Scientists and the Face of God

I don’t recall the quote exactly, but it went something like this: “One either becomes a scientist to find the cure for cancer or to find the face of God.” Only in hindsight have I come to see that Harvard molecular genetics professor Andrew W. Murray was joking. But as a freshman sitting in Life Sciences 50, I took his comment very seriously. I dreamed of becoming a researcher.

I did not believe in God, but I wanted to see his face.

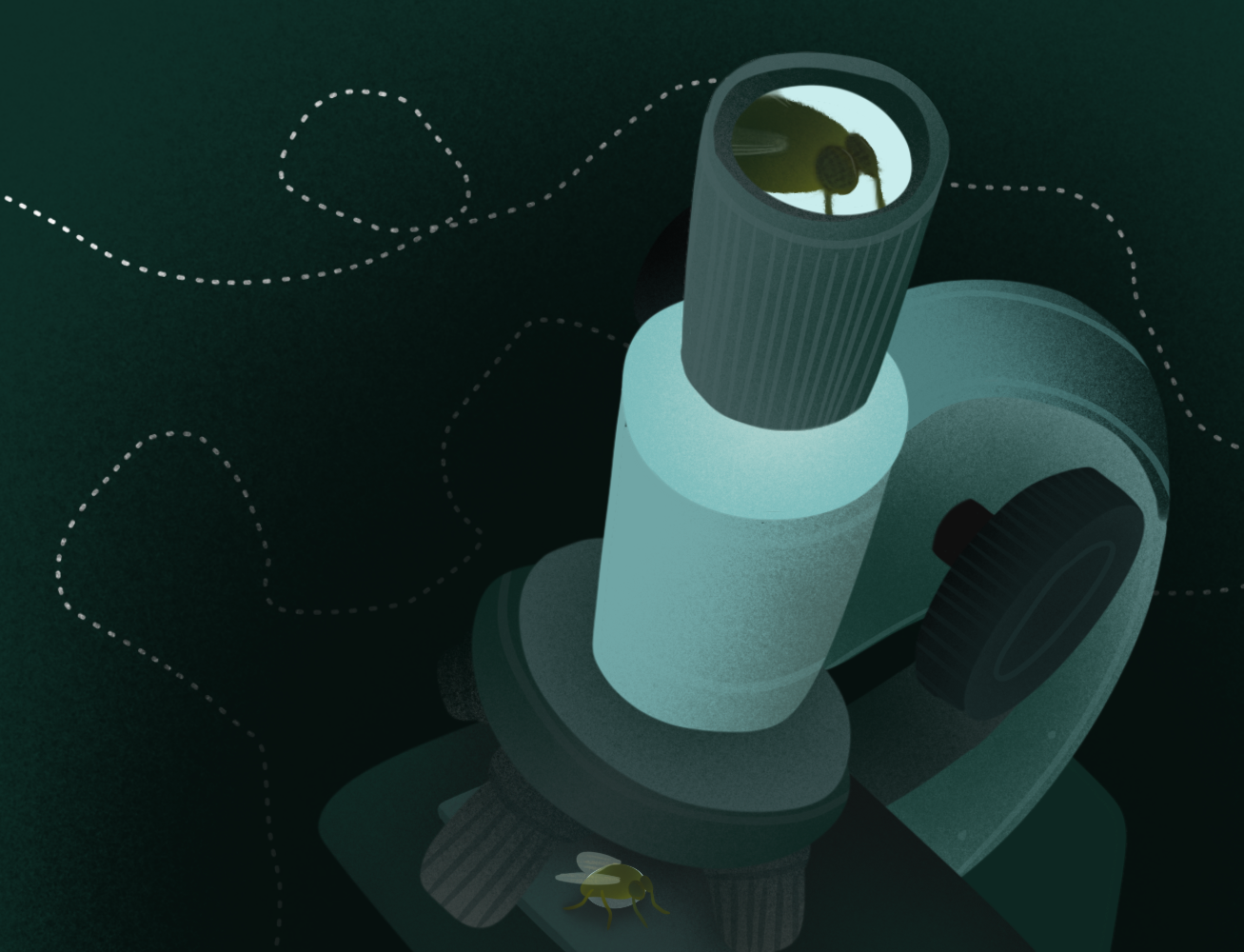

Sitting before a bench microscope less than a year later, I carefully examined the corpses of dying fruit flies. It was the summer before my sophomore year, and I had been awarded a fellowship to study Entomophthora muscae, a microscopic fungus capable of killing flies. As fungal ooze flowed out of a fly’s extended proboscis, I couldn’t help but think about Murray’s comment. The fly’s eyes were red and its body wrinkled. Was I looking at God’s actual face?

