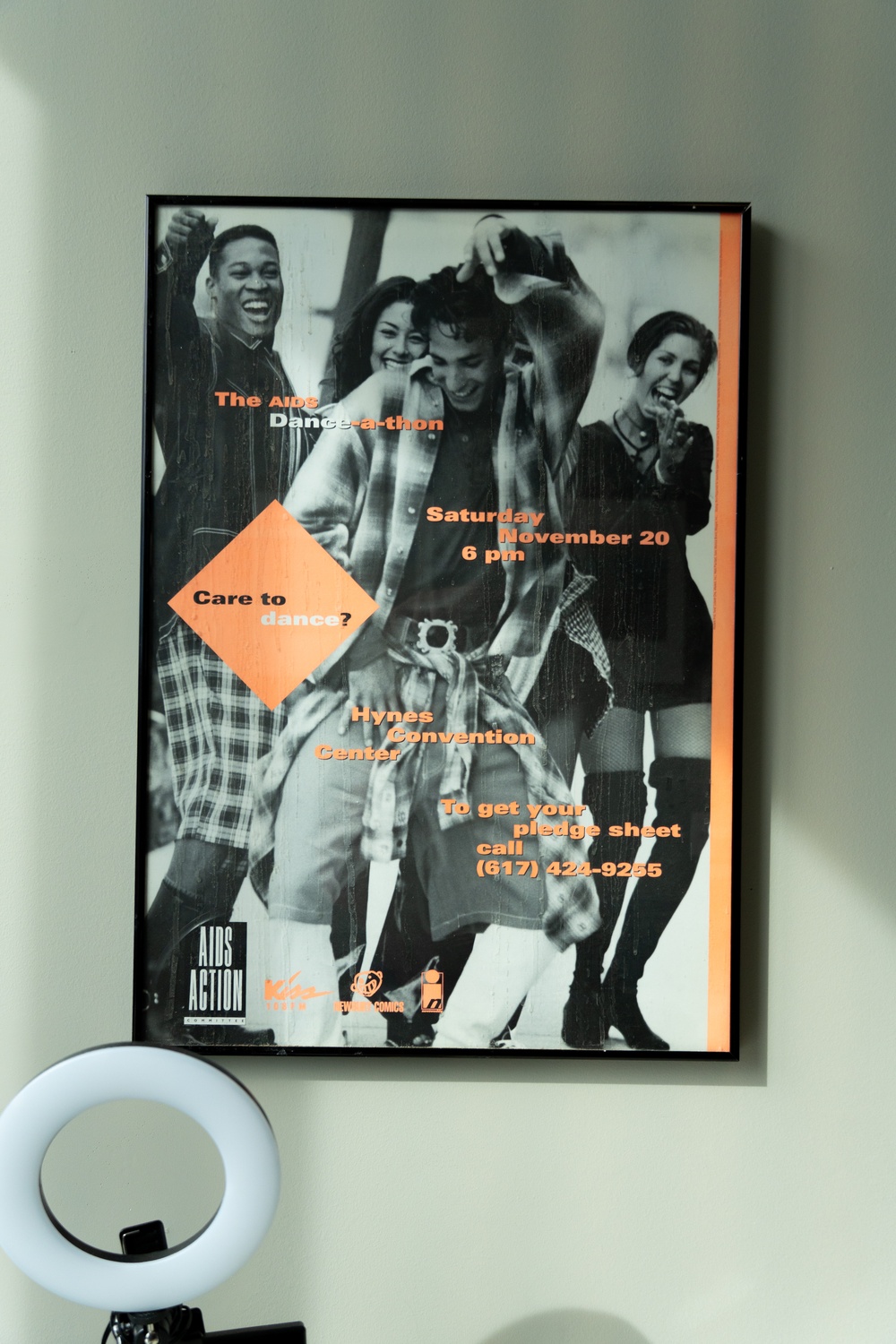

Yet as the AIDS epidemic swept through Boston throughout the ’80s and ’90s, Fenway Health grew exponentially. The center became “ground zero” for HIV research and care, according to former Fenway data analyst Ken A. Levine, attracting patients not only from Massachusetts but from nearby states, too.

