News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

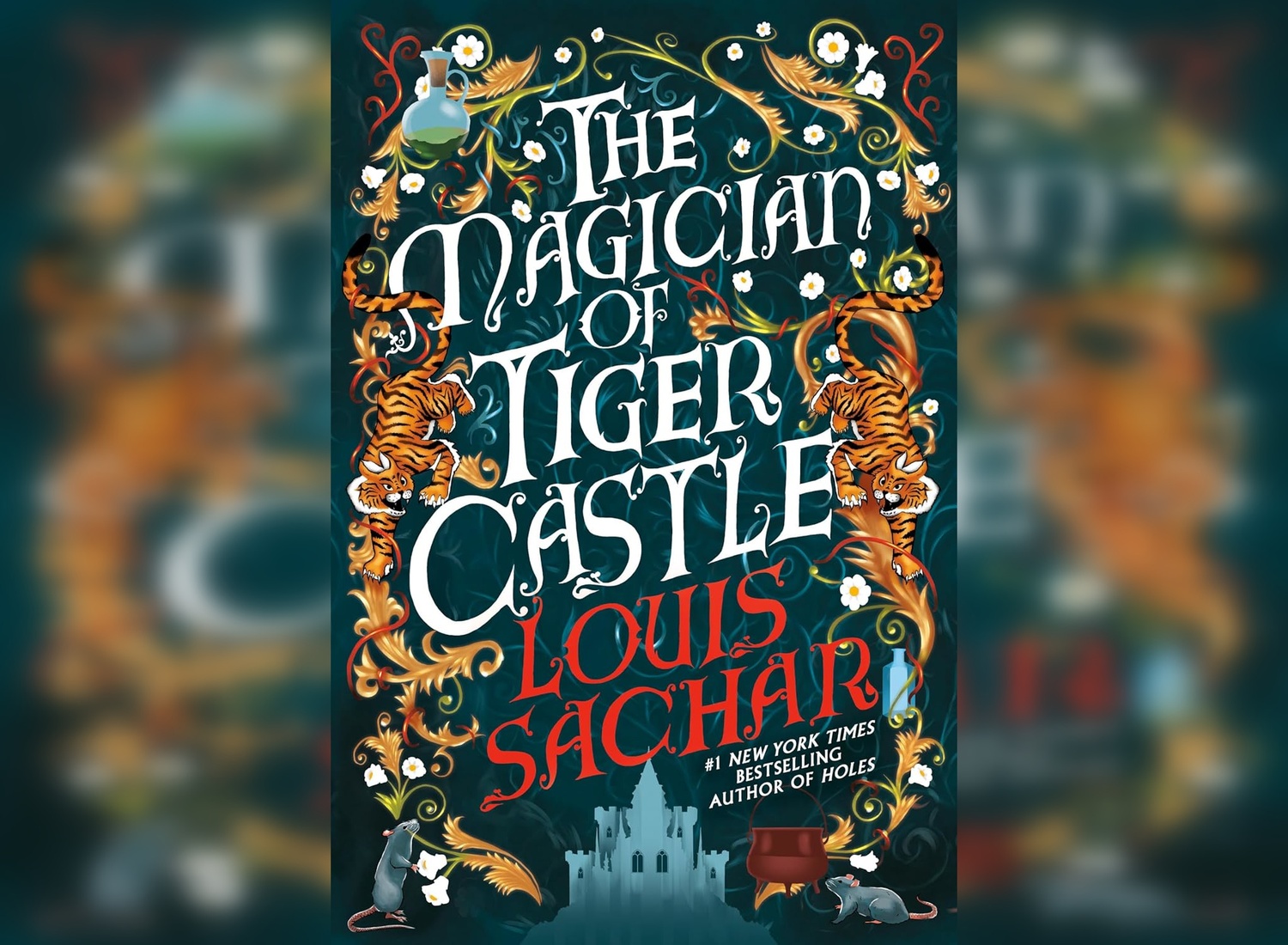

‘The Magician of Tiger Castle’ Review: Louis Sachar’s Absurdly Intuitive Fairytale for Adults

4 Stars

Could you really survive on preserved peaches alone in the desert? How can a building not have a 19th story but still have 30 stories in total? Louis Sachar, author of “Holes” and “Sideways Stories from Wayside School,” writes children’s stories where the absurd becomes intuitive. This matter-of-fact approach to the uncanny continues in Sachar’s first book for adults, “The Magician of Tiger Castle,” a delightful novel featuring a world that feels both familiar and unexpected.

