Nobel Laureate Martin Karplus ’51 Remembered as Attentive Mentor, ‘Pioneering’ Chemist

Martin Karplus ’51 developed ground-breaking computer models to study chemical reactions and molecular dynamics, mentored hundreds of scientists, and won a Nobel Prize in Chemistry. But his love for the sciences began with another discipline — biology.

Martin Karplus ’51 developed ground-breaking computer models to study chemical reactions and molecular dynamics, mentored hundreds of scientists, and won a Nobel Prize in Chemistry. But his love for the sciences began with another discipline — biology.

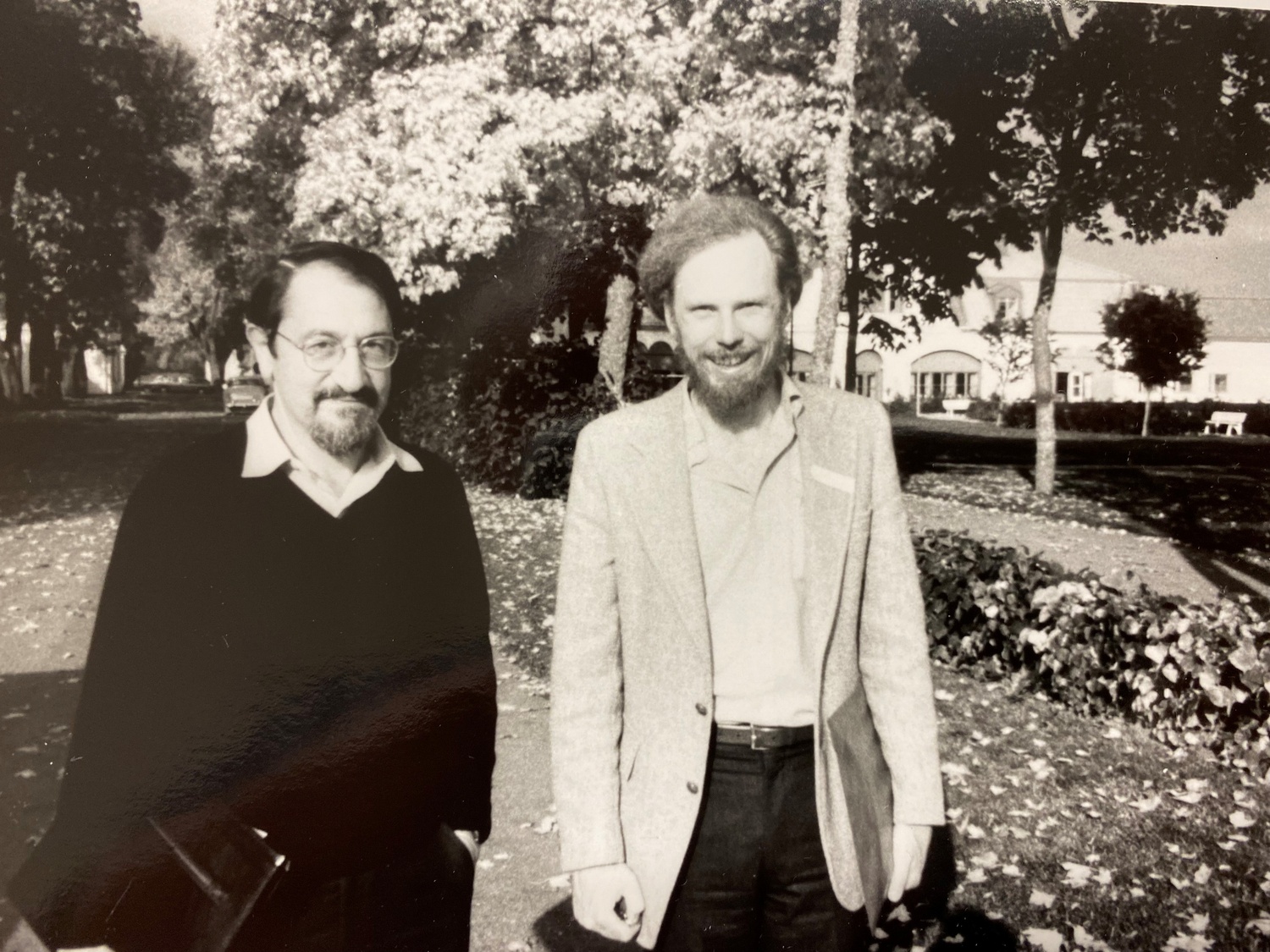

“That’s not something that just came out of the blue,” former colleague J. Andrew McCammon — a chemist at the University of California, San Diego — said. “As a young boy he got a microscope, and was thrilled with that.”

