The Urban Agriculturalist at North Allston Farms

To any green-thumbed reader of Fifteen Minutes eager to start their own farm, please know that you do not need a chicken. Include pigs, cows, horses and ploughs on this list as well. You can forgo animals, industrial equipment, and farmland altogether. For the urban farm, one needs not much more than a pitcher of seeds, a massive bag of dirt, and a dozen eager mouths to feed.

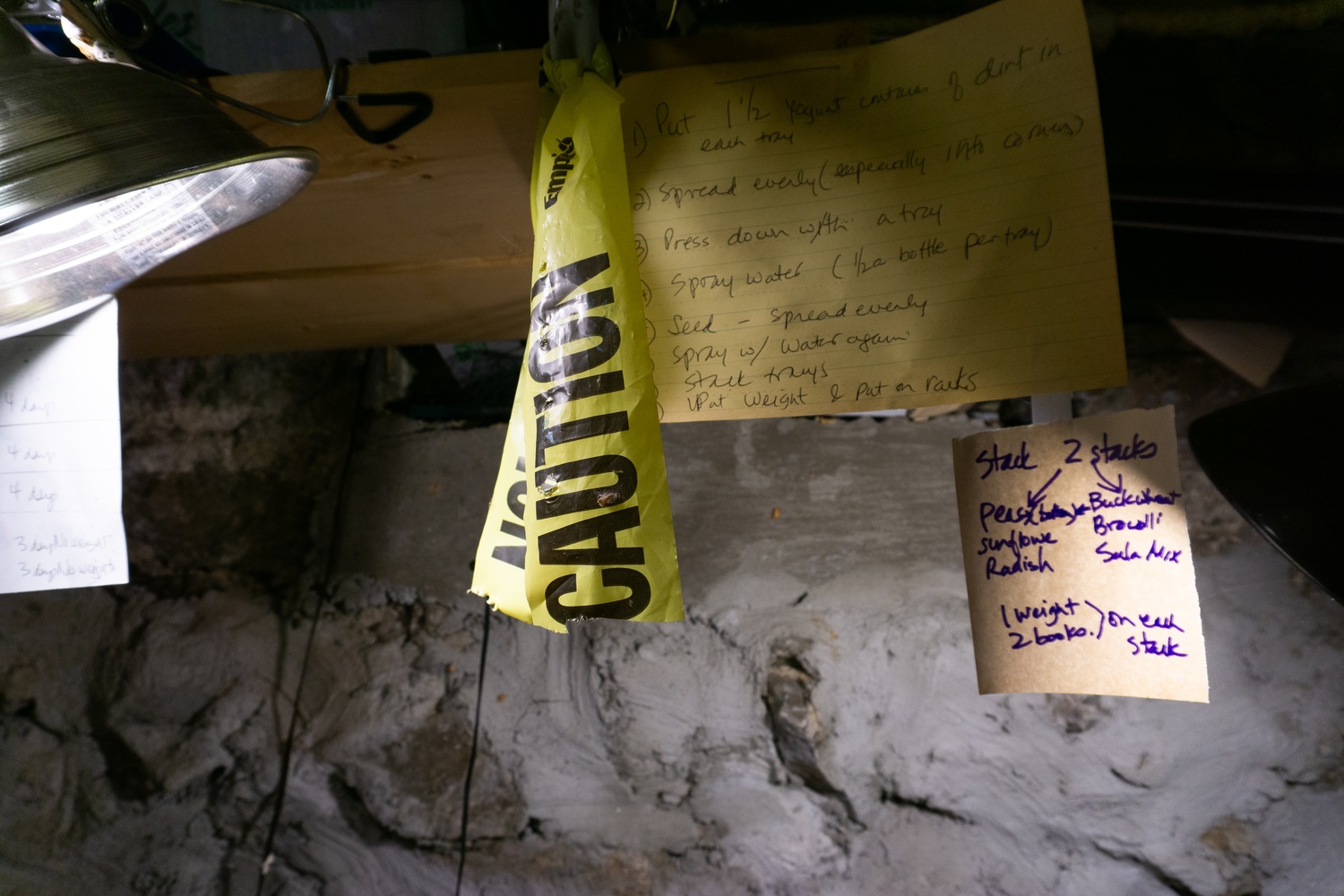

This comes as a lesson from North Allston Farms, an urban microgreens grower just minutes away from Harvard’s Allston campus. Microgreens, the seedlings of adult vegetables, are the farm’s only crop. Due to the microgreens’ small size and dense growth, founder and sole farmer Rita L. Vaidya is able to grow them indoors and even below the earth. In the basement of her home, arranged on a metal shelf fixed with purple LEDs, are trays of baby vegetables. Broccoli. Peas. Arugula. Cilantro. Sunflowers. Tomatoes.

Beyond the taste of her produce, Vaidya sees her ergonomic pasture as an illustrative guide to personal empowerment and self-sufficiency.

“I think people think you can’t grow,” Vaidya says. “I can grow. You can grow. Anyone can grow.”

Though Vaidya founded the farm just two years ago, she has never been a stranger to the garden. Born in northern India, Vaidya says her relationship with gardening began quite young, as her father worked in forestry management. As a child, she traveled with him on forestry tours in the mountainous countryside.

“The love for the environment kind of came from there. We had a garden growing up, and I think that was in my genetic makeup, or something environmental,” she recalls.

Once she moved to Allston — where she’s now lived for almost 30 years — Vaidya continued the practice, growing vegetables in her backyard for cooking. This domestic garden, separate from her microgreen farm, is another project in self-reliance: to grow all her own vegetables, including tomatoes and other crops that are not conducive to growth in the area’s climate.

“I try to grow okra, because I grew up eating okra — not a very summer crop for the Northeast — but I still try to grow it, because that’s what I like to eat, some little things from home,” Vaidya says.

Before her farm, Vaidya was also a data-scientist consultant, working part-time while tending to her outdoor beds. Between work and the family garden, she nurtured a complicated dream to start a farm in the countryside — no easy feat while raising two children in Boston, a city she had grown to love.

