In Allston’s Brazilian Community, New Arrivals Suffer in Overcrowded Apartments

Dozens of people, including 10 Brazilian immigrants who live or lived in overcrowded apartments in Allston-Brighton, described dangerous physical conditions and an overwhelming mental toll that came with their housing situation. They see few other options.

In Allston’s Brazilian Community, New Arrivals Suffer in Overcrowded Apartments

Dozens of people, including 10 Brazilian immigrants who live or lived in overcrowded apartments in Allston-Brighton, described dangerous physical conditions and an overwhelming mental toll that came with their housing situation. They see few other options.BOSTON — When Zilda, her brother, and her two children first arrived in the United States from Brazil in 2021, they had to share everything.

They shared a three-bedroom apartment in Brighton with five other people, some of whom slept in the living room. The nine subtenants together shared a kitchen and a single bathroom. Inside their one bedroom, Zilda and her family all shared a single bed.

And everyone in the unit shared the stress of trying to avoid discovery by a landlord unaware that her unit was secretly being sublet.

The stress was for good reason. The landlord’s nephew, who lived upstairs, eventually realized too many people were going out of the same unit to work each day and reported them to his aunt. All of the subletters were turned out.

Allston-Brighton, where rentals comprise 90 percent of the housing stock, has long been associated with overcrowded and poorly maintained units. Many locals know the neighborhood for hosting a large portion of the city’s student population, where five or six students may pack into the same unit.

City officials cracked down on student overcrowding after a Boston University student living in an illegal apartment died in a 2013 house fire because the unit lacked a second exit, prohibiting five or more unrelated persons from sharing an apartment.

But even as the city has tried to quash overcrowding among young renters in the neighborhood, Allston’s sizable population of immigrants arriving from Brazil and Central America has lived for years under similarly cramped and dangerous conditions to far less attention. The problem has gotten worse in recent years as economic instability in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic channeled an influx of immigrants into an increasingly unaffordable housing market.

They live, as many as 13 to a single apartment, in informal sublets with rental agreements sometimes scribbled onto a piece of paper. As subtenants, they are at the mercy of a subletter who may put extreme limits on their ability to move around the apartment, use common spaces, or even turn on the heat in the winter.

Over the last several months, The Crimson spoke with dozens of people in and around Allston-Brighton about the problem of overcrowding within the area’s long-standing Brazilian community. Local clergy, housing activists, and nonprofit workers told a story of a decades-long problem that has grown worse since the pandemic as family arrivals have spiked and the city’s housing crisis has reached new heights.