Karplus, who was a Chemistry professor at Harvard, died on Dec. 28, 2024, at his home in Cambridge, Mass. He was 94.

His friends, family, and students recalled him as a man of many talents and passions — from his research in chemistry and his love for biology to his thoughtful mentorship of hundreds of students.

“Science and society are so much better off because Martin Karplus lived,” wrote former colleague and friend Robert J. Petrella in a statement to The Crimson.

‘Intertwined with the 20th Century’

As a child, Karplus fled with his family from Austria to the United States to escape the Nazi regime — an experience which his family said shaped his career as a scientist.

“Martin’s journey as a refugee affected his view of the world and approach to science,” his family wrote in a statement. “To this experience he credited his willingness to venture beyond well understood research areas and ask questions.”

“His life is so intertwined with the 20th century history,” Karplus’ former Ph.D. student Benoît Roux said.

After receiving his undergraduate degree in Chemistry and Physics at Harvard, Karplus was torn between studying biology at the California Institute of Technology or chemistry at the University of California at Berkeley. He resolved this dilemma after receiving advice from another legendary scientist — J. Robert Oppenheimer.

McCammon said that Karplus’ older brother “steered Martin to Robert Oppenheimer,” who described CalTech to Karplus as a “shining light in a sea of darkness.” Oppenheimer’s comment led him to attend CalTech, where he received his Ph.D. in 1953. Karplus then completed his postdoctoral studies at Oxford, returning in 1966 to work as a professor of chemistry at Harvard.

Roux — who currently works as a professor at the University of Chicago — said Karplus focused on areas where he could make an impact with his research.

“He said it’s important to work on something where you can do something,” Roux said.

Karplus did just that.

Beyond his Nobel Prize-winning work as a chemist, Karplus developed a groundbreaking software program and published more than 800 papers that influenced an array of different scientific fields.

“He spearheaded the establishment of an entire field — the simulation of biomolecules,” Petrella wrote. “The Nobel is a great honor, of course — but in Martin’s case, it actually undersells his accomplishments.”

But Karplus wished he won the Nobel Prize for another aspect of his work instead: molecular dynamics.

“In sharing a Nobel Prize for Chemistry, Martin was unhappy that it wasn’t given for the molecular dynamics work, which he thought was really the work that was most influential that he was involved in,” McCammon said.

“He was really most proud of the molecular dynamics work, and felt that that really provided the most insights, but also the most practical ramifications from the use of theoretical chemistry and biology,” he added.

Marci Karplus, Martin’s wife, said her husband “was very intense about and committed about anything he did.”

Petrella wrote that Karplus’ strong-willed nature was a key component of his scientific success.

“Martin’s insistence on quality and accuracy over speed sometimes annoyed people, but it’s one of the reasons why he was able to build stable, reliable frameworks for research, most notably the CHARMM program,” he wrote.

CHARMM — Chemistry at HARvard Molecular Mechanics — is a software program created by Karplus and his research team which models interactions between biological molecules. Axel T. Brunger — a Stanford molecular and cellular biology professor who studied under Karplus as a postdoctoral student — said CHARMM was a “lasting contribution” in its own right.

“Martin went beyond just pioneering computational chemistry, he provided a very powerful tool — the CHARMM program,” Brunger said. “He made major scientific contributions, but he also created tools to make these accessible.”

‘A Perfect Advisor’

Beyond his scientific accomplishments, Karplus’ former students remembered him as a patient mentor and skilled instructor.

“In three lines, he would make me understand the whole seminar,” Roux said. “He was always making it look simple.”

