The War on Science

To the six-year-old version of me who looked into a microscope for the first time, the notion of an American president launching a “war on science” — as President Donald Trump has done — would have been just about as ridiculous as an American president announcing that we were going to exterminate bald eagles or abolish the hamburger.

In essence, science was right up there with McDonald’s as the most American thing I could think of.

Little surprise. For a school project, I once asked my dad why he came to the United States. “For the science,” he told me. And then, as an afterthought: “And for a better life, obviously.”

My parents left China to earn graduate degrees in the biomedical sciences, and immigrated to America — where I was born — on H-1B visas so that they could work in labs. For many years, we lived in housing subsidized by Weill Cornell Medicine. My dad’s faculty grant is paying for my degree in molecular and cellular biology. It’s no wonder that I see science as fundamentally American: for my family, it is more than simply inquiry, pushing the bounds of human knowledge. It is a means of citizenship, a roof over our heads, and a good education.

And yet, from the beginning of his term, Trump has crusaded against science: he has called it a broken system not up to a “gold standard,” slashed scientific agencies, terminated grants, defunded laboratories, and used executive orders and financial threats in an attempt to bully the scientific and academic establishment into producing science that aligns with his administration’s values. He has railed against international students, like my parents once were. He has derided science, and the people and universities that produce it, as elitist, dangerous, and ideologically charged.

It is a strange thing to see. It is a dismantling of the scientific enterprise, of what I grew up to understand as the most American of pursuits, by an American president.

***

I grew up in a laboratory and I pretty much never left. In elementary school, my dad would pick me up and let me do my times tables at an empty bench. Sometimes, when I finished my homework, he would hand me a pipette and a conical of water and tell me to “discover something” while he disappeared behind the door of a tissue culture room to make the real science happen.

I discovered nothing by lining up water droplets the size of my thumbnail on a sheet of paraffin film, but each one might have been its own ocean, for how much they mattered to me. Every so often, my dad would come by to check on my progress. He’d leave me with a new box of tips and adjust my grip. When my hand got shaky, he showed me how to use the other hand to stabilize it.

Even then, my dad and I weren’t big talkers. He’s not the kind of person who likes to hear about friend group drama or new music. But in each water droplet I pipetted under his guidance was a kind of communion. It was as if I was catching up to him, starting on the same road he had taken when he left China: a road to America, a road to science, a road to progress.

***

Now, I am in college, and science is a lot more complicated than pipettes and water droplets. It is mornings wrestling with gel rigs and skipping lunch to transfect cells and late nights poring over data trying to make it all make sense. When I hold a pipette in my hand, I rarely feel like I am “discovering” something the way my dad always told me to — I feel like I’m trying not to destroy hundreds of dollars’ worth of reagent instead.

Last summer, I called my dad most afternoons on the twenty minute walk from my lab at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute to my summer sublet in Fenway. My Mandarin has lapsed since I left for college, and he doesn’t always get what I mean when I say it in English. But I can still ask him about why he thinks my cells aren’t fluorescing under the scope, or how he thinks I should design an RNA guide for a CRISPR experiment, and we can talk for hours.

At the end of one of these conversations, somewhere on Brookline Avenue, my dad got uncharacteristically quiet.

“You’re doing it,” he told me in Mandarin.

“Doing what?” I asked, half-distracted. I was scrolling through a spreadsheet of candidate genes while I waited for the light.

“Discovering something,” he said.

“I’m hardly discovering anything,” I told him. “I’m just doing what my boss tells me to do and trying not to ruin everything.”

There was a pause. Then his voice, crackly over the line: “You’re doing what I came to this country to do.”

That summer, we did not talk about President Trump’s assault on American science, even though my university stood at the forefront of his attack and he was applying for NIH grants he didn’t think he could win. Instead, in the space between lab and home, we talked about my work and his work, about cells and reagents and never quite having enough time or expertise to interrogate the questions we really wanted to answer. Even now, even over the phone, science is the language we share.

But there is a war on science in America.

That much seems irrefutable to me: more than $5 billion has been cut in grants across the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. Graduate students are being turned away at Harvard and elsewhere because budgets are thinning and studies are shuttering before their time. Jobs have been cut in the thousands at federal agencies like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Environmental Protection Agency. Next year’s White House budget proposal would cut funds to the National Science Foundation by 56.9 percent, and the NIH by 39.3 percent. A survey by the journal Nature found that 75 percent of researchers polled are considering leaving the country.

It’s a truth that lives in the back of my head when I consider what I’d like to do after college. There’s no way of knowing what the scientific landscape will look like in May of 2028 — just months before the next presidential election. I hear conflicting advice from mentors and professors: some say to look elsewhere for a career, others are confident that by the time I graduate, this will all have resolved itself. I’m still not sure what to think — some days, I let myself imagine that it will all blow over. Other days, I consider becoming a consultant.

