News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

The 10 Best Harvard-Yale Games Over 149 Years

The iconic “Game” has been played for well over a century. Inevitably, some iterations of this Ivy League clash of the titans are better entertainment than others, begging the question: Which is the most unforgettable Game?

Lucky for you, dear reader, I have combed over newspapers, stat-sheets, and highlight reels aplenty to determine once and for all which contest was objectively the most legendary of all the Crimson-Bulldog face-offs on the gridiron. There are a few factors that sum together to build a legendary game. Incredible athletic displays, loaded stat sheets, and high-pressure highlights in the clutch all contribute to a thrilling game. But when that final whistle blows, the fans will know in their hearts whether or not they have all just witnessed a legendary game. Here is the definitive Hall of Fame, for The Game.

#10: Fitzmagic and the Undefeated Crimson, 2004 (Harvard 35, Yale 3)

If you have ever been unlucky enough to leave the Malkin Athletic Center as a Harvard tour group comes by, chances are that you have heard the story of the infamous prank some sneaky Yalies played on Crimson fans in 2004. The legend goes that disguised Elis tricked a large section of Harvard students to hold up placards spelling out a self-deprecating message. Yale’s biggest success in executing this practical joke is that its milking of the story is persistent enough to distract the world from the fact that Harvard bulldozed the Bulldogs that year. Led by captain, soon-to-be Ivy League player of the year, and eventual NFL quarterback Ryan Fitzpatrick ’05 — sometimes called “Fitzmagic” — the Crimson wrecking crew of ’04 also featured 15 All-Ivy selections, including Clifton Dawson ’07. If there is a rushing-related record at Harvard, chances are Dawson holds it. Season rushing touchdowns, career rushing touchdowns, single season and career rushing yards — all Dawson’s. Needless to say, the team the Bulldogs faced off against in the 121st Game was no joke. Big-yardage rushing plays from Dawson, Fitzmagic slinging dimes, and a 100-yard pick-six from Ricky Williamson ’05, clinching an undefeated season for the Crimson and an outright Ivy League title, all add allure to this iconic edition of The Game.

#9: College GameDay, 2014 (Harvard 31, Yale 24)

Despite Harvard-Yale being such a storied rivalry, its enjoyment tends to be (shamefully) contained to the Ivy League bubble. In 2014, however, college football legend Lee Corso and ESPN’s College GameDay program took on covering The Game for its 131st edition. With Harvard hosting, analyst Corso was tasked with predicting the outcome of the classic match-up, opting to sport the Bulldog headgear. What seemed to be the Crimson’s game the whole time, up a tally of 24-7 heading into the fourth quarter, almost turned into a disaster. With 3:44 on the clock, Harvard found itself all tied up with Yale. Luckily for Crimson fans — and unluckily for both Yale and Corso — Harvard had one more trick up its sleeve. Fighting the clock and a steady Bulldog defense, quarterback Conner Hempel ’15 worked his team from its own 22-yard line to Yale’s 35. In the final minute of play, Hempel unloaded a 35-yard dart to star receiver Andrew Fischer ’16, who cooked his defender with a double-move slant and go. Ball in arms and feet in paydirt, Harvard Stadium erupted. As soon as The Game was over, it was already being talked about as one of the greatest Games of all time.

#8: Gritty Game, 1894 (Harvard 4, Yale 12)

The 1894 match-up between the Crimson and the Bulldogs is perhaps one of the most brutal engagements between these two rivals in history. In an era where football was coming under fierce criticism for its elements of violence and aggression, the 17th playing of The Game only worsened the public perception of the sport. With no protective equipment, none of the spine-centric physical training, and absolutely zero research into concussions, 19th century football was a gritty game. And with the stakes being Ivy elitism, the scene was set for an extremely physical battle. In this merciless clash between the Ivy League titans, later dubbed the “Bloodbath in Hampden Park,” no punches were pulled — indeed, punches were thrown. Increasingly reckless tackles from both sides escalated into some completely illegal football plays. At a certain point, all hell broke loose and football was no longer the focus. The list of injuries stemming from dirty tackles and on-field fighting included a broken leg, shattered collarbone, poked eyes, broken and bloody noses, many head injuries, and a comatose player. Violence ensued on the streets as fans continued the fight even after the final whistle had been blown. The brawls were not without consequence. Following mass hysteria from press, administration, and law enforcement, Harvard and Yale athletics swiftly outlawed competition between the two schools for an entire year. The Game, known thereafter as a locus of violence and physical aggression, was not resumed until two years later.