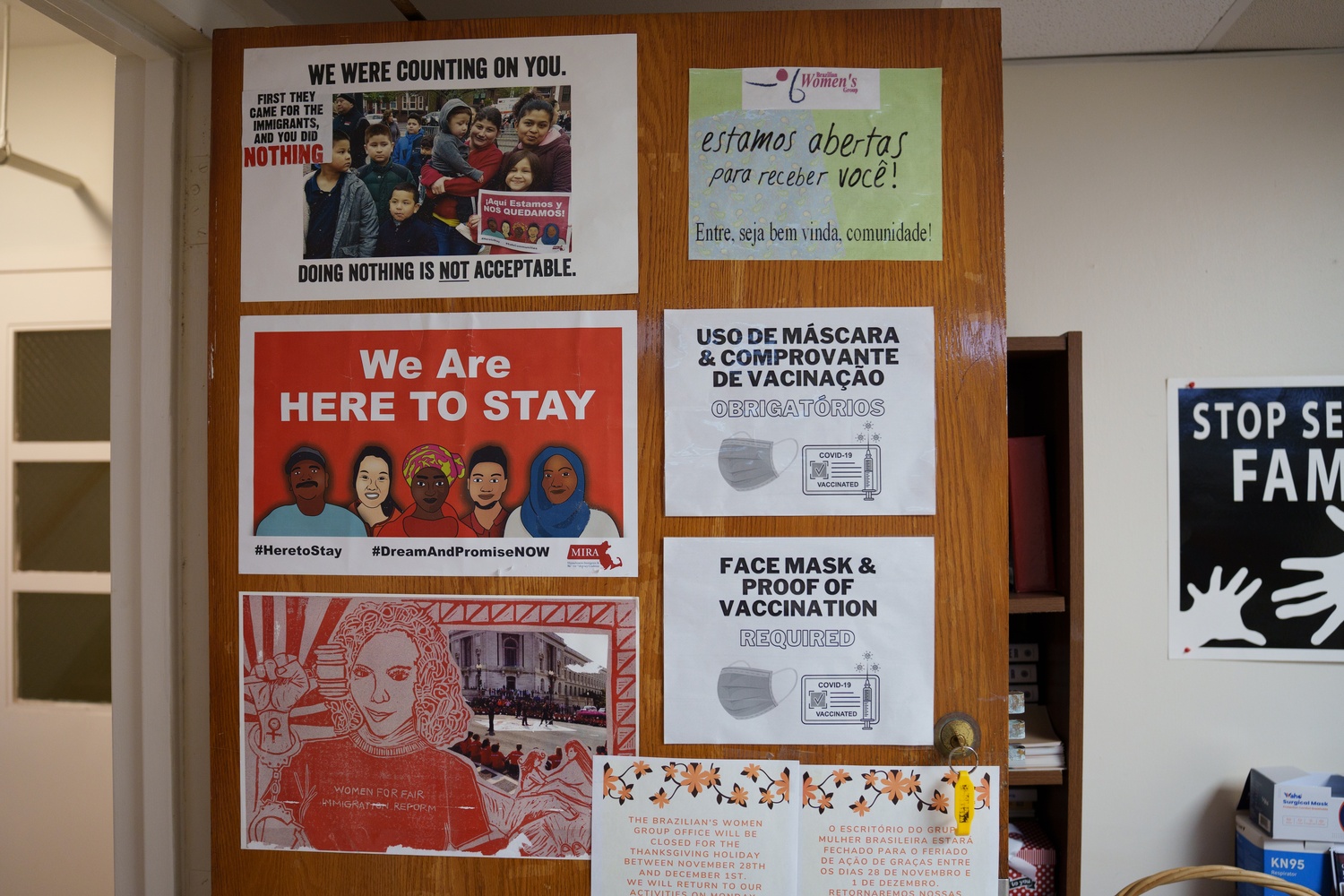

“Eighty percent, maybe more, of the calls we get from people, the whole family lives in a room,” said Heloisa M. Galvão, the executive director of the Brazilian Women’s Group, a Brighton nonprofit. “Sometimes they even rent the living room, a corner in the kitchen.”

The Crimson interviewed 10 different people, almost all in Portuguese, who live or have lived in overcrowded apartments, some of whom spoke on condition that they would be identified by their first name, fearing retribution from landlords. The residents described dangerous physical conditions in overcrowded units and said sharing such a small space with so many other people took an overwhelming mental toll.

“We used to see rats wandering at night. I was afraid of my baby being born under these conditions, living there,” Zilda said. “Life is really hard, because no one enjoys living this way.”

“We feel like nothing, like nothing,” she added.

‘Abandoned Inside of a Room’

When Geilson, a Brazilian painter who asked to be identified by his first name, arrived in Watertown — just across the river from Allston — in 2021, he landed in a single bedroom for $1,200 a month, far less than what he would have paid for a full apartment in Boston.

But there were strings attached.

He was prohibited from using almost anything outside the bedroom. He had access to the kitchen only once a week and had to keep a separate fridge in his room with his own food. Even in the bitter New England winter, he was forbidden from turning on the heat.

For Geilson, like so many other Brazilians who arrive in Boston without adequate connections or resources, such restrictive and unstable living situations are frequently the only way to get by.

Boston’s eye-popping rents — combined with debt reaching $20,000 from the journey north — make it sometimes impossible for many recent Brazilian immigrants to afford a traditional apartment. Even if they could, many Brazilian residents often lack the necessary documents, like identification or proof of income, required to enter a formal rental agreement. The fact that many are living in the U.S. without legal immigration status adds a further layer of risk and complication.

So, they wind up renting a room — or portion of a room — often from another immigrant of the same background, cheaply and off the books. And they make do.

Geilson’s subletter “spent the whole winter without turning on the heater,” Geilson said in Portuguese. He ultimately settled for using a space heater given to him by a sympathetic coworker — but only after the subletter had fallen asleep each night.

