Field Notes of an International Super Spy

Initiation

August 23rd, 2021, 1600 hours. John F. Kennedy Airport, New York City.

I clutch my golden ticket — an American passport — and pass through Customs and Border Protection with ease. After a decade of fieldwork in China, America welcomes the return of its most famed international super spy. Sino-American tensions are running high. Both countries could use a diplomatic agent, and I am the woman for the job. I am dispatched to an elite preparatory boarding school in Western Massachusetts, rife with high-profile targets for cultural investigation. My mission: to infiltrate their homes during school breaks and observe the populations of America. To learn everything about them. But they must know nothing about me.

Infiltration

Espionage is a delicate affair. It appears that access to the inner workings of American households can only be acquired via one avenue: friendship. My freshman year at Deerfield Academy, I observed, with much confusion, how friendship often commences with the transgression of boundaries. The way I tarry into my friends’ dorm rooms even when they are not there, swiping a snack or two, surveying their clothing options and surreptitiously dashing off with three sweaters to try on. Openly admitting this would probably blow my cover as a foreign agent, but frankly, I’d observe that our system of garment-sharing is a bit communist, too. Or take the times that I’ve returned to my private quarters after school to find one of my friends nested under my covers, knocked out cold. Subject to such breaches of security, I conceal my files and spy gear well. Every boundary crossed is a point scored for me, and I became quite good at this game. When my targets finally pop The Question — What are you doing for [insert American holiday]? Can you go home? — I know I’ve got them buttered up. I’m on the inside.

During Deerfield’s breaks, my real covert operations commence. All the rules of the game change. Living in someone else’s home always necessitates a certain vigilance, no matter how many times I have done this. I know this from my training: in someone else’s home, the conceptual divisions between “yours” and “mine” reassert themselves — your house, your property, your rules. Eggshells crackle under my feet the moment I tiptoe past the front door.

I hold myself to the highest standards of spy conduct. I am sure to collect the hair that has accumulated on the wall of the shower, sure to wipe down the trails of water I’ve tracked into the bathroom, hair sopping wet. I try a little harder to eat all the food that I’ve been offered, dashing to rinse the dishes. I put things back where they belong. I remember to always clean up after myself. I stop the microwave before it’s done, close the fridge door before it beeps, shut the lights when I leave the room, turn off the faucet when I’m brushing my teeth, silence my alarm after the first ring, put on my shoes with haste. I speak a little more kindly, listen a little more intently. I observe. I am sharp, firm, unwavering. So why can’t I be the same way when I return to my own home? Why is it that as soon as I return to Shanghai, I melt?

On Dogs

A rather unnerving observation: of the seven American families I have investigated, all own dogs.

My upbringing in a no-dogs household left me ill-prepared for this understudied dimension of fieldwork. On sleepless nights, I tossed and turned and schemed. How would I allay the suspicions of the family’s most shrewd and loyal defender, the family dog?

Three years ago, I conducted a two-week anthropological study into the Cho family of San José. Every night without fail, their Yorkshire terrier — Chubi — sweet and small as a snowball, would snuggle into my sweatshirt as I occupied his spot on the couch. His cuteness was deceiving; by the conspiratorial glint in his black eyes I knew he was onto me. As Socho (short for Sophia Cho) and I lay in her bed, having some heart-to-heart, Chubi perched on my sternum, cocking his head, nodding to what we were saying, laying his paw to my rising and falling chest. Heart to heart to paw. Chubi, the very best boy.

I was particularly intrigued by the unconditional dedication my targets exhibited for these creatures. I was even more intrigued by their reciprocation of such dedication. Thus, I infiltrated family walks and hikes, seeking more insight into interspecies dynamics between man and dog.

