The Unraveling of the New England Primate Research Center

For 50 years, the New England Primate Research Center pioneered research in HIV, Parkinson’s, and addiction. But as a series of animal misconduct allegations eroded the center’s legacy, Harvard, the Medical School, and the NEPRC itself struggled to control a slow collapse.

The Unraveling of the New England Primate Research Center

For 50 years, the New England Primate Research Center pioneered research in HIV, Parkinson’s, and addiction. But as a series of animal misconduct allegations eroded the center’s legacy, Harvard, the Medical School, and the NEPRC itself struggled to control a slow collapse.On May 24, 2014, an Oregon Zoo veterinarian gently shook the cooler box that had become a temporary home for a family of nine quarantined cotton-top tamarins.

Native to northwestern Colombia, the cotton-top tamarin is critically endangered, with fewer than 6,000 living in the wild. They are a small primate, with each one usually weighing no more than one pound, and named after its tuft of snow-white hair.

On that day, the vet saw a mane flowing out of the makeshift container and gently felt the tamarin’s head. It was cold to the touch.

She tore off the lid and found four of the tamarins dead. She called another vet and cut open the other container to discover two more deceased tamarins. The two vets rushed them into an autopsy room; they disinfected the cooler boxes, and, while triaging the survivors, discovered that one of the remaining tamarins was an infant and its parents were among the dead.

The incident is detailed across more than 400 pages in an investigation by the United States Department of Agriculture, obtained by The Crimson through a public records request. The report shows photographs of the primates’ cages, pages of affidavits from witnesses, medical reports, and necropsies of the dead tamarins. All names are redacted. Investigators never determined the tamarins’ cause of death.

In Oregon, as vets searched for information on hand-rearing the infant, the staff realized that they needed to make a phone call. The tamarins were in quarantine because they had been shipped from Massachusetts 48 hours prior.

In the zoo autopsy room, one of the vets turned to another. “Can you call Harvard?” she asked. “I don’t want to call Harvard… I’m afraid I might cry.”

***

The nine cotton-top tamarins were sent to the zoo from Harvard after its closure of the New England Primate Research Center, a national repository for lab monkeys that had pioneered research in HIV, Parkinson’s, and addiction for decades. The NEPRC was one of eight centers founded by the federal government to research, care for, and breed primates as a national biomedical resource.

Though underneath Harvard Medical School, leaders at the time characterized the NEPRC — located in Southborough, Massachusetts — as an entirely separate institution, far removed from HMS’ Longwood campus and from the watchful eyes of Harvard’s central administration.

The NEPRC had faced repeated allegations of animal misconduct, beginning with a dead monkey left in a cage during a pressure washing in 2010. Over the next two years, three more monkeys died in incidents at the facility.

The University, Harvard Medical School, and the center struggled to control a slow collapse. As the center’s legacy eroded and an asset for the university increasingly became a liability, HMS discovered deep-seated mismanagement that had long endangered primates and the credibility of the center’s research. In response, HMS attempted repeated reform.

Leaders at the center thought they could preserve their research. Researchers nationwide who relied on the center’s work opposed the loss of a crucial primate facility, fearing setbacks in scientific discovery. Senior HMS leadership, who had long let the center run itself, believed their three-year intervention had fixed the problems.

But on April 23, 2013, Harvard Medical School announced that it would be shutting down the facility, citing “constrained resources.”

Then-University Provost Alan M. Garber ’76 — now Harvard’s president — praised the center’s staff in 2013 for their contributions to “life-saving research,” but stressed that the University was left with no other financial choice.

“Difficult choices must be made at a time when all of the revenue sources upon which a research university depends are under pressure, and the future of federal support for scientific inquiry seems uncertain,” Garber said at the time. (Garber did not respond to a request for comment.)

Preventable primate deaths had twice paused the center’s research, but its closure shocked primate researchers around the country and administrators at the National Institute of Health, who had funded the facility for nearly 50 years. The NIH was more than willing to fund the center for another five years, with NIH administrator John Harding telling the Boston Globe at the time that the closure was “Harvard’s decision, not ours.”

Costs were at the root of the NEPRC’s closure, but they were not purely financial.

The decision had to weigh the costs to researchers left without jobs, the costs of shipping primates around the country, and the costs to a University whose reputation was quickly being attached to a facility in the woods, 30 miles away.

The Lab in the Woods

For 50 years, the center sat alone, sheltered in a forest of tall pines.