Today, Fenway Health sits in a glass-and-steel skyscraper overlooking Fenway Park and an upscale oyster bar. Its name recognition reaches far and wide — and though half of its 33,000 annual patients do not identify as LGBTQ, advancing LGBTQ healthcare remains its primary goal.

But it is also an institution wracked by union troubles, harassment scandals, and financial insolvency.

In 2022, Fenway Health’s former CEO Ellen LaPointe received a 70% raise — increasing her annual salary from about $322,000 to $551,000 — despite the organization operating at an overall $12 million loss. Meanwhile, wages for rank-and-file staff members have stalled since February 2022, over 100 employees were laid off last year, and Fenway has either outsourced or downsized several of its off-site programs.

One year later, over 400 employees at Fenway formally unionized in protest of stagnating wages and reduced insurance coverage.

Finances are hardly the extent of Fenway Health’s troubles. In 2017, then-CEO Stephen Boswell stepped down after failing to fire a doctor with allegations of sexual harassment. In late 2024, the National Labor Relations Board began investigating Fenway for six alleged violations of the National Labor Relations Act, including coercion, a refusal to bargain, and retaliation against unionizing employees.

And now, more than 50 years after Fenway’s founding, access to LGBTQ healthcare is once again under threat. Trump administration cuts to funding for sexual and gender-affirming healthcare led to nearly a $3 million loss for Fenway, a number that is only expected to rise, according to Fenway Health communications director Chris Viveiros. Within the past four years, Republican legislators have passed policies banning or restricting gender-affirming care in 25 states.

Viveiros wrote in an email to The Crimson that the organization’s team is “leaning into our values” in the face of external political and financial pressures. “We are prioritizing patients, clients, and staff as we negotiate with our union partners on a collective bargaining agreement that centers our team and long-term financial sustainability,” he wrote.

The stakes of Fenway Health’s mission are high. Patients are starting to flood in from over thirty states, seeking sexual and gender-affirming healthcare that is increasingly hard to come by.

When asked about other possibilities for receiving similar care in the Boston area, long-time Fenway Health patient Cory P. O’Hayer responds at once.

“There’s no alternative to Fenway Health,” he says.

‘The Most Hippie Health Center in the City’

Just after one in the morning on a Saturday night in 2005, Boston’s notoriously diurnal nightlife is beginning to wind down. Not everyone is headed home, though. Across the street from the Boston YWCA, a crowd surrounds a van decorated with cartoon monster posters and Christmas lights. They’ve been enticed there by singing drag queen Michael Fontana, who convinced a DJ at a nearby club to lend him a mic.

A team of Fenway staff members has been working all night to chat up club and bar-goers and convince them to come to Fenway’s van to get tested for STDs or pick up free condoms — competing with a broadcasted Red Sox game for attention along the way.

By the end of the night, the team has helped 137 people.

Steven Belec, a community education coordinator for Fenway at the time, described the night as “crazy, huge and wonderful” in a written report.

“The tireless work of all the volunteers (especially Janet who had flown in from a conference only hours before) reminded me of what exactly great outreach can be. We had a group of amazing dedicated people working together to make a difference in other people's lives in a fun and highly cooperative way. I wish every night was Van Night!” he wrote.

The report concluded, “Multi-Venue outreach + fabulous drag queen + van full of nurses = successful night of outreach.”

Fenway’s van was typical of their founding vision for medical care: a grassroots, community-based operation fueled by volunteers. It was “the most hippie health center in the city,” according to Thomas Martorelli, who chaired the Fenway Board of Directors in the late 1970s.

The center began as an act of resistance to the Boston Redevelopment Authority’s plan to upscale the Fenway neighborhood, where a third of the population lived below the poverty line. From 1965 to 1967, BRA demolished over three hundred low-income housing units in the area.