#7: Pack the Bowl, 1920 (Harvard 9, Yale 0)

The 39th playing of The Game in 1920 was a joyful affair, coming off the heels of an Allies victory in World War I. With the war won and college football back in full swing, the Harvard-Yale rivalry was allowed to resume and did so with great enthusiasm and spectacle. The atmosphere must have been immaculate. What makes this edition so special is that the Bulldogs are reported to have hosted 80,000 fans in the Yale Bowl, the most ever at any contest between these two schools. The surely rowdy environment was fuelled by Crimson dominance, outrushing the Bulldogs and keeping Yale scoreless.

#6: Strangled Dog, 1908 (Harvard 4, Yale 0)

There are some stories in sports that are so wild, so far-fetched that there is simply no way they can be real — and yet, we can’t help but tell and retell them anyway. This is certainly the case with the incredible lore behind the 1908 Harvard-Yale showdown and the rousing pre-game address by Coach Percy D. Haughton, class of 1899. Stakes were high in New Haven as the Crimson sought to snap a six-year streak of losing The Game to the Bulldogs. According to the legend, Haughton, a future College Football Hall of Fame inductee, strangled a bulldog to death with his bare hands in front of his players prior to unleashing them onto the field. Whether or not a real bulldog carcass actually littered the ground of Yale’s away-team locker room does not matter. What matters is that Percy Haughton will be forever remembered as a coach dedicated to winning, no matter the sacrifice. And with that, it is worth noting that Harvard, in a possibly murderous frenzy, went on to defeat the Bulldogs and claim the national (yes, national) championship thanks to a well placed field goal from fullback Victor Kennard, class of 1909, in what became a truly legendary game.

#5: Harvard ‘Rips Yale To Bits,’ 1915 (Harvard 41, Yale 0)

The College Football Hall of Fame calls the Nov. 20, 1915 Harvard Stadium performance of three-time All-American Eddie Mahan, class of 1916, “one of the greatest individual performances of the game’s early history.” They might be onto something. In the 36th playing of The Game, Mahan, the Crimson’s captain put on an unforgettable performance, scoring four touchdowns and converting five extra points off the kick. Harvard won the game with authority, shutting out the Bulldogs. The 41 point margin is still the Crimson’s largest victory in the series. In response to the convincing win, the New York Tribune published an article titled “Harvard Rips Yale to Bits,” in which the author describes the battle as a “slaughter.”

#4: Vegas Odds Defied, 1979 (Harvard 22, Yale 7)

Sometimes the Yale football team just has a better year than Harvard. It happens. That’s sports. But as the great upset of 1979 shows so well, The Game is anybody’s to win. Going into the 94th Game, the Bulldogs were undefeated and untied. A 3-5 Crimson squad that had suffered a wave of injuries, including missing its first and second starting quarterbacks, was not seen as a spoiler threat. The betting odds on The Game favored the Elis by 13.5 points. Yet from the first kickoff to the final gun, Harvard owned the field. For a Crimson team which had experienced very little success on the offensive side, enough completions and rushes were strung together to become something almost magical. What Harvard really needed against this top rated Bulldog offense was an unbreakable line. The Crimson delivered a defensive clinic. Turning a Bulldogs’ first and goal from the four-yard line into a fourth-and-27, via back-to-back sacks, is just one example of the Crimson D-line’s highlight-reel level of play. As the clock ticked away at the max-capacity Yale Bowl, Harvard fans stormed the field and, in true college football fashion, ripped down the Elis’ goal posts. Some say we need more of this fan type of fan energy in this era.

#3: Post-Pandemic Last Minute TD, 2021 (Harvard 34, Yale 31)

Members of the Class of 2025 who were lucky enough to trek to New Haven for the post-pandemic Harvard-Yale series revival — the 137th playing of The Game — were treated with one the most exciting college sports moments in recent memory. The Game was a tight contest throughout, and though the 50,000-strong crowd battled a bitter chill, the roaring energy of the crowd provided more warmth than any coat. The iconic sequence that made the 137th Game an instant classic was the Crimson’s do-or-die drive to come back from behind and secure the win. With less than a minute left on the clock and Harvard down four points, a miracle touchdown needed to happen. Backup quarterback Luke Emge ’23 and star wide receiver Kym Wimberly ’23 proved to be the fire that the Crimson needed. The 37-second-long drive moved Harvard 66 yards down the field, thanks to a 42-yard missile that Emge launched to guide Wimberly to the Bulldog 12, setting the team up for a crucial strike. With third and 10 for Emge and 22 seconds remaining, the quarterback lofted a ball over a tight double team of defenders to find an acrobatic Wimberly in the end zone. The crowd went berserk, and naturally, the field was flooded with enthusiastic away-team fans.