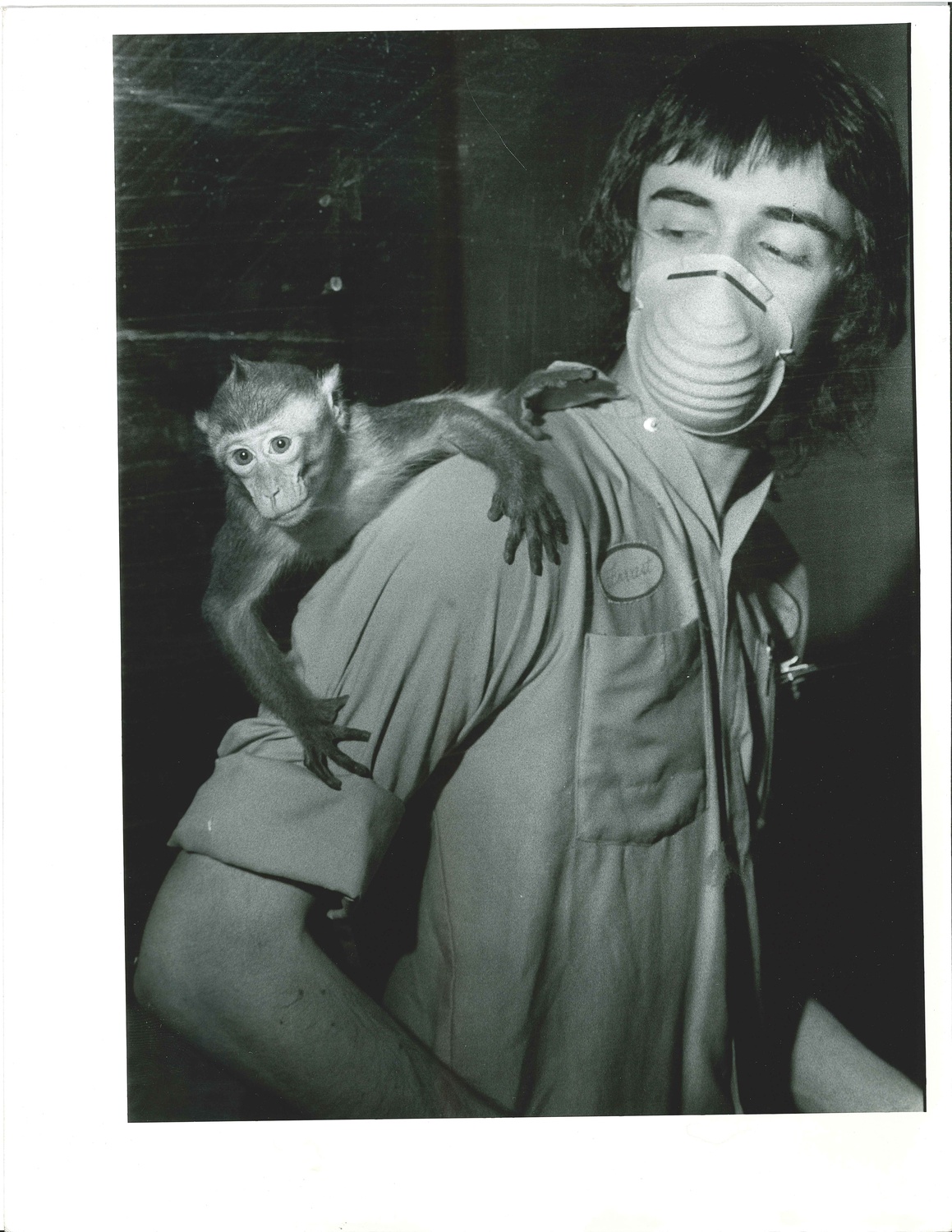

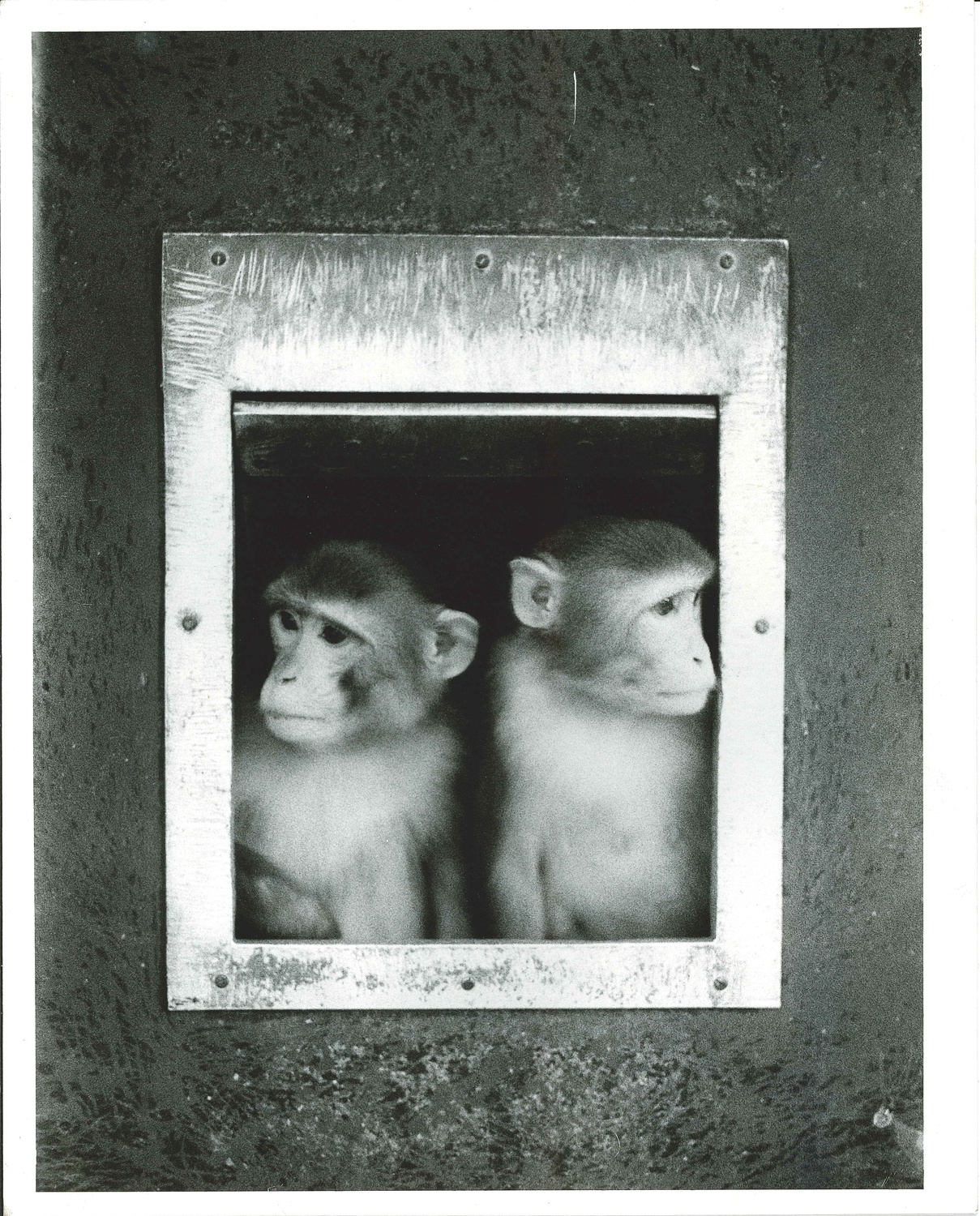

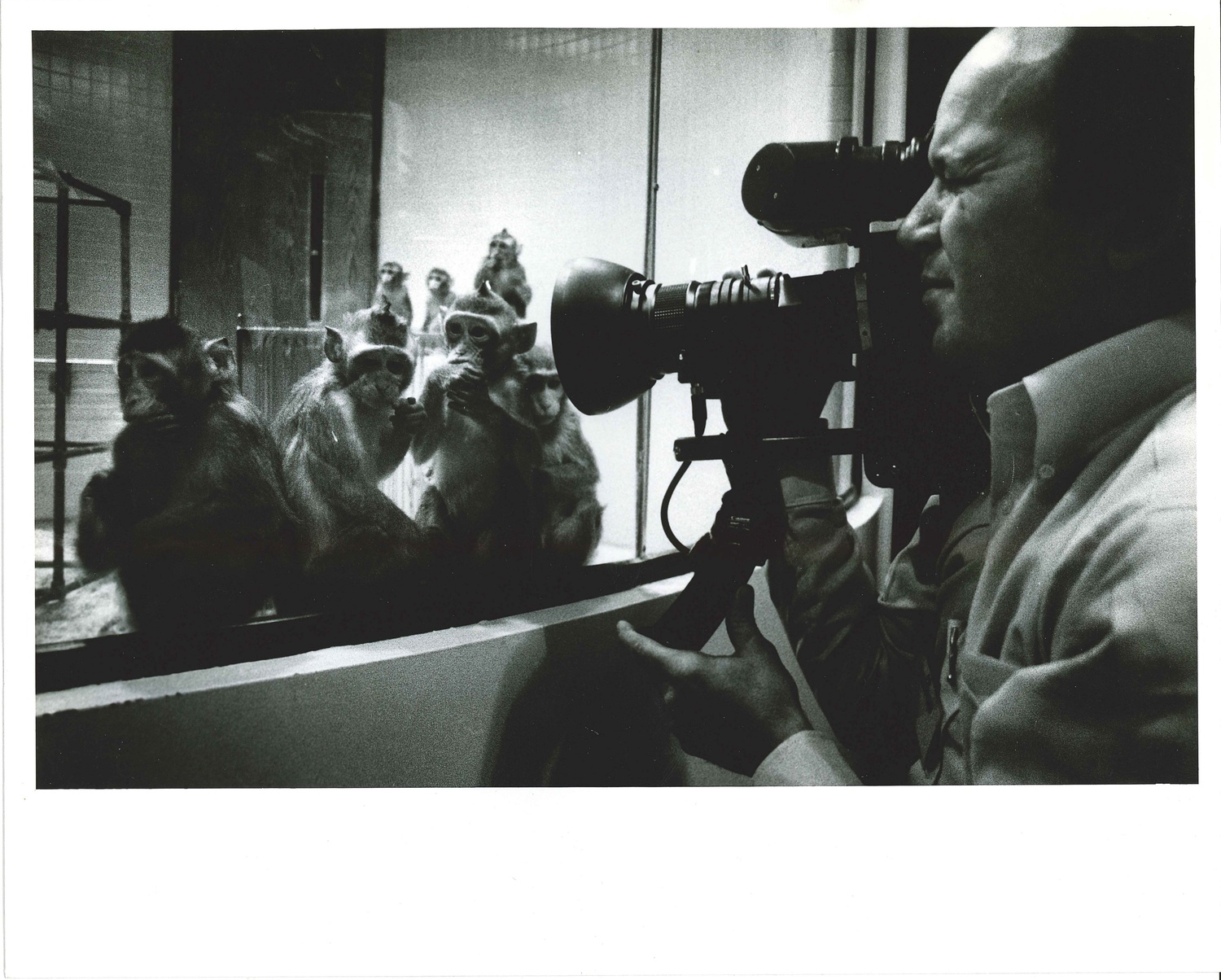

The NEPRC functioned under Harvard’s leadership but served an expansive national network of scientists. On the center’s grounds, researchers bred, raised, and cared for monkeys — known to the scientists who study them as Non-Human Primates — that would be utilized for biomedical studies.

