News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

We’re Harvard Library Workers. We Stand in Solidarity with the Study-Ins.

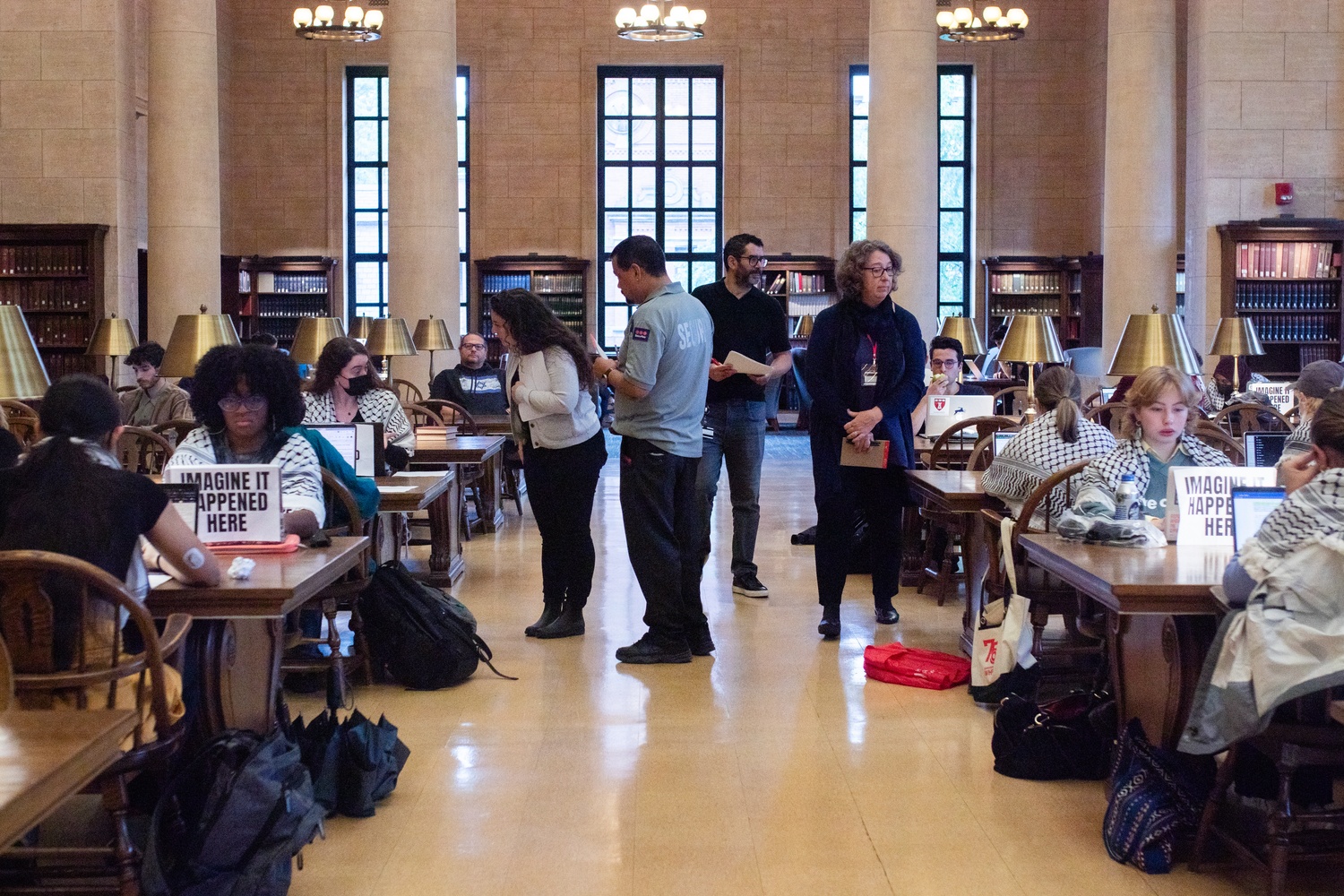

On Oct. 2, Harvard library workers — including the two of us — received an email from University Librarian Martha J. Whitehead informing us of a “demonstration” that took place in Widener Library two weeks prior. The email did not note the nature of the action (sitting and reading silently with signs) or the punishment (a temporary library ban). We were told, though, that the demonstration “undermines our commitment to provide an inclusive space to all users.”