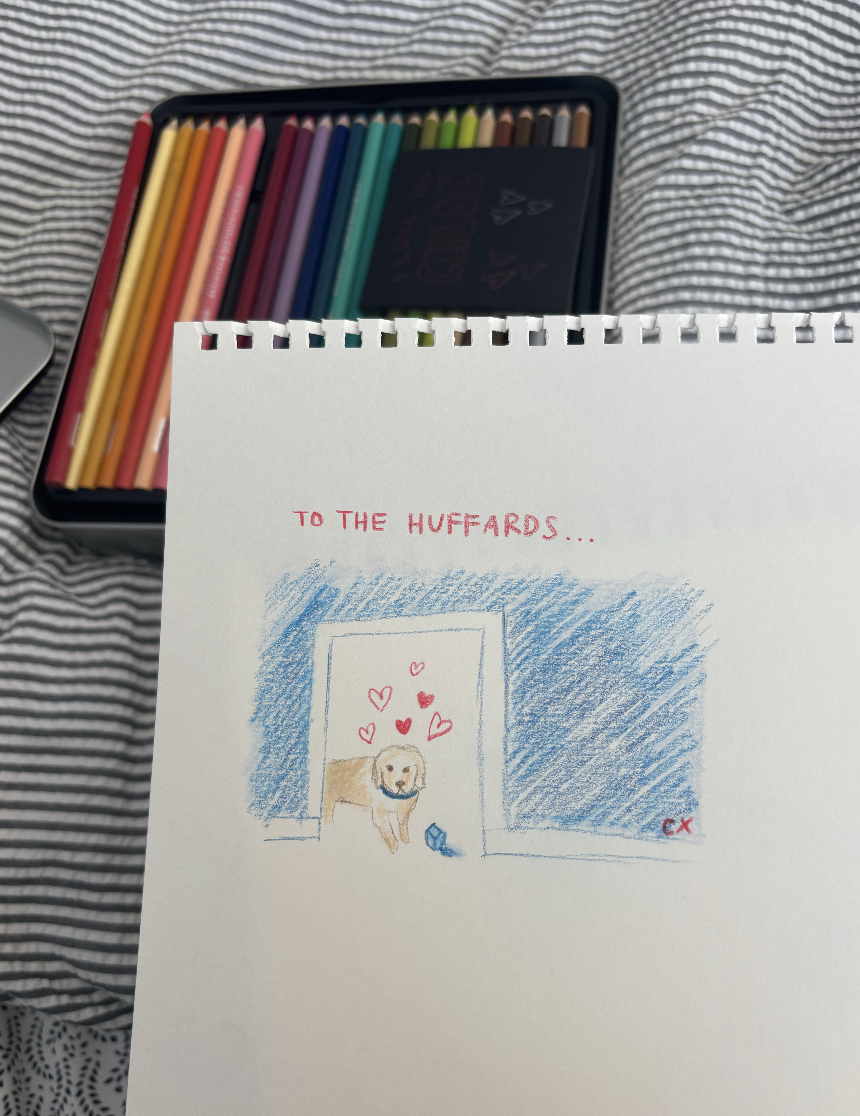

This winter, during my sustained investigation into the Huffards of Greenwich, Connecticut, I befriended their strikingly anthropomorphic golden retriever, Blue. Blue was well-versed in the human practice of haggling, employing his large brown eyes to swindle me out of my ice cubes every morning. Blue grew up a favorite child, with toys any pup would envy — yet he was hopelessly, singularly devoted to his ice cubes. Polar Cow, the Huffards nicknamed him.

On walks, Blue would stop to lick every piece of the fresh, crunchy ice we passed, curling his tongue over moss and grass. Watching him, I felt distracted from my mission. I found myself thinking about my own family instead. For us, walks are taboo. My father suffers from a chronic lung disorder, which has rendered walks together a relic of my childhood. Despite my sister’s persistent requests, my family remains staunchly anti-dog. Our groceries get delivered to our front door. We have nothing left to walk for.

Careful not to let my personal circumstances tamper with my operations, I resolved to fold these feelings away. I kept them in a suitcase, neat and small. I carried it to every home I investigated.