The facilities in the Southborough woods made up one of many national primate centers spread throughout the U.S. The centers date back to 1956, when James Watt, the director of the National Heart Institute, traveled to Sukhumi in Soviet Georgia. He visited a primate facility studying hypertension, which the Soviet government had invested heavily in despite staggering financial losses in World War II.

Watt returned to the U.S. with a pitch for Congress: a collection of regional centers, aimed at preserving the national stock of primates for generations of American scientists.

Watt’s proposal came just after Jonas Salk had used rhesus monkeys to develop a polio vaccine. Driven by Cold War competition and one of the greatest medical achievements of the 20th century, Congress was happy to explore Watt’s plan and appropriated $2 million in the program’s first year.

In 1961, Congress approved and appropriated funds for a center run by Harvard. Harvard considered sites in Boston and Belmont with no success until the first director of the center, Bernard F. Trum, discovered a plot of land while driving from his hunt club in Southborough, Massachusetts.

By the 1990s, the NEPRC had gradually grown to function on its own. HMS and the University rarely exercised any direct control of the center, with officials often not aware of the center’s place in HMS’s research portfolio and deans of HMS rarely, if ever, conducting visits. Every summer, employees gathered for a big picnic on the grounds, bringing dunk tanks and other summer camp activities, according to Welkin Johnson, a former researcher at the NEPRC. Everyone would come, from the cafeteria crew to the janitorial staff to the researchers and veterinarians.

R. Paul Johnson, a physician and immunologist and the last director of the center, compares it to the Richard Scarry book, “What Do People Do All Day?” — the children’s book that follows a dizzying cast of anthropomorphic animals across a bustling day in Busytown.

“It’s really a very complex ecosystem of a lot of different roles that come together to keep a primate center going,” Johnson says.

An administrative staff managed the finances, human resources, and operations. Animal caretakers worked with the primates to feed them, clean their cages, and provide water. The researchers included principal investigators of labs, postdoctoral fellows, Ph.D. students, and graduate students. Veterinary technicians trained and handled the animals, drew blood and provided medication, and kept an eye on them to ensure they were healthy.

The veterinarians were tasked with managing two distinct types of primates: New and Old World monkeys. Old World monkeys consisted of larger species, including rhesus macaques. They were often heartier and easier to perform experiments on. New World monkeys, on the other hand, were small and fragile, and often not susceptible to rote experimentation. They included squirrel monkeys and cotton-top tamarins, which were frequently used for the study of Epstein-Barr Virus, also known as mono, and inflammatory bowel disease. A permit from the Fish and Wildlife Division limited research on the endangered cotton-tops, meaning researchers could never sacrifice a cotton-top tamarin for an experimental goal.

“We were all there together,” Welkin Johnson says. “I have good memories of it, except, you know, I had to drive to a mall to get a cup of espresso or something.”