Of course, I am only writing in metaphor. I have never understood science to be a means toward divinity. When Murray spoke of God, I always thought about truth. But as I watched the fly’s magnified body before me, I found the face of truth to be ugly. Looking at the fly, I saw myself.

***

An adult fruit fly’s genome carries approximately 14,000 protein-coding genes, 63 percent of which are present in human cells, too. At a chemical level, the similarities between us are even more striking — we are made out of identical molecular building blocks, and our bodies are governed by the same flow of biological information: DNA goes to RNA goes to protein. The same is true of all organisms. Primates and dipterans, we are truly not that different.

When I first joined Molecular and Cellular Biology professor Carolyn N. Elya’s laboratory as a freshman, I wasn’t thinking about these similarities. I first met her at a chalk talk organized by the Microbial Sciences Initiative near the end of the fall semester. Most attendees were professors and graduate students. My best friend from LS50 and I were among the few undergraduates present. She and I would frequent the events organized by the MCB department: the Thursday Seminars at Northwest and the Friday Science Talks at the Biological Laboratories. Like most other LS50ers, the two of us were eagerly looking for principal investigators to become our mentors; there was a clear, even if tacit, assumption that we would all be doing research over the summer. We were all in the process of becoming scientists.

I remember watching Elya explain her research. She walked us through the infectious process with conceptual elegance: How an Entomophthora spore will penetrate the cuticle of a fruit fly and multiply inside it. How it will breach into the fly’s brain to manipulate its bodily movements. How at dusk on the fourth day of the infection, the fly will succumb and the fungus will kill. The biology of the process was fascinating. At the end of the chalk talk, I asked Professor Elya if I could join her lab. Much to my excitement, she said yes.

As I inspected infected fruit flies under a compound scope that summer, I found it hard not to think metaphysically. As an aspiring biochemist, I would understand the dying fly’s behavior as an outcome, the net sum of complex, molecular processes. Eventually, though, I started to think about my own behavior, whether it could also be reducible to similar mechanisms. Another one of Professor Murray’s aphorisms came to mind, this one a quote from the French scientist and Nobel Laureate Jacques Monod: “What is true for E. coli is true for the elephant.” The conclusion seemed inevitable, then. What was true for the fly must be true for Andrés.

The problem was that it didn’t feel that way. I believed in science, but I also believed in agency, in free will. To think of myself as a machine driven by chemical reactions beyond my control felt outrageous. I knew myself to be more than just a body. I wanted to believe that I was also a mind.

In a preface to the 50th anniversary edition of his 1974 essay “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?”, philosopher Thomas Nagel points to this source of tension, writing that “the reality of consciousness implies that the physical sciences give an incomplete description of the natural order.” Nagel argues that a purely material and objective account will never fully capture an agent’s subjective, conscious experience. In light of this, science may help us understand an agent, but it will never help us know what it is like to be one. Reading Nagel, I came to consider that I had only seen truth’s silhouette. To see truth in the eyes, it appeared that science would be insufficient.

***

The following semester, during my sophomore fall, I had a great conversation with a professor interested in the biological basis of individuality. Inevitably, our conversation turned to a discussion on agency and free will.

He explained that the concept of agency isn’t central to the work of biologists. “In the lab, we work to understand the mechanistic basis of brain processes, yes. But such an understanding is separate from the concept of agency,” he continued, his words spoken fluidly and without hesitation. “It doesn’t matter if the organism that we are studying is an agent or not.”

“But doesn’t that bother you?” I interrogated.

“I mean, it’s something I choose not to think about.”

“But how can you not think about it?”

He looked at me. “Well, I think I can know that my behavior emerges from molecular interactions.” He brought his hands together, interlocking his fingers. “But that doesn’t affect how I go about my day. It doesn’t really change how I conceive —” and he stopped to think, I remember, even if just for an instant. “No, not conceive. How I feel myself free. It doesn’t really change it.”

And I found that fascinating. That the work to which he was devoting his life didn’t change anything inside him. “And I find that fascinating,” I did tell him. “That you can know something but not have it affect how you feel it. For me, there isn’t such a distinction.” I pictured my time in the lab, learning about the infection. Flies fully possessed, fungus ready to murder.

“Yes,” I continued. “I know what I feel and I feel what I know.”

I left the Elya Lab the following month. My time in the laboratory was one of constant curiosity and exciting research. I knew I was leaving behind something meaningful. Still, my experience with the flies had shown me that I did not want to be a scientist. I wanted to be something different.

Three weeks ago, I changed my concentration to Philosophy. Perhaps time will show me that, much like science, philosophy is insufficient to find the face of truth. Until then, I am happy to keep on looking.

—Magazine writer Andrés Muedano can be reached at andres.muedanos@thecrimson.com.