Turning Back the Page at Boston’s Antiquarian Book Fair

At the Hynes Convention Center, books, protected behind glass cases, are displayed under showroom lights. These aren’t just any books. On a shelf slightly below eye-level, a copy of Shakespeare’s Fourth Folio from 1685 stands above the rest — at least two times taller than any other book on the shelf. An intricate gold-colored border encases a portrait of Shakespeare, staring back at passersby.

The asking price? $225k.

Unusual finds like this one are a regular at the 47th Annual Boston International Antiquarian Book Fair, a three-day event showcasing a rare collection of manuscripts, first editions, ephemera, maps, and autographs. Like the international books on display, attendees travel from around the globe to nerd out over historical preservation and find hidden gems for their personal book collections.

Despite the intimidating price tags, book fair-goers greet each other with an air of eagerness and curiosity. Vendors call out names of familiar faces, their tables surrounded by fellow book enthusiasts.

Javier Ortega assembled a sizable crowd as he presented his Shakespearean Folio to attendees. The second-time vendor at the fair also had a $17k Harry Potter edition and a signed copy of Mark Twain up for sale. As guests flow past his booth, he explains what makes events like this remarkable.

“It’s just a special trade full of very special people,” he says.

Right across from Ortega, Noah Peterson displays a geography text from 1545 showing America as its own continent for the first time. Explaining its significance, he says, “You’re literally picking up and finding history in the craziest places.”