An Urgent Mission

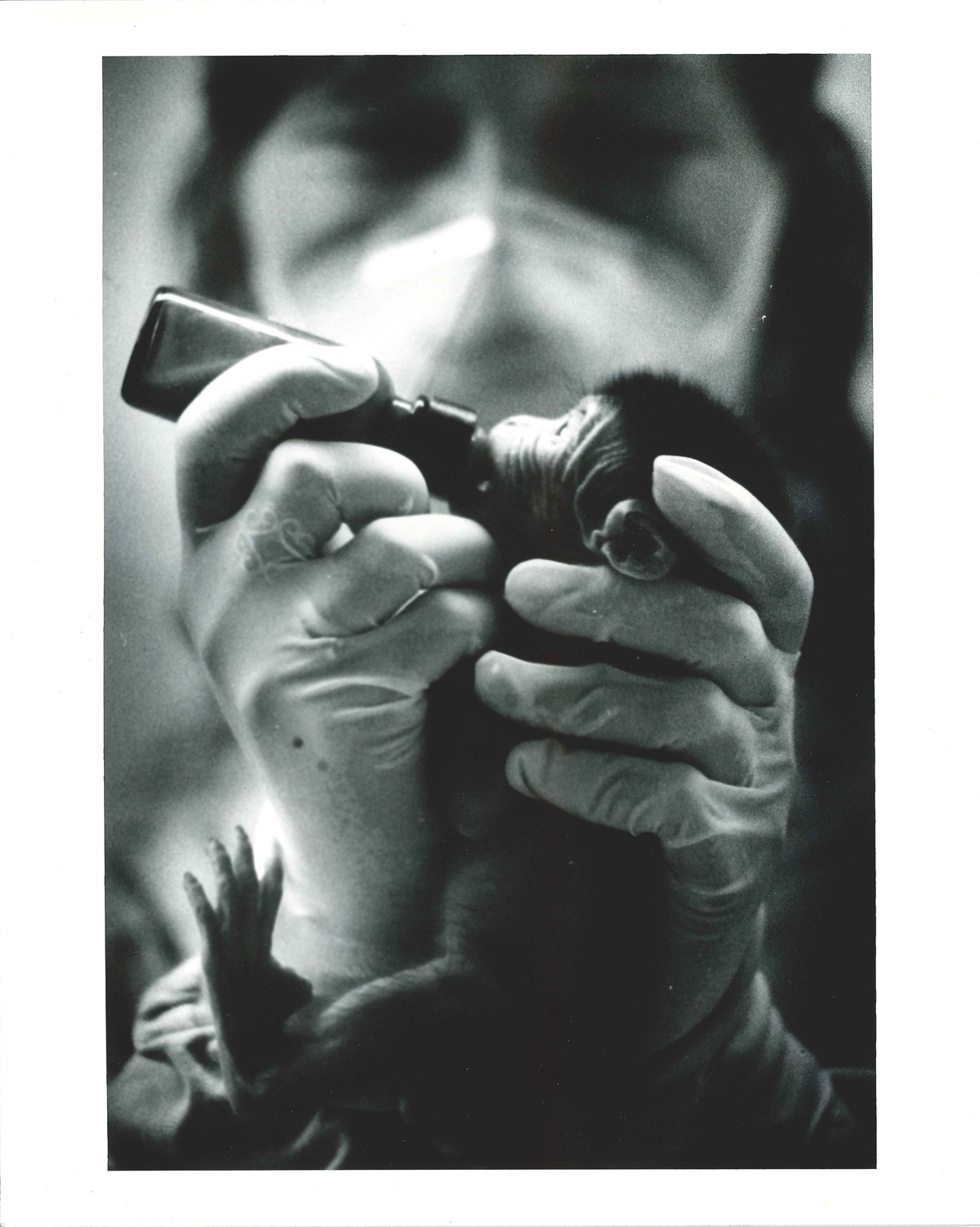

With the outbreak of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the U.S., the NEPRC established a name for itself as a premier center for research on the virus. The center’s discoveries were spearheaded by the work of Ronald C. Desrosiers, who in 1984 discovered simian immunodeficiency virus, the primate version of HIV.

With Desrosiers’s primate model, researchers and their grants came to the NEPRC to search for cures and to learn from the best in the field.

During the height of the epidemic, patients appearing in hospitals often had late-stage cases. But scientists needed to understand earlier progressions of the virus and its frequent mutations, and primate research became one of the most promising options in the search for cures and a potential vaccine.

Desrosiers’s SIV model allowed for research into the depletion of CD4T cells — a type of white blood cell known as a “helper T cell” that protects the immune system. Their depletion occurs when HIV is left untreated, and leads to the development of AIDs.

Understanding the basic subsets of a primate’s system across the course of an SIV infection allowed researchers to identify genetic therapies. Researchers would remove cells from the body, then inject genes into them to test if they would protect against the infection, and then re-insert the altered cells.

Several researchers praised the contributions Desrosiers made to the study of HIV. Some said his work was the foundation for their own research on the virus.

Paul Johnson spent decades characterizing cellular responses to SIV and reverse-engineering human techniques in primate models. Desrosiers, he says, played a “seminal role in the identification of simian AIDS.”

Welkin Johnson began his career under Desrosiers’s lab, eventually becoming a junior faculty member in microbiology at HMS. He first experienced the Center as a well-funded entity for national scientific pursuit. Research expanded to encapsulate studies on addiction, the herpes virus, spinal cord injuries, and Parkinson’s.

“It was immersive in the sense that you didn’t get the blinders on and just study this one molecule,” Welkin Johnson says. “You knew how to fit into the whole picture. I think that’s actually what made it a pretty special place for that kind of training.”

Desrosiers’s discoveries led him to the center’s top job, in which he served for 12 years.

His colleagues remember him as a giant in his field and in the center. But he declined to discuss his time at the NEPRC. Reached by phone, he asked that his name not be included in this story.

And he refers to the center’s closure, which took place months after he left his position, with anger.

“Harvard is never going to tell the truth on this topic so it will not matter whatever I say,” Desrosiers wrote in an email. “Harvard should be ashamed for closing such a leading biomedical research center and stepping away from their obligations as a leading medical research institution.”

The Whistleblower

The NEPRC, well-respected among researchers, had drawn activists’ ire. In 1983, 300 protesters staged a mock funeral outside the center, mourning primates they believed had unnecessarily died in medical experimentation. In 2000, a man staged a 100-hour sit-in in a cage in Harvard Yard to protest primate experiments, including at the NEPRC.

Organizations like People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals are opposed to primate research on principle: they believe animal testing is unethical, harmful, and ultimately unable to safely deliver scientific discovery. To this day, PETA brands the NEPRC, now long-closed, as “Harvard’s cruel monkey lab.”