“I was like, ‘Oh, I love gardening!’ and I thought, ‘I want to be a farmer,’ you know, maybe buy land elsewhere, but I love being in the city,” Vaidya says. “Second, it’s a lot of physical labor. And I am 57.”

Though she was resigned to these complications, a series of coincidences led to the creation of North Allston Farms. First: an online shopping error.

“I started my own seedlings from my outdoor garden. By mistake, I ordered the wrong seedling trays to start,” she says.

Curious about her new “microgreen trays” and later stuck at home with a sprained foot, Vaidya perused social media to learn more about microgreens. Then she encountered her second coincidence: a page on Instagram advertising a class on microgreens, as well as a community of microgreen farmers looking to turn their crop into profit.

Beyond their space efficiency, microgreens are heralded as nutrient-dense and flavorful additions to any meal. The nutty sunflower seedling and spicy baby radish stems made the plants a habitual addition to her daily eating habits. “It’s not just a garnish,” Vaidya says.

Her care and enthusiasm for the microcrop garnered the farm 10 to 15 regular customers, who collect their produce every two weeks on Fridays, in sync with the 12-day growth and harvest cycle. Keeping commerce on her front porch, she finds selling to individual customers preferable to fulfilling bulk orders for restaurants and businesses.

“I like the idea of selling to individuals, because I like to know who’s buying from me. I like that one-on-one interaction,” Vaidya says.

North Allston Farms has steadily grown, whether from conversations between Vaidya and farmer’s market attendees or by word-of-mouth among her neighbors.

Vaidya sees the farm not simply as a business, but as a garden and space of education for anyone hungry and curious. When not tending to her crop, she hosts workshops throughout Allston, advertising “the joy of tasting and growing microgreens while learning where your food comes from.”

At these workshops, Vaidya explains the process of growing and tending to home-grown produce. She held one at the Harvard Ed Portal last fall, attended by local grade school students and their mentors. Her other workshops have taken place within the Allston Brighton Health Collaborative, where she also serves on a subcommittee for planning green spaces in Allston.

“If I lose a customer because they’re starting to grow their own microgreens, I have succeeded,” she says.