Set in the fictional kingdom of Esquaveta, “The Magician of Tiger Castle” is told through a series of flashbacks experienced by court magician Anatole as he sits in a 21st-century cafe, recalling the lead-up to the “wedding of the century,” which is set to take place between Princess Tullia of Esquaveta and Prince Dalrympl of Oxatania. The princess’ relationship with Pito — a servant in the castle — is exposed and condemned, and Anatole is tasked with creating a potion to dull the princess’ will and force her to cooperate with the arranged marriage.

With an attention to detail and tactful worldbuilding, Sachar weaves a plot that a reader cannot help but see through to the end. Early on, we become immersed in Anatole’s perspective, nodding along as he considers dried blueberry skins (a rare American product). Sachar makes it make sense, and soon enough, you don’t even blink an eye when characters deter a bear attack with a wheel of cheese.

Although the story is set in an almost fairy tale world of princesses and magic, Sachar grounds the reader with his complex characters and overt commentary on historiography. Anatole, as he drinks a cappuccino in the 21st century, reflects on the past with humorous quips that question how history is written.

Sachar writes, “Just because scholars and historians have chosen to ignore it doesn’t diminish its importance. Rather, it reveals the biases and ignorance of these so-called experts!”

It’s made clear from the start that history and historians are not to be trusted. Even Anatole, whose personality shines through every line of narration, is an unreliable source. At several points throughout the story, Anatole admits that he is not telling us what happened word-for-word, but rather what he remembers and what would make most sense to English speakers. It makes the reader wonder: What else has been lost to time and translation? With this experimental structure, Sachar invites us to question what we are told, and consider the nuances of perspective.

Precisely because of his bias, Anatole begins to feel familiar to the reader very early on in the story. From his passion for tea to his chronic clumsiness, Anatole is a charming main character with a real set of flaws that set him apart from other protagonists. At many points in the story, he is ridden with fear and doubt even as he makes choices that should seem easy, like whether or not to help 17-year-old Pito escape his unjust beheading.

“I knew [helping Pito escape] was just a fantasy. For one thing, it would require courage and bold action on my part. It was just a way to take my mind off my own failures,” Anatole says.

It is in spite of these fears that Anatole grows, right before the reader’s eyes, and when this growth is brought into question, the reader does a double-take. The ending is bittersweet — emphasis on the bitter — bringing the tale to a screeching halt in a way that emulates Anatole’s experience. The reader is left hanging without any real closure, abruptly thrust forward hundreds of years without the anchor of characters that have become so familiar.

While disappointing, the ending is not senseless. It’s a reminder that sometimes things are never resolved, that growth is not linear and time keeps moving no matter how much things matter in the moment. It challenges the idea of a happy ending and invites the reader to accept it, the way Anatole did. It’s realistic and sad.

In truth, “The Magician of Tiger Castle” is not so different from Sachar’s other books. The only aspects of the novel that sets it apart from his children’s books are some references to mature themes like sex and the use of profanity. Neither of these, however, are central to the story. What is central is the immersive experience, the absurdity, and the careful braiding of structure and theme.

Sachar’s new novel seems to blur the line between storytelling forms designed for children and the more complex aspects of adult life. Anatole may be a magician tasked with turning sand into gold, but he’s also a middle-aged man haunted by regrets. “The Magician of Tiger Castle” is a fairytale that asks the question: When do I change for the better, even if it goes against who I’ve always been?

—Staff writer Micaela S. Arenas can be reached at micaela.arenas@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.