The activists’ message never garnered much sympathy among HMS leadership. But toward the end of Desrosiers’s tenure, the NEPRC’s cultivated image began to deteriorate — particularly after a cage washing incident in 2010, which would become the first of a series of four deaths that would draw intense public and media scrutiny to the center. The deaths would push HMS to step in.

NEPRC had dealt with a public death once before, in 2003, when the Department of Public Health discovered a dead squirrel monkey on the side of the road 10 miles away from Southborough. Harvard had not disclosed the missing monkey to the public, though administrators insisted that they had notified the proper regulatory authorities. The bizarre occurrence made local papers, but coverage later fizzled out.

The next public death in 2010 was different: it was more gruesome, and it was not clear that the NEPRC ever intended to report it to regulatory agencies. During a routine cage washing, veterinary technicians put a cage into a 170-degree power washer, failing to realize that a cotton-top tamarin was still inside. A whistleblower alerted the USDA.

The monkey was eventually found to have died before its cage went through the machine, but the whistleblower’s report spurred a once hands-off Harvard administration to become more heavily involved in the center’s research. The intervention set into motion the discovery of serious long-term breakdowns in care under Desrosiers.

The initial investigation into the center after the cage washing death led HMS to replace the previous chair of the Division of Veterinary Resources. The new appointee, Matthew J. Kessler, soon noticed something strange — 17 rhesus macaque monkeys were inoculated with SIVnef off-protocol, meaning they were injected with simian immunodeficiency virus twice, rather than once as the research project called for. When he dug deeper, he realized the infected primates were also not euthanized on schedule.

Kessler reported the incident to HMS. The school began an internal investigation into the center’s practices, hiring two outside consultants and creating a subcommittee of the HMS Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

In an August 2011 letter obtained by The Crimson, HMS executive dean for administration Richard G. Mills wrote to regulators at NIH’s Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare. He outlined the findings of the HMS investigation: a long-simmering breakdown in the NEPRC’s veterinary care and its compliance with federal research regulations.

Blood and serum samples were collected from primates without authorization. Medical records were below acceptable standards. An official lied about the weights of certain primates to federal authorities. A veterinarian not accredited by the USDA signed certificates for primate shipments. Staff routinely failed to follow policies that included tuberculosis testing, use of personal protective equipment, and physiological support protocols for primate surgery.

“Management at the NEPRC failed to exercise sufficient control, and failed to be sufficiently aware of the problem,” Mill concluded.

Nancy Haigwood, then the director of the Oregon National Primate Center, met weekly with Desrosier and the other directors to discuss the national network of primate research. She says she was surprised when she learned of the animal care issues at Harvard. “I just remember that there was something amiss,” she says. “And that raised some flags for all of us thinking, ‘Well, gosh, Ron would have known that. Why didn’t he fix it?’”

In his letter, Mill wrote that HMS needed to exercise more supervision over the satellite facility. “HMS and the HMA IACUC must significantly improve oversight of animal research at NEPRC,” he wrote. His recommendation would precipitate major changes at the NEPRC.

The same month Harvard sent the letter to the NIH’s animal welfare office, Desrosiers stepped down as the head of the NEPRC. He was replaced by longtime NEPRC scientist Frederick C. Wang, who stepped in as research had been briefly paused to bring testing into compliance. But the NEPRC believed that research would soon resume without complications.

“There were no concerns shared with me that animal care and animal lives were in imminent jeopardy,” he noted.

The Unraveling

A month after Wang’s tenure began, a primate escaped its cage. A staff member caught it with a net, and during the subsequent imaging procedure, the monkey died.

It would be the first of three deaths under Wang’s tenure. He attempted to bring greater transparency to the center, reporting each incident to the USDA. The move ignited a public affairs nightmare for the University, as the Los Angeles Times, Boston Globe, and New York Times all noted the deaths at NEPRC. As Harvard’s name and brand became increasingly connected to the faraway facility, administrators repeatedly found themselves explaining the incidents to the media.

And inside the NEPRC, a reckoning continued. The public deaths gave way to the discovery of even more systematic violations of animal care procedures, perhaps dating back years.

“I quickly realized the culture and operational problems left by the previous NEPRC leadership team were much deeper than I expected,” Wang wrote in a statement to The Crimson. “This was a big surprise and hard for me to believe.”

The second high-profile death occurred in December 2011, when two squirrel monkeys were found dehydrated. One was subsequently euthanized while the other survived.

When the primate died, its body wound up in the care of Andrew D. Miller, a primate pathologist at the facility. Miller, who was studying the effects of high sodium levels in monkeys’ blood, observed that dehydration was listed as the cause of death of 14 squirrel monkeys at the center between 1999 and 2008. And he noted that the squirrels’ deaths had apparently not been disclosed to any oversight bodies.

“I would presume that this most recent animal should be reported; however I would doubt that any of the animals on this spreadsheet were reported in the past,” Miller wrote in his email to Wang, which was first shared with the Globe and The Crimson in 2015. (Harvard confirmed to the Globe that the IACUC had not received reports on the deaths.)