“I only had access to the kitchen once a week,” he said. “I had to cook for the whole week.” And the living room was off limits entirely.

“It was very hard,” he said.

The situation is even harder for children. Parents said their children struggled to understand the restrictions associated with a communal apartment, and expressed concerns that living in such a confined environment would hamper a critical period of development. Many parents said children can develop behavioral issues under such conditions.

“They are trapped inside the bedroom,” said Mirliane Mendes, a house cleaner and babysitter who lives with two children in Brighton, speaking in Portuguese. “It affects socializing with other people — it’s inevitable.”

Many parents said they tried to keep their children strictly confined to the bedroom — both to avoid bothering the other tenants and to keep their children safe.

Childcare also presents a constant dilemma. Parents are caught between bringing their children with them to work or leaving them in a house with people they hardly know, where kids are sometimes left under the supervision of young children who happen to be just a few years older.

Living in such close quarters with strangers also puts children at high risk for sexual abuse, Galvao said.

Alessandra Fisher, the director of immigrant integration and elder services at the Massachusetts Alliance of Portuguese Speakers, wrote in an emailed statement that “children growing up in these conditions are frequently left traumatized.”

“Our staff educates clients about the potential risks of sharing apartments, but unfortunately, many times families feel they have no other options,” she added.

Zilda, now living in a three-bedroom apartment and working as a house cleaner, said that living in those conditions with her children, then 15 and 17, left her with a deep sense of failure.

“The worst part is seeing your children,” Zilda said. “We want to give our children the minimum comfort. A nice place to sleep, a comfortable home for them to come back to.”

For Mendes, living in an overcrowded apartment was an incredibly isolating experience.

“You feel abandoned inside of a room,” she said. “Nobody speaks to anyone.”

“You don’t have a friend,” Mendes added.

‘No Questions Asked’

As serious as the mental and physical toll can be, immigrant families in overcrowded apartments also described living in fear that they might be thrown out onto the street at any moment.

Because most overcrowding happens informally and without the landlord’s knowledge — frequently in violation of rental agreements or local ordinances — current and former residents described having to be especially discreet about their living arrangements. If the landlord finds out, the result can be eviction.

Safi Chalfin-Smith, who works in local outreach and emergency housing assistance for the Brazilian Worker Center, said the organization frequently encounters homeless families who were forced out after they were discovered living with a relative or friend.

“Doubling up really puts people at risk of eviction,” she said.

When Zilda was evicted from her overcrowded Brighton apartment, she was panicked.

“I was scared because it was just me and my children. How was I supposed to find a house?” Zilda said. “But then my daughter began working, and helped me rent a one-bedroom apartment for us.”

The illicit subleasing can also create a dangerous incentive for both parties to keep quiet when things go wrong inside the apartment — a common occurrence, considering that many overcrowded apartments are decades old and frequently have bed bugs, mold, leaks, or malfunctioning utilities.

The tenant subletting their apartment may decide to take on the effort or expense of small repairs in the apartment to avoid calling the landlord and risking discovery of the subtenants. More severe problems like pest infestations — which are harder to address without the landlord’s help or knowledge — may simply go unaddressed.

Geilson, who is himself now subletting a room to a family for $1,200 a month, said he takes pains to keep up the apartment, like repainting the walls or repairing issues in the bathroom.

“You don’t share any of these needs with the landlord to prevent him from going there as much as possible,” he said. “This way there are no questions asked.”

‘A City With Corners’

Though overcrowding has risen substantially in recent years, most people interviewed for this article stressed that it has been a problem in the area for decades.

“This is as old as Brazilian immigration is to Boston,” said Carlos Siqueira, a professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts Boston and coordinator of the Gaston Institute’s Transnational Brazilian Project.

Brazilians began moving to Allston in the 1980s, as Brazil’s economic crisis spurred a wave of immigration to the U.S. Coastal Massachusetts, with existing communities of Portuguese speakers, immediately emerged as an attractive destination.

Just as today, financial and institutional barriers to renting drove many arrivals to the neighborhood to overcrowd while they found their footing — although most at that time were single adults, not families.

Roselia Sousa, a house cleaner who first came to Allston in 1986, said she shared an apartment with seven other women. They all slept on mattresses on the floor.

“We lived in a one-bedroom apartment and no one had a bed,” she said.