Regardless, the United States, which my dad, as a college student in China, saw as a beacon of advancement — for the world and for himself — does not seem quite so appealing anymore.

***

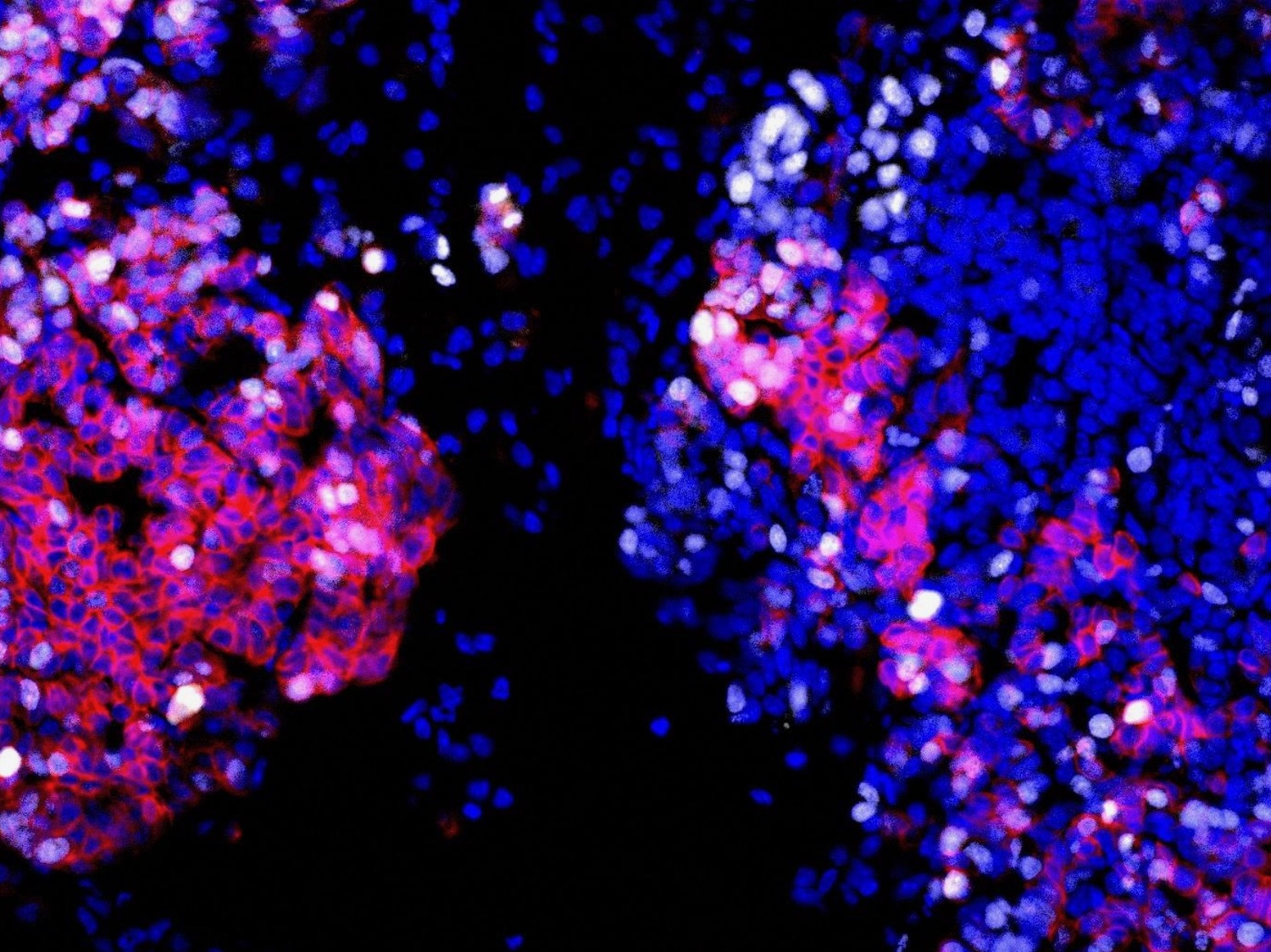

When I was six years old, my dad sat me in his lap so I could look into a microscope for the very first time. The slide was pink with cells, teeming with purple nuclei.

If there was to be a war on science, I didn’t know about it yet.

All I knew was that there was a world in miniature on the microscope slide, waiting to be discovered.

—Associate Magazine Editor Sophie Gao can be reached at sophie.gao@thecrimson.com. Follow her on X @sophiegao22.