Inspired in part by the Black Panther Party — whose own free clinic in nearby Roxbury doubled as a hub for political organization — David Scondras ’67, Linda Beane, and a group of graduate and nursing students at Northeastern University opened a free once-a-week drop-in clinic.

The center initially operated out of a building owned by the First Church of Christ, Scientist, before moving to the basement of an out-of-business antique shop on Haviland Street. The operation was “alternative,” says James Fishman, Fenway Health’s first psychotherapist.

A retired physician in the Back Bay donated secondhand medical equipment. Volunteers scavenged seating from a defunct movie theater. Fishman himself offered patients therapy from a former accessible bathroom.

But this volunteer-staffed model, dependent on donated medical equipment and pilfered furniture, soon proved unsustainable.

In 1979, just as Fenway Health prepared to apply for a medical clinic license from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, its executive director, Kevin T. Cunningham, abruptly left the organization. The board hastily selected Sally Deane, a former healthcare administrator at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, to take over.

According to Deane, Fenway Health “didn’t even have a computer” when she arrived in January 1980. They were missing the management and filing systems necessary to get licensed. Worse, Cunningham had been faking financial records to its board of directors. The Internal Revenue Service was on the verge of shutting the clinic down.

“I learned we absolutely didn’t even have the money to meet the payroll,” Deane says.

“For two years prior to my being hired, my predecessor had hid the fact that the health center was losing money and not making enough to support the cost of its care,” Deane says. “He presented financials to the board of directors that were false.”

“To my knowledge, there wasn’t a certified audit by a qualified auditor,” she adds.

To establish legitimacy to hospitals and grant funders, the board of directors began trying to identify a niche for Fenway Health. At the time, the center functioned as an informal confederacy of three internal groups: the gay, women’s, and elderly health collectives. But as the ’80s progressed, Fenway Health began to focus more heavily on its LGBTQ health programs, including an artificial insemination program for lesbian women — among the first of its kind in the U.S.

In August 1981, just months after Fenway had been formally licensed, Lenny Alberts, a Fenway physician, saw a young man complaining of swollen lymph nodes, fatigue, and thrush. He made New England’s first diagnosis of AIDS, then known less accurately as “gay-related immune deficiency.”

At the time, there were no specific medications available for AIDS patients, and their life expectancies could be measured in months.

“There are clinics around the country that in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the providers would be having a list of all the patients who were in the hospital and all the patients who were dying that week,” recalls Kenneth H. Mayer, who offered STD screenings at the clinic in the ’80s and now co-directs the Fenway Institute. “I mean, it was that grave.”

“You might see this person one or two times. It’s like, oh, where’s Joe? I haven’t seen him in a while. Oh, you checked the blackboard and Joe passed away. That was just how many people were falling over HIV disease back in the early ’90s,” Charlie G. Smigelski, a former Fenway Health dietitian, says. Fenway doctors kept a blackboard of people who died each week or each month due to AIDS.

Given its decade-long history of serving gay patients, Fenway Health quickly became a hotspot for STD care in the Boston area. Besides AIDS, the center identified more than half of Massachusetts’ syphilis and gonorrhea cases in the early ’80s. Doctors and students from Harvard Medical School and its affiliate hospitals filed into Fenway’s basement clinic to observe clinicians on the front line.

“Some people, particularly HIV patients, were coming from another state completely for their care,” Ken Levine, the former data analyst, remembers.

By the turn of the century, Fenway Health had emerged as a giant in Boston’s healthcare landscape. The organization formally established its research arm, the Fenway Institute, in 2001, and moved to 1340 Boylston St. in 2009, just blocks from the Longwood Medical Area, one of the most well-funded and renowned clusters of medical schools and hospitals in the world.