Karplus’ former student Alex MacKerell — who is now a pharmaceutical sciences professor at the University of Maryland — said Karplus’ great intuition and knowledge of biochemical and chemical systems would help his students' projects move forward.

“Martin was a very serious individual who could focus on a specific problem and comprehensively address that problem and come up with novel insights and solutions concerning that problem,” said MacKerell.

Beyond his own research, Karplus mentored more than 200 graduate students and postdoctoral fellows across his career. Many have since gone on to their own successful scientific careers.

“They all remember him as somebody who was thoughtful, and they recognized that he was incredible in terms of science and his insights,” Marci Karplus said. “He continued to follow them scientifically when they would leave the group. And we also continued to follow them personally.”

“On a personal level, what Martin did for me over my scientific career could probably fill a book,” Petrella wrote.

His former students said they were struck by the trust Karplus placed in them to conduct their own research.

“He cherished and encouraged young scientists to become independent themselves,” said Harvard researcher Victor Ovchinnikov, who worked for years in Karplus’ lab.

As a student in Karplus’ lab, Roux remembers, he was allowed to lead a project involving ion channels — a subject which he was familiar with from his time earning a master’s degree in biophysics.

“My work on the ion channel was really my own — and he always treated it like that,” Roux said. “He never expressed any ownership of the general framework of the product.”

Brunger shared a similar experience, and said that Karplus would let his students work on “whatever sounded interesting, wherever the path would take us.”

Brunger added that Karplus meticulously followed all of his students’ research, which he said was “quite remarkable” considering the “fairly large group” of researchers.

“He manually wrote the corrections in the manuscript, and he made very detailed comments,” he said.

Even when Karplus was vacationing in the French Alps, Brunger said, he was swift with feedback. Brunger recalled receiving detailed comments on manuscripts he faxed to Karplus from halfway across the world.

His former students also remembered that Karplus supported them beyond his lab and into their professional careers.

After Roux won the Kenneth S. Cole Award from the Biophysical Society in 2023, he sent Karplus an email thanking his former mentor for his guidance.

“I believe I will forever carry what you transmitted to me and honor your teaching,” he wrote. “How lucky was I to find the perfect adviser at that time in my life.”

Karplus quickly responded to his former student, congratulating him on his accomplishment and thanking him for his work in the lab.

“Thank you for reminding me of the time we worked together and learned from each other,” Karplus wrote.

“I was very touched that he wrote back saying that he remembered when we worked together — not ‘when I was a student,’ but ‘when we worked together,’” Roux said.

‘The Linchpin’

Though Karplus leaves behind a legacy of groundbreaking research, his former students said he did not let science consume his own zest for life or his respect for others’ pursuits.

“He understood that people can be interested in something else in life too,” Roux said. “ You never had the impression that he was devoured whole by just science.”

“Martin had, I think, a very uncanny appreciation of not just science but also art and politics,” Ovchinnikov said.

McCammon, who studied chemical physics under Karplus at Harvard in the 1970s, recalled sitting in on music and art courses during his time at the University.

“Martin would kind of grump a little bit that I was taking so much time away from science, but he wouldn’t grump too much, because he would do the same thing,” McCammon said.

Karplus — who was known for his love of food and wine — combined his passion for art and science in cooking.

“He spent short periods working in different restaurants, basically just going there for a few days just to get the experience of working there,” MacKerell said.

At heart, McCammon said, Karplus was a connoisseur.

“Anything he did, he liked to do it at a high level,” McCammon said. “That was reflected in virtually everything he did in his life — photography, the science, the cuisine — he always had very high standards and appreciated good things.”

Marci Karplus said her husband was “the linchpin” of their family.

“He had tremendous energy and tremendous drive, and it could be a lot to keep up with, but it was also really rewarding,” she said.

—Staff writer David D. Dickson can be reached at david.dickson@thecrimson.com.

—Staff writer Ella F. Niederhelman can be reached at ella.niederhelman@thecrimson.com.

Correction: January 10, 2024

Due to an editing error, a previous version of this article incorrectly stated that J. Andrew McCammon teaches at the University of San Diego. In fact, McCammon is a professor at the University of California, San Diego.