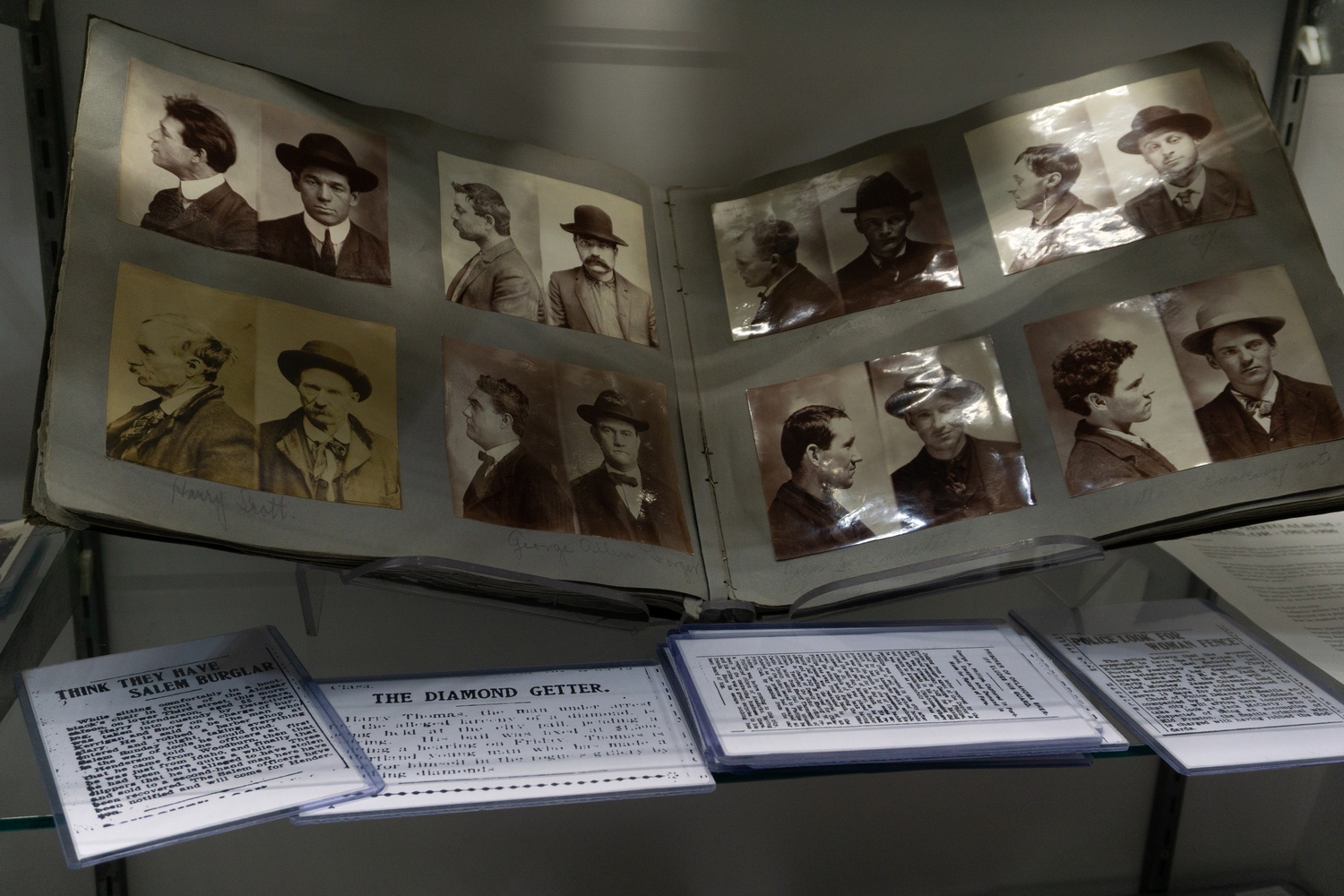

Book vendors and collectors at the Antiquarian Book Fair speak passionately about every book in their collection to anyone who asks. Ian J. Khan, a vendor, encapsulates his own niche materials as “esoterica” — dealer-speak for the highly specialized lore that he typifies as “challenging material for any period.” His table is littered with materials spanning witchcraft, occultism, and demonology. “The more uncomfortable it makes you to hold,” Khan jokes, “the more likely I am to be interested.”

Booths like Khan’s don’t necessarily fit the image of what one might expect at an antiquarian book fair. Not every vendor offers exclusively archaic literature, nor does every attendee fit the archetypal “elder book collector” stereotype. Contrasting the tables stacked with centuries-old manuscripts, a new crowd peruses the booths — younger, phone in hand, tote bag slung over shoulder. Among books with centuries of history, many attendees are not yet 30.

For younger folks like Ru Jia, a graduate student who studies architecture, attending the book fair was a spontaneous decision. “I was just scrolling on social media, looking for fun events to go to on the weekend,” she says.

Michael Jiang, a second-year Ph.D. student who attended with Jia, is interested in studying the past. “I’m very drawn to the idea of looking at artifacts through history.” With a smile, he adds, “Now I’m here. I really enjoy it.”

Mely DeLeon, a veteran attendee, noticed that “there are definitely more younger people” this year. Upon consideration as to why this is the case, DeLeon explains, “I do think it’s tied to a rise in fandom culture and stan culture now, where people are very interested in collectibles.”

Trends like these appear to encourage new habits among a new, younger generation of book collectors. Ruby Rice, a lover of old fairytales, sees these generational differences as a divergence in consumption habits.

“I feel like in our generation, there’s kind of a divide between minimalism and maximalism, where people will spend the money to collect these rare items because it’s their passion, but a lot of people want to be able to live that nomadic lifestyle,” she says.

Looking around, the book fair seems to have taken notice. At this year’s conference, not all of the booths orient their eyes to the past. One row along the wall presents booths dedicated to contemporary literature. Another stall features a first edition of “A Court of Thorns and Roses,” a popular fantasy series first published in 2015.

The excitement of younger generations at the book fair raises a question at the heart of this year’s event: in an age of digitization and the movement away from book collecting, why do young people still seek out the texture and scarcity of old texts?

Sarah-Jane E. Sellers, a self-proclaimed “Northanger Abbey” enthusiast, noticed how young people, while enthusiastic at the conference, were not the ones purchasing books. In her experience at antique book fairs, the “money thing” — the “thousands of dollars” required to buy old books — excludes younger people.

In her eyes, digitization might help bridge the gap. “I think a digitized version of a first edition lets people study it without having to be rich enough to purchase it or have the connections to see it in person,” she says.

But at the fair, everything is physical. There are no QR codes, no eBooks, and no PDFs in sight. For Richard Li, who had just finished admiring a historical copy of “Moby Dick,” this focus on physical collection helps foster an appreciation for preservation in a new generation.

“There’s actually things beyond the book contents, like the aesthetics or the material feelings when you touch the books,” Li says. “It’s really different from reading electronic books.”

Somie Kim, a children’s book author, believes that focusing on physical texts in a place like the book fair helps provide an emotional connection between author and reader. “Coming here and seeing all these youth when we are moving into digital reading now,” she says, adding, “I’m still glad to see people being involved in physical books.”