The Brazilian population throughout Eastern Massachusetts has continued to grow from just a few thousand in 1980 to more than 100,000 in 2017, according to figures from the U.S. Census Bureau. That figure almost certainly omits scores of immigrants living in the state without legal immigration status.

Overcrowding worsened as the steady flow of new arrivals coincided with Boston’s growing housing shortage. Local nonprofit workers said things only escalated following the pandemic: In 2021, U.S. Customs and Border Protection recorded almost 20 times as many apprehensions of Brazilians as just five years ago, in 2016.

As Brazilian immigrants came in growing numbers to Massachusetts, many found a landing pad in Allston-Brighton, which by then already housed a vibrant Portuguese-speaking community.

“It’s almost like temporary housing until they find other ways to survive in other neighborhoods,” Siqueira said.

The neighborhood is walkable and serviced by the Green Line, commuter rail, and many buses. The local Catholic church, Saint Anthony Parish, offers weekly masses in Portuguese. Several nonprofits cater specifically to Brazilians, while Brazilian restaurants, butcheries, and bakeries offer traditional meals — cooked with ingredients imported directly from home.

“It looks like where they come from,” said Galvão, who leads the Brazilian Women’s Center. “We have an expression that says, ‘A city with corners,’ meaning you walk on the street and you find the people you know. You meet people you know and you stop and chat.”

“Allston-Brighton has that feeling for us,” she said.

Fear of Speaking Out

Advocates looking to improve substandard housing conditions for overcrowded families said they were stuck between a rock and a hard place: ask for help from the city and spark fears of eviction, or say nothing and let people continue living in cramped and dangerous conditions.

Even if Boston’s Inspectional Services Department — who stressed that they would never turn any occupant out onto the street — becomes aware of overcrowding, the housing resources they ultimately connect residents to are stretched dangerously thin.

And though the ISD can enforce violations of the state sanitary code, which requires 150 square feet of space for the first tenant and 100 more square feet for each additional tenant in rental units, issuing a citation to the landlord only risks forcing residents from what may be their only option for housing.

Galvão said many immigrants don’t speak up out of fears of retaliation from their landlords or getting in trouble with the city. But she encouraged residents to reach out to ISD, adding that anyone paying rent to live in an apartment, formally or not, has “all the rights of a tenant.”

“The major problem that I see is fear,” she said. “When you are fearful, you don’t raise your voice, you don’t raise your hand, you don’t look ahead — you try to make yourself invisible.”

“They have the right to a clean apartment, that everything works,” Galvão added. “They have to have an apartment clean of bed bugs, of cockroaches.”

In an interview, Boston ISD’s Assistant Director of Housing Inspections Regina Hanson said that the department was meant to serve occupants threatened by unsafe conditions — not be a threat itself. She said the department does not evict occupants, does not ask about immigration status, and requires an occupant’s informed consent before even entering.

“When we go in to do the inspection, we’re looking at the violations of state sanitary code. We are not looking at people’s immigration status,” Hanson said. “Occupants are occupants.”

She added that the department would connect any displaced occupant to “wrap-around” services from the city’s housing and immigration departments.

But the city’s main ways of offering housing assistance to residents — lotteried affordable units, public housing, or Section 8 vouchers — often come with yearslong wait lists. ISD itself has limited staff, making it difficult to carry out its mandated inspections of each apartment in the city every five years. Some landlords never register their rentals with the city to begin with, meaning they are never subject to a regular inspection.

In a statement, ISD Commissioner Tania del Rio said that the department inspected 25,000 apartments a year, and has recently been increasing the number of proactive inspections that it performs.

While Allston-Brighton sees a particularly high concentration of overcrowding, the issue persists across many areas of the city and many different demographics, including Irish and Chinese immigrants and students.

Zafiro Patiño, an organizer with the housing justice group City Life/Vida Urbana, said she has seen overcrowded conditions all across Boston.

“There are mattresses on the floor, forget about rooms,” she said. “You feel like, ‘Wow, this is happening? This is Boston?’”

—Caio Alvim, Livia Calixto, Mariana Rae, Maria Rodrigues, and Rita Palacio contributed translation work.

.—Staff writer Jack R. Trapanick can be reached at jack.trapanick@thecrimson.com. Follow him on X @jackrtrapanick.