“People want to come to Boston for care because they want the latest in research for whatever their health challenges are. If it’s breast cancer, if it’s HIV, if it’s diabetes or what have you,” Deane explains. “And I believe that — I know now that — the Fenway Institute is the largest LGBT research institute in the world in terms of the volume of research.”

Smiegelski points to the “giants in the land of infectious disease” working with Fenway Health — figures such as Rajesh Gandhi, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School whose research specialty is HIV.

“We got to go to national conferences, and it was to talk about the work we were doing between the research department. And it was terrific,” says Peg O. Nelson, a former nurse care manager at Fenway Health.

“We had a national reputation for doing a great job,” Nelson adds.

Financial Troubles and Labor Struggles

At the union rally outside Fenway Health, Xenia Garcia hoists a large poster board painted with 1199SEIU’s signature purple and yellow in the air. As she begins her speech, she passes the sign to one of her co-workers.

“No new exec$ till we get bigger check$!” the poster reads.

A few protesters down, another sign calls for Fenway Health to expand insurance coverage for its rank-and-file workers: “Healthcare workers need affordable healthcare!”

Fenway Health has operated at a loss for the past four years, beginning in 2021 when expenditures outweighed revenue by $360,000. In 2023, the organization reported a loss of more than $12 million for the prior tax year.

In 2020, a combination of healthcare crises hit Fenway Health. The stresses of the Covid-19 pandemic led to high burnout rates, feeding physician turnover. The HIV medication Truvada lost its patent and became available at significantly cheaper prices, causing a $17 million drop in annual revenue for Fenway as of 2023.

The institution responded with budget cuts and staff layoffs. But at the same time, the salaries of Fenway’s C-suite executives increased significantly, exacerbating tensions between staff and management.

“Bargaining for a first contract is always a really difficult and challenging thing to do,” says Raedjio K. A. Naro, a family nurse practitioner at Fenway Health. “In particular, this experience is made even more challenging by the fact that the organization itself has been trying to restructure and become financially solvent, which it has struggled to do over the past many years.”

“We haven’t had a raise for three years, and that’s kind of disheartening with inflation,” says Ann E. Burke, a member of Fenway Workers United’s bargaining committee who has worked at Fenway Health for over nine years. Fenway Health’s lowest-paid workers — who tend to be medical and intake assistants — make $22 to $23 an hour.

Last year, Fenway Health laid off more than 100 employees, including people “that had been there for 20 years,” Burke says.

Financial troubles have also manifested in a widespread downsizing of the center’s health programs. Fenway’s Behavioral Health Program — already significantly hit by earlier staff layoffs — no longer offers treatment to patients who do not use Fenway as their primary care provider. In 2024, Fenway also closed Youth on Fire, its drop-in center for homeless youth, and its three Boomerangs thrift stores, which donated proceeds to HIV research.

In a June policy order, the Cambridge City Council urged Fenway to “reconsider” their decision to close Boomerangs and “provide a detailed explanation to the community.” The nonprofit More Than Words later reopened the Central Square store, but Boomerangs’ two other locations in Jamaica Plain and the South End remain closed. Similarly, Youth on Fire is now run by the nonprofit Home for Little Wanderers.

Amid the downsized programs and layoffs, many C-suite executives at Fenway Health received raises over the past four years — including a $228,000 raise for former CEO Ellen LaPointe in 2022.

“They would repeatedly tell us that they were floating the idea of management, like C-suite folks, giving themselves a 5% pay decrease in order to be able to not only retain employees, but be able to give us raises and keep Fenway afloat,” says Ronit A. Hasson, a member of the union’s bargaining committee.

LaPointe’s 2022 raise increased her salary by 70 percent.

“You’re telling everybody that you’re considering taking a pay decrease, but you secretly gave yourself a raise,” says Hasson. “It’s so brazen.”

LaPointe did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

For some, this disconnect is a far cry from the experience of working at the institution in past years.

“When I first started at Fenway, there was a whole different attitude and presentation towards the staff. We used to have these huge holiday parties at the Copley Marriott in Boston with food and entertainment,” reminisces Burke, who has worked at Fenway Health since 2016.