Family Cars

Deep in the jungle of American suburbia, the lone wolf dies, but the pack survives. Their protector? The family car.

Every family car has unique responsibilities. Socho’s family drove their Tesla all across San José to introduce me to their favorite bingsoo and Korean fusion restaurants. Emily’s sister Katie drove us to the beach where the sand whipped my skin as I watched the crashing Montauk waves. All I could smell was salt. Anneke’s car, an inherited Volvo, boasts furry white covers on its front seats. We could never tell if the fur — floating in the car, sticking to our bodies, proliferating constantly — was from the covers or from her dog, Amby. “Freak fuzz,” we named it.

“Isn’t it pretty?” Charlotte, a surprisingly adept driver and proud Chicagoan asked me. Every three or four minutes, she nagged me to look out the window at the Chicago skyline. “You should come to Shanghai,” I respond.

There is no place in Shanghai more than five minutes away from public transport. I never learned how to drive; taxis were always at my fingertips. Why teenagers in the movies so desperately yearned for a car continually eluded me. But I understand now: in suburbia, travelling by car is a fact of life, as intuitive as breathing. You cannot live without it. Yet my investigations have revealed to me that driving itself is an expression of love.

Once, braving snowed-over roads, Edie drove us home from a Super Bowl watch party. Four of us rode in her grandmother’s Subaru, which we lovingly refer to as the “BRAT-mobile,” for the neon green stripe running across its body. My chronic motion sickness and lack of a driver’s license renders me Edie’s perennial passenger princess.

The distinct precariousness of my situation hits me as I fixate on the breathtaking foliage from the window. The BRAT-mobile parts the fallen leaves, revealing the unpaved dirt-roads on the way to Deerfield. If not for Edie and for the BRAT-mobile, I would be powerless, immobile. I have no means of traversing these foreign terrains on my own. I have no means of reciprocating her acts of service. Edie doesn’t hold this against me. In fact, to every other passenger who tries to get in the front seat, she quips, “We don’t want Chloe to throw up now, do we?” To be loved is to be considered, I think to myself. In the BRAT-mobile I never need to call shotgun. It is my place and I know it — a home, however transient.

The Confession

I’m no international super spy. I spend my breaks infiltrating the families of my friends because my own is a 16-hour flight away. I once tried to make myself small in my friends’ homes, but my debts to each of them are greater than I can articulate. More than anything, every single home I visit broadens my conception of what life could be. I stanky-leg around the kitchen with Emily’s dad, a fisherman and lover of challah and fried rice. I examine the distinctive decor that adorns Edie’s house, the meticulous work of her mother. I study photographs of Anneke and her family, the passage of time signalled by her father’s changing beard.

I am in love with this intricate investigative job of learning about other people’s lives. These houses, full of history. These families, full of life. All of a sudden, my world doesn’t seem so small, and I can see a future for myself. House hopping has enchanted me with the full range of human experience, of how the smallest of choices leads us to the most different of lives.

I keep writing about other families, other stories. I am dancing around my own. For as long as I can remember, I have refused to write about my family. I am fascinated by the stories of strangers — Soviet poets, Progressive-era utopians, Jordanian protesters — but I refuse my own. I hope to study history in college, but my own history terrifies me. History is heavy, and I prefer to float, waltzing between truths and pausing in my footwork only to pick those palatable to me. I thought true agency came from the absence of such weight. This makes me the most unreliable of narrators, and I’ll admit it. I carry my suitcase, full of feelings, to every home I visit. It’s about to burst. I feel the zipper, quivering.

When I moved to America alone, I convinced myself that I was the person who molded myself from these new soils — solo dolo. I forgot what I was given, believing that this life — this language, this love, this luck, this luminous light — was all my own. “What I was given,” I wrote. My passive voice obscures the subject of my sentence. I am still conjuring the courage for this confrontation. What I know is true: I hesitate to pen the story of my family because my narration lingers in half-truths. The other half is sitting at our dinner table, sipping lukewarm water, waiting for me to return a text.