Wang, shocked by the data, reported it to HMS in 2012.

Yet at the time, the public knew nothing of Miller’s numbers. The Crimson Editorial Board penned a staff editorial in 2013 titled “Confronting Cruelty” in response to the one instance of primate dehydration they knew about. “We are enormously disturbed by the incidences of animal cruelty uncovered in Harvard labs, and believe that HMS should be held accountable for its alleged negligent handling of lab animals,” they wrote.

That February, a third primate died when a diabetic cotton-top tamarin was briefly deprived of water. Again, Wang reported the incident to the IACUC and the USDA. Again, coverage of the center — and scrutiny of Harvard’s responsibility — intensified. “Deaths of Harvard lab animals stir criticism,” read one Globe headline. “Third monkey dies at Harvard research center,” read another. The piece quoted an interview with then-HMS executive dean of research William W. Chin, who said he and Harvard officials first became aware of “deficiencies” with management after the deaths of monkeys in summer 2010.

Wang’s appointment the next year, as well as the creation of a six-member team to audit the NEPRC’s work, were designed to address those concerns, Chin told the Globe. He chalked the subsequent deaths up to the fact that it would take time for reforms “to take hold.”

“Understandably, the public media was confused about why such a seemingly pristine primate center suddenly had three animal deaths during my short tenure,” Wang wrote in an email. He added that he was not able to disclose to the media any evidence “for the depth of past problems and cover-up at the primate center.”

Haigwood says that the seven other centers dealt with unfortunate but occasional primate deaths during their history. But she stresses that the other centers and their directors had long been proactive with media and the public — a strategy she described as getting “ahead of the press.”

“And my understanding was that Harvard was not interested in doing that,” she says. “They did not want to be in any way transparent.”

On March 1, 2012, Wang stepped down from his post leading the center, citing “personal and professional” reasons. The Dean of Harvard Medical School, Jeffrey S. Flier, praised Wang at the time for instituting a “transformative culture of transparency to the NEPRC.” The Crimson Editorial Board amended its opinion, acknowledging the unfortunate nature of recent deaths but praising the Harvard administration for its “vigorous action.”

While Wang wrote he was willing to accept responsibility for any mistake on his own watch, he alleged that HMS continually insisted that he remain opaque with the public.

“I left the NEPRC when I felt this culture of hiding mistakes coming from HMS leadership. Using transparency to build compliance and public trust was being blocked by a private institution accustomed to controlling and limiting public disclosures,” Wang wrote.

“I could fix the culture at the primate center, but I could not change the culture of HMS leadership,” he wrote.

Two years after Wang reported the 14 primate deaths under Desrosiers, Miller published a study on the data, establishing a link between high sodium levels in monkeys’ blood — often an effect of dehydration — and brain lesions. Miller’s paper chalked the sodium levels up to preexisting illnesses in the monkeys.

But in 2016, Miller and his coauthors retracted the paper — apparently because they now had evidence that suggested Wang had been right to find fault elsewhere.

“Further evaluation of clinical case materials which were not available to us at the time of submission and publication of this work suggests that a subset of the animals described in the paper may have had inadequate access to water,” the retraction notice read.

Miller wrote in an emailed statement that the team’s paper “did not determine why the animals became dehydrated as there are potential causes that are not due to negligence.” But Wang remains convinced that the deaths were caused by misconduct, and that the 2014 paper obscured animal care issues that had mounted long before his term.

Despite Wang’s resignation, HMS leadership sought a path out of the controversy. The school developed new reform efforts: meeting monthly with then-President Drew G. Faust, sending a Blue Ribbon Panel of experts to investigate the facility, and instituting a new interim director, Paul Johnson. (Faust declined to comment for this article.)

For one senior HMS official, who would later be involved in the NEPRC’s closure, the Blue Ribbon Panel’s review revealed that “we were well on the way to addressing the things that needed to be fixed.”

“We changed the leadership. We had brought in some additional people and processes. We made it clear that the Medical School was going to be more involved, rather than just signing off on the grant,” he adds.

The center’s future, however, ultimately lay with University leadership. And as the deadline to renew the center’s grant with the NIH approached, HMS officials were met with silence.

“It was, I think, very nerve-wracking, increasingly as months went on to not have a response. And that was highly concerning to me,” Paul Johnson says.

The University at large had been combating financial concerns and was instituting austerity measures in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Yet the panel had explored several financial paths forward and concluded that “the cheapest, most cost-effective option was to invest modestly in the primate center,” Johnson says.

By October, the panel decided the primate center should be “renewed and refreshed.” Affiliates hoped research would resume in full force.

But in April, Harvard Medical School came knocking on the NEPRC doors. The University had officially decided to close the center.

The Shutdown

The once-bustling ecosystem of NEPRC — more than 1,700 animals, 200 employees, 30 faculty members, and abundant grants — needed to be dismantled. The painstaking process took more than two years, as staffers and monkeys dispersed across the United States. A portion of the property was demolished, while another section remained, later to be repurposed as Harvard’s Book Depository.