Hasson also recounts a gradual distancing of Fenway Health executives from their rank-and-file workers. A few years earlier, Hasson says, when employees wanted to voice concerns, “we could literally ask the CEO, the CFO, these questions directly, face-to-face.”

Now, Hasson says, communication can be difficult. According to Hasson, Fenway Health disabled Zoom’s chat feature for messaging executives during monthly staff meetings and hired new HR representatives to act as intermediary communicators between staff members and executives.

Fenway says “‘we appreciate our staff’ and so forth,” Burke says. “But they don’t. They’re not following that up in good faith with the contract.” Though Fenway Workers United became official in the fall of 2023, the group has yet to successfully negotiate a contract with executives.

Sabel A. Flynn, a former Fenway nurse, says the recent revenue loss and ensuing budget cuts and staff turnover have worsened the patient experience.

The nursing department “sort of became the apology department,” Flynn says, “because we were interfacing with patients so much as they were experiencing this horrible admin turmoil.”

For Tony Case, who started going to Fenway for primary care services when he moved to Boston six years ago, the Covid-19 pandemic marked a downturn in Fenway Health’s quality of care. “I was very angry as a patient, because I had received such wonderful care there,” Case says, noting that this trend was not “particularly unusual” for the healthcare industry at the time.

“When you walk in, there’s this pervasive dysfunction,” says Cory O’Hayer, the longtime patient. He describes a front desk staff that is unresponsive to his needs, dwindling counseling offerings, and friends who struggle to make appointments.

Trouble accessing care is a common complaint: five patients we spoke to expressed concern over long wait times, dropped appointments, and physician turnover.

“My doctor left,” says Brianna Wu, a patient at Fenway for six years who moved with her doctor to Beth Israel Lahey Health. “It was very, very challenging to get an appointment there. The quality of it drastically dropped.”

For Case, however, Fenway has made a “concerted effort to get back on track” to pre-pandemic standards. For him, it’s enough to renew his goodwill toward the clinic — he’d considered switching providers immediately following the pandemic, but now feels reassured that Fenway will continue to provide quality care.

“I believe in it so much as an institution,” he says.

An Alternative Vision of Care

When Ann Burke — the case manager on the bargaining committee — picks up the phone on a Wednesday afternoon, she’s in the middle of planning a bowling outing for the coming weekend with transgender support group she runs for Fenway Health on Cape Cod.

“We do a lot of social things also. And so I love what I do,” Burke says.

Part of Fenway Health’s draw — to patients and employees alike — is the promise that it is a social community as well as just a healthcare institution. But the dividing line between community and care is not always clear: several staff members said they wished to discuss personal shared experiences with their patients, a move their managers said overstepped the bounds of professionalism.

“I think many of us come to work at Fenway because it’s an LGBTQ Health Center, and we bring with us our lived experience of being an LGBTQ person,” says Tommy J. George, a coordinator in the sexual health clinic who previously worked at the Fenway Institute.

“We’re working in queer healthcare,” he adds. “And I think these ideals of professionalism and to not share your personal experiences contradicts the mission statement of the health center.”

The basement clinic of the 1970s once grappled with similar tensions. The Women’s Health Collective, one of three early coalitions that made up Fenway Health, argued that women — at the time largely volunteers — should serve as healthcare providers for other women.

The board, led by Thomas Martorelli, eventually voted to remove the Women’s Health Collective altogether. If they continued providing volunteer-based care, Fenway Health would not have received state licensure, which required care to be provided by licensed practitioners.

“It was one of the most painful experiences,” Martorelli says. “But the existence of the health center was at stake.”

Today’s conflict between rank-and-file workers and administration raises the same old question. Just how alternative and community-focused should Fenway Health’s model of care be?

