News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

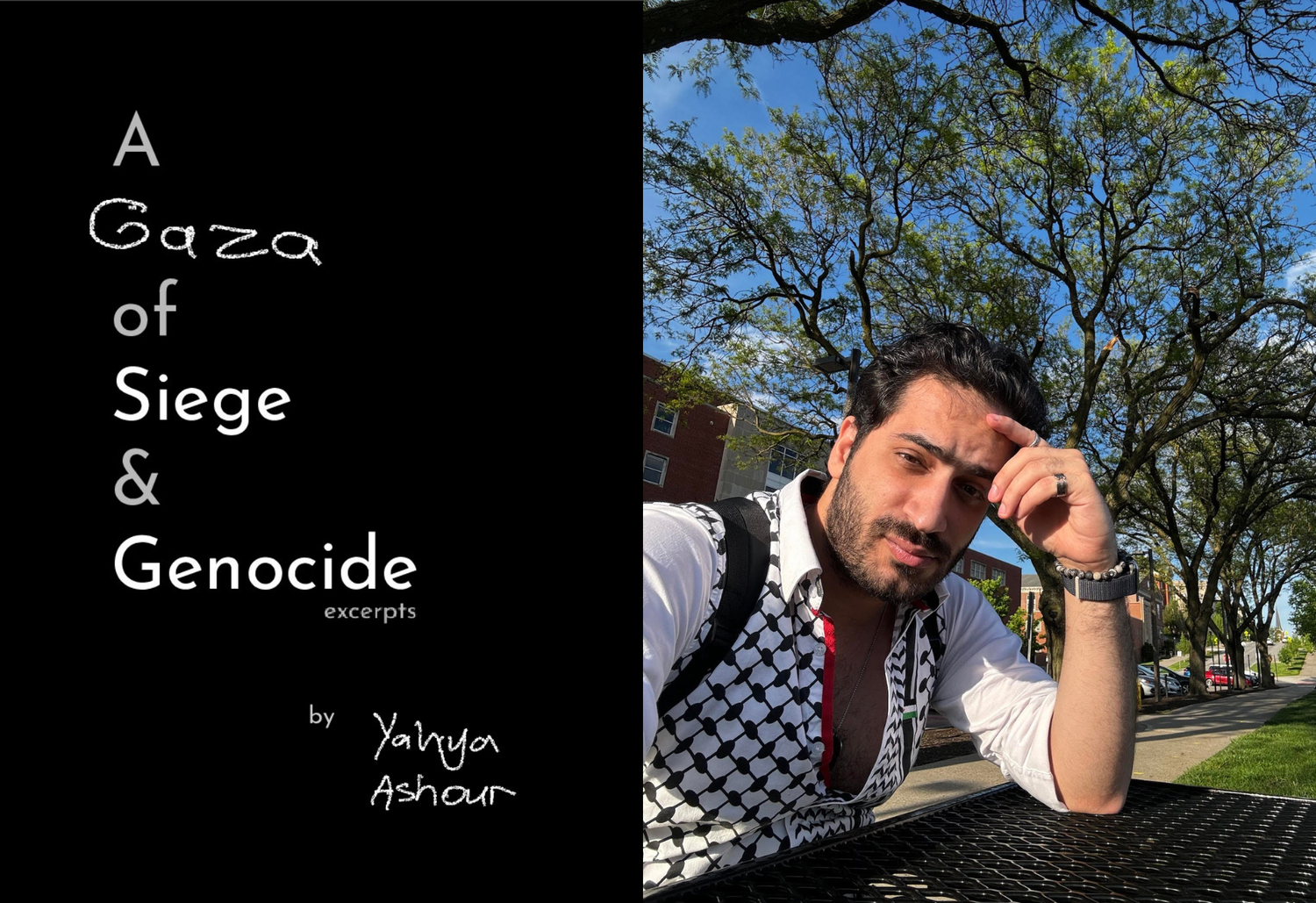

Artist Profile: Yahya Ashour on the Struggle to Represent Loss

Updated August 26, 2024, at 10:40 p.m.

“How do you write the genocide in poetry?” Gazan poet and author Yahya Ashour asked in an interview with The Crimson.

Ashour is an honorary fellow at the University of Iowa and a children’s book author who has read his poetry at over 50 U.S. organizations and universities such as Stanford and Princeton. Unable to return home to Gaza since October, Ashour shared how the horrors of the ongoing humanitarian crisis placed pressure on the poet and the form of his poetry.

Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel sparked the current war in the Middle East, which has lasted for more than 10 months. Israel’s invasion of Gaza has killed more than 40,000 people in Gaza, where the Hamas-run Health Ministry does not distinguish between civilians and combatants.

The majority of the dead are women and children, according to the Gaza Health Ministry.

“It’s not just one bullet in one head. It’s massacres over massacres over massacres,” Ashour said. “And it’s not just one type of massacre. It’s different types and all kinds of massacres and all kinds of crimes that I couldn’t even think of. Every day it gets worse.”

In response to these complexities, he said that his poems have become more “suffocating” and “layered” in an attempt to encapsulate the sheer magnitude of these losses.

For Ashour, writing poetry is a difficult process. He describes the moment a poem surges into him like a “volcano” — it is forceful and uncontrollable. More than that, it is unpredictable.

“I don’t think a lot about inspiration,” Ashour said. “I think poetry always comes in the most inconvenient moments, and there are a lot of them right now in my life.”

He balances the intensity of his poems’ initial creation with his lengthy editing process, which requires Ashour to gain a feeling of “estrangement” from the poem. He finds that the time he takes to forget the poem is necessary to better judge its quality.

However, Ashour finds difficulty in taking the time to edit and re-edit, as he must navigate both his personal losses and the struggle for representation. At the start of the war, his house was destroyed and his family placed in danger.

Even then, he chose to focus on raising awareness through his art.

“It’s not the time to think about myself,” he said. “In the beginning, I received a lot of messages from my friends saying that you’re in the U.S. You have to let these people know.”

As a result, Ashour reached out to university professors and shared his writing across the U.S. through poetry readings. He sees poetry as a platform to connect people emotionally and mentally with the war in Gaza.

“I think it is important that people get to see what Arabic sounds like,” he said, explaining why he starts all his readings with a few poems in Arabic.

These moments of reading in Arabic provide him with a brief respite from the pressure he faces when reading aloud. He joked that even if he messes up, not many people will figure it out. The anecdote was brief but telling: The work of a poet, especially for one who has to speak about a devastating war and humanitarian crisis, is taxing.

Even though the process can be painful and exhausting, Ashour is a staunch believer in the power of poetry. He spoke fondly about the empathy and connections he found in audiences’ reactions to his work. He also released a poetry e-book, “A Gaza of Siege and Genocide,” with all its proceeds directly funding his family’s escape to Egypt.

“To my family: This is me trying to save you with my words, hoping one day my words too will reunite us again,” he said, reading aloud from the e-book.

Ashour remains steadfast in the face of immense difficulty. To him, silence is shameful and dehumanizing.

—Staff writer Sean Wang Zi-Ming can be reached at sean.wangzi-ming@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.