Researchers were shocked by Harvard’s decision to shutter the facility, which had pioneered biomedical research in non-human primates. Opportunities in primate research were few and far between, with many of the center’s world-renowned researchers leaving for appointments across the seven remaining centers.

“There were limited places that people could go, and under the circumstances, there was a lot of help offered to try to make homes for other investigators,” Haigwood says.

“And these are our friends,” she adds. “We all know each other.”

At the time, HMS cited financial constraints. An announcement posted to the school’s site in April 2013 stated that the NEPRC’s leaders had “successfully addressed operating issues with input from the NIH and other governing agencies” by the time of the closure.

The announcement described the closure as “extremely difficult in light of the groundbreaking research that has been conducted at the Center over the past 50 years.”

The announcement pointed to rising uncertainty around federal funding, compounded by Harvard’s own budgetary limits, as reasons why HMS decided it was not worth it to reapply for a five-year federal grant that provided significant support to the center.

“You know how things work. That’s what we decided to say,” said the senior HMS official. “Clearly, the statement was not designed to explain fully the complexity of the history in the background and the university.”

Asked for comment for this article, HMS spokesperson Laura DeCoste referred to the school’s 2013 announcement. She wrote that “HMS reaffirms its longstanding commitments to the welfare of all animals in our care and to animal research, which remains indispensable for finding new treatments, preventions, and cures for diseases affecting both humans and animals.”

For Welkin — who left his appointment on Longwood for one at Boston College just before the center’s closure — more questions remain than answers. Internally, the closure arrived as national researchers explored the potential of further collaboration.

“When I left, there was every reason to think the primate center was going to continue,” Welkin Johnon says. “It seemed like there’d been a bit of a crisis that didn’t really involve the science, and involved management of some kind,” he adds. At the end of his time at the NEPRC, he remembers affiliates coming in from Longwood to give speeches about the transitional nature of the center. They pitched a generalized plan to work around the media scrutiny and incidents — for the broader pursuit of science.

“I think that my impression is that maybe that boot kicked open the hornet’s nest,” Johnson says. “You know, was there sloppiness? Were people not following the animal protocols? I don’t know if you know the outcome of that. It just seemed that things sort of snowballed after.”

For Haigwood, the closure was a shock to her and the national network.

“Paul did a great job, and then to be told, after he’d done all this work that, ‘no, we’re closing it anyway,’ that's when the big shot came,” Haigwood says, referring to Paul Johnson, who led the center up to its closure. “That — that was just appalling.”

Haigwood noted that after the decision, they asked if the money would be distributed across other centers to adequately care for the animals. The answer was no. “There was definitely a hit to all the centers that took animals. And as far as I know, almost all the centers, if not all, took some animals,” she says.

“Lots of people were still dying from HIV, and so people were very invested in their research. To have that taken away was very emotionally draining,” Paul Johnson says.

Scientists dispersed to other primate centers, finding new appointments at universities across the U.S. They brought their research with them. Harvard no longer held a national hub for primate research on HIV, cancer, addiction, and neurodegenerative disease, the areas in which the NEPRC had historically excelled.

NEPRC researchers contributed to the first primate models for progressive neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease, which led to novel treatments for Parkinson’s. Researchers also discovered oncogenic herpesvirus, a type of herpes that can lead to cancer and disruptive cell growth. It was at the NEPRC that researchers first demonstrated conclusively that AIDS is caused by a virus — and that it was possible to protect against the disease with a vaccine.

The closure was celebrated by animal rights organizations like PETA, which continues to campaign against non-human primate research at Harvard. At the time, Time Magazine wondered: “Are lab chimps becoming a thing of the past?”

All seven other national centers remain in operation today. Their research — into conditions from AIDS to addiction — continues, powered by NIH grants and private sponsorships.

Only Harvard decided to pull the plug. Questions regarding the center’s closure — and the loss of its research — still plague the minds of old affiliates. And at least one mystery from after the closure still lingers: the strange deaths of the six cotton-top tamarins at the Oregon Zoo, one of the last incidents at NEPRC to make headlines.

In a memo to the director of the Oregon Zoo, a veterinarian wrote: “Unfortunately, as much as we would like, we will never know the specific cause of death of these tamarins.”

Before the NEPRC’s bustling campus became a depository for little-used books, before its researchers scattered across the country, before hundreds of primates were packed into boxes and transported nationwide, scientists were left to grapple with a sense of surprise and loss.

There were “lots of emotions going around,” Paul Johnson says. “Shock was certainly one. I think most people did not anticipate that Harvard would make the decision to close the primate center. You know, it came as a shock to me, and, frankly, a loss of family,” he adds.

“It was the premier center, is one of the very best, and looked up to greatly,” Haigwood says. “And I think it was a huge loss for Harvard — and a big mistake.”

Correction: November 9, 2025

A previous version of this article incorrectly described former New England Primate Research Center director R. Paul Johnson as a “foreign virologist.” In fact, Johnson is a physician and immunologist.

—Magazine writer Jack B. Reardon can be reached at jack.reardon@thecrimson.com. Follow him on X @JackBReardon.

—Staff writer Ella F. Niederhelman can be reached at ella.niederhelman@thecrimson.com. Follow her on X @eniederhelman.