“Everybody was there because they wanted to be looking after our community,” says Charlie Smigelski of his experience at Fenway in the ’90s. He recalls a yearly Fenway contingent at the annual Boston Pride parade. “The people that are working there, they’re just great people, because they have that sense of — ‘hey, we want the community to be prospering. We want the community to be nurturing.’”

But Fenway’s “community,” he adds, was not limited to Boston’s LGBTQ population. Smigelski remembers a nurse practitioner, Marcy, who told him about a woman “in a hetero relationship” who came to her for advice on having anal sex with her boyfriend. Marcy, he says, told him: “I’m just glad my person felt that I was approachable on that topic.”

Today, Ronit Hasson, the Fenway nurse, alleges “a censorship of speech” during meetings with management and directors of sexual health programs. “There are some managers that are so far removed from what we do. And they directly oversee us, but they don’t come to clinic, they’ve never watched a patient interaction,” she says.

“It’s frustrating,” she adds. “Sometimes, it can feel racist, it can feel transphobic, it can feel homophobic. And, at its core, it’s just fundamental disrespect and willful ignorance and a refusal to engage with your direct subordinates.”

Sabel Flynn, the former nurse, felt similarly that the personal connections he shared with his patients ended up taking a backseat. “I’m openly trans, and I had a nurse coworker who was nonbinary, and I knew multiple trans people who would be brought on with the promise of their own personal expertise, as a peer for our patients,” says Sabel Flynn, the former nurse. He worked specifically with teams specializing in trans youth and family medicine. “I felt like I was able to offer a really unique angle to the care I was providing,” he says.

Due to budget cuts, Flynn says, he quickly became overbooked and overworked, spending less “time and energy” on the trans youth program. “It was really easy for trans employees to find solidarity with our trans patients and their families,” he says. “And that was totally disregarded because we were expected to prioritize the finances of the company more than the quality of the care provided.”

Burke says that despite her objections to messaging from higher-ups in the company, she’s found a calling in the organization’s mission. Besides the bowling outing, she’s also planning a wedding shower for a few members of her transgender support group, who are getting married later this year. “I love what I do,” she repeats. “I believe in Fenway’s mission. I just am not happy with Fenway’s management.”

‘A Moving Target’

As of this month, it is a felony to provide gender-affirming medical care to transgender youth in six states. Nineteen more have bans on both medication and surgical care, and an additional two prohibit gender-affirming surgery. On the federal level, the Trump administration has vowed to revoke funding from any programs that facilitate gender transitions for minors.

As Fenway Health scrambles to resolve its joint labor and financial crises, it is confronted with a new threat to its mission to serve the LGBTQ population: a mounting Republican campaign against gender-affirming care and healthcare providers as a whole.

“At Fenway, we have seen an uptick in those seeking gender-affirming services,” says Dallas M. Ducar, executive vice president of donor engagement and external relations at Fenway. She estimates that patients from 30 different states have come to Boston for care they cannot access at home — a jump that she says “puts the strain on capacity” for care at Fenway.

Fenway’s research branch, the Fenway Institute, also faces a decimated financial portfolio as the Trump administration carries out mass cuts to the National Institutes of Health. At least 12 of the institute’s 27 NIH grants have been terminated since Trump took office, totaling $1.8 million worth of funding. According to Kenneth Mayer, the institute’s medical research director, the cuts amount to “probably at least a third” of Fenway’s active research portfolio — and the $1.8 million figure is almost certainly an undercount, given that the Fenway Institute will feel the losses from cancelled grants at its partner institutions. The total loss, he says, is “tens of millions of dollars.”

The impacted programs are wide-ranging: the development of a smoking cessation intervention designed for transgender people, studies focusing on gynecological health disparities in queer women, and a survey of electronic medical records to track the diffusion of HIV prevention medications. A recent Trump administration order also slashed funding to the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network, which funds HIV prevention research at sites across the nation, including the Fenway Institute.

“It’s a moving target,” says Jennifer E. Potter, who co-directs the institute alongside Mayer. Fenway Health receives $20 million a year in federal funding. Though around $3 million in grants has been revoked so far, more could be on its way.