We fail to see how studying silently amounts to a disruption, and we reject the bans issued in response. We write to let study-in participants know that there are library workers who stand in solidarity with them. We are not alone: Many of our colleagues support these sit-ins but did not join us in authoring this piece out of fear of repercussion.

The Harvard library system runs on the labor of library workers like us, many of whom believe a genocide is taking place in Gaza, call on Harvard to divest from that genocide, and applaud the study-ins. The decision to bar patrons from the library was made by central library administration, who then compelled local library leaders, security workers, and library staff to follow their mandate, often against their own moral compasses.

Libraries have a long history of espousing neutrality. One-time Harvard librarian Charles A. Cutter ’55 told the American Library Association in 1889 that the librarian is “of no party in politics.” Today, the ALA Code of Ethics guides librarians to “distinguish between our personal convictions and professional duties.”

But these appeals to neutrality are themselves political. Libraries are not neutral — no institution or body of people can ever truly be. In fact, claiming neutrality creates a chilling effect and facilitates the suppression of dissenting voices by mainstream ones. The “inclusive space” envisioned for Harvard libraries and their reading rooms is not really inclusive — it is the traditional, “neutral” space.

In Harvard’s vision, a shared conviction made publicly known in any way — even silently — is a breach. Community members bearing similar, visible messages are an imposition. They break the dutiful, professional atmosphere that librarians have worked hard to construct. They are not silent enough.

But ultimately, the silence sought in any “neutral” space is not a silence meant for everyone. Where this politicized version of silence exists — in our libraries, around campus, and across the country — the violent actions of settler-colonial states and our institutional ties to them go unchallenged.

The email we received characterized study-in participants as purposely making their presence known. It is at least true that the participants bore a message. Their message caught the attention of those in power and of those accustomed to the silence that power manufactures. Only those invested in maintaining that silence could find pieces of paper taped to laptops advocating for Palestinian rights disruptive.

It is impossible to see the recent library bans as disconnected from the content of the participants’ messaging. For the past year, ever since this wave of ethnic cleansing in Gaza began, we have received frantic, University-wide emails about campus antisemitism straight from the Harvard administration. Over the course of the same year, we received far less official messaging about the safety of Palestinian and pro-Palestine students.

The decision to ban students, faculty, and even library staff from Harvard libraries appears to be another chapter in the story of the past year, in which every moment of institutional silence is an enforcement of the status quo. It is fitting that community members advocating for Palestinian rights should gather in the library, a place of hushed solitude, to stand in solidarity against this silence.

As library workers, we take great pride in helping shape libraries into centers of exploration, discovery, and community. We take pride, for instance, in the libraries across the nation resisting right-wing movements to ban books.

As Whitehead herself acknowledged in a statement following her decision to ban faculty from Widener for their own silent study-in, a Baltimore public library stayed open as a sanctuary during the protests following the police murder of Freddie Gray. The parallel she draws, however, between 2015 Baltimore (where a library remained open to all during a period of domestic unrest) and campus today (where the library closed its doors to some during a period of global unrest) is baffling.

With these bans, Harvard libraries missed a vital opportunity to put their ostensible foundational commitment to “Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, Belonging, and Antiracism” into practice. By barring dissenting students, faculty, and staff for merely exercising their freedom of speech, we fear that Harvard libraries have indelibly damaged our relationship with library users and proved our stated EDIBA values to be hollow.

Library workers are guided by a mission of service; we serve library users by providing information that is essential to research and academic excellence. When we lose our community’s trust and undermine the library as a safe, antiracist, and truly inclusive space, we jeopardize our vital work and brand the library as an explicitly hostile and unsafe place.

Moving forward, Harvard libraries have the opportunity to fully embody their values and mission, repair their relationship with community members, and forge a path that is unequivocally aligned with the EDIBA values we claim to espouse.

We cannot pass up this opportunity. In the meantime, we library workers call on Harvard libraries to lift the library bans on students, faculty, and staff. And in the future, we implore Harvard libraries to refrain from disciplining those who study together, united not in disruption but by a shared conviction.

Maya H. Bergamasco is Faculty Research & Scholarly Support Librarian at Harvard Law School Library. Jonathan S. Tuttle is a cataloger of published materials at the Schlesinger Library.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.