“We’re very uneasy,” Mayer says. “We don’t know if they’re all going to be cut or what, because there hasn’t been a rhyme or reason for this other than bias on the part of the people who can make these decisions.”

Since February, the Trump administration has been terminating grants for research it views as ideologically driven — largely centering on projects focusing on the LGBTQ community. Keywords like “sex,” “LGBTQ,” “transgender,” and “biased” appeared to be correlated with terminated grants.

These cuts have impacted projects across Boston’s hospitals — The Crimson reported on April 11 that more than $110 million in grants funding projects featuring similar keywords were canceled at institutions like Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital since late February.

“LGBTQIA+ health research not only benefits LGBTQIA+ people, but it benefits the healthcare system as a whole,” Potter says. For example, she explains, anatomical inventories — treating patients based on their organs rather than their presenting gender — benefit transgender individuals, but also help cisgender women who may not realize they still need cervical cancer screenings after hysterectomies.

Since the 1980s, Fenway Health has led the way in infectious disease and health policy research for LGBTQ individuals. In the lab, Fenway-affiliated researchers have studied the mechanisms of HIV transmission, conducted clinical trials for HIV/AIDS treatment, and explored how mental health problems impact gender minorities like transgender individuals. It was also the first health center to test for HIV antibodies in New England.

Potter, who in her role mentors early-career scientists and directs a joint medical fellowship between Harvard Medical School and Fenway Health, says the sudden research pause will have far-reaching impacts. “If we don’t have as many scientists working on these things,” she says, “that disrupts our ability to train the next generation of researchers who are going to be focusing on these issues and carrying the field forward.”

Mayer, looking back on decades of Fenway research, says it “took a number of years” for the federal government to recognize the importance of healthcare for sexual and gender minorities.

Mayer likens the threat of Trump’s funding cuts to “Sisyphus rolling the boulder up the hill, and it feels like the boulder rolling back down.” He adds that Trump’s funding cuts will force Fenway to rely more heavily on its non-federal sources of funding, like charitable foundations and donors from the private sector.

As for how they will roll that boulder back up?

“It’s not really about coming back, exactly,” Potter says. “It’s about — how do we continue strong, to serve our patient population and our communities? And then how do we rebuild, maybe in new ways, the research and the education and the innovation as we move forward?”

***

In some ways, Fenway Health is right back where it started: an outsider to the prevailing political current, relying on donors to maintain its mission, struggling to stay afloat amid financial troubles.

Yet today’s glass-and-steel complex on Boylston Street is a far cry from the church-owned building where the clinic was born. As a giant in the world of LGBTQ healthcare and research, Fenway’s survival is now vital for the tens of thousands of patients who depend on its services.

Calling from California, where he moved after leaving Fenway in 1985, James Fishman recalls the clinic’s early fight for survival as the center faces the looming challenge of a hostile administration.

“We were very resilient as gay and lesbian people back then. We are resilient people and strong people, and we will stand up,” he says. “We’ve made it through rough times before, and we’ll make it through rough times again. That’s less about Fenway, that’s less about the building. It’s just what I want you to hear.”

Ronit Hasson, the nurse who noted Fenway executives’ distancing from staff, didn’t know much about Fenway’s history when she started working there in 2021 — nearly 40 years after Fishman left. But now, even as she criticizes Fenway’s management, she praises its mission: “What an incredible history this place has — not only as a haven for the queer community, but as a safe place, a place to be yourself and connect with others.”

“It is truly a port in the storm, and we need it more than ever,” she says. “We needed it thirty-some-odd years ago, and now we need it truly.”

—Magazine writer Sophie Gao can be reached at sophie.gao@thecrimson.com. Follow her on X @sophiegao22.

—Staff writer Angelina J. Parker can be reached at angelina.parker@thecrimson.com. Follow her on X @angelinajparker.