#2: Triple OT, 2005 (Harvard 30, Yale 24)

The longest game ever played at the Yale Bowl (and in Ivy League history) saw the Crimson and Bulldogs clash for almost four hours in New Haven. Though Yale led 21-3 in the third quarter, the Crimson was able to mount an impressive comeback to force The Game into overtime in front of an exuberant crowd of 53,000. With the game at a standstill, 24-all, and the level of play increasingly affected by fatigue, the conditions were perfect for a hero to emerge. And of course who better to save the day than Harvard record holder Clifton Dawson ’07. With the Crimson set up for a golden opportunity on the Bulldog two-yard line, Dawson was trusted to make his 258th season carry. The running back plowed through the Elis defensive line and secured the long-awaited victory for Harvard.

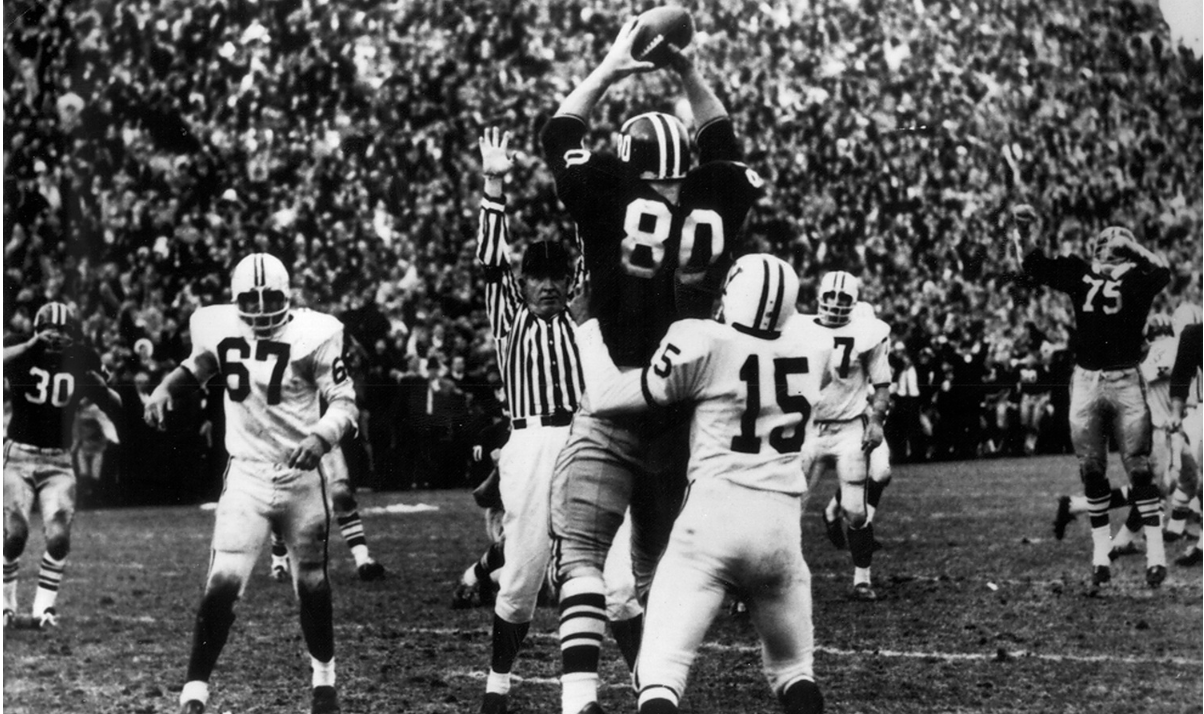

#1: 16 points in 42 Seconds, 1968 (Harvard 29, Yale 29)

Most sports fans are familiar with the iconic story of Tracy McGrady scoring 13 points in 33 seconds to propel the Houston Rockets over the San Antonio Spurs during the 2004 NBA season. In 1968, the Crimson pulled off its own T-Mac performance, cashing out on 16 points in the final 42 seconds of play to even the score with the Bulldogs and force a draw. An incredible statline to find in any football game, nevermind The Game, the final sequence of drives from the men of Harvard is surely one of the greatest of all-time. Down by an impossible margin of 16 with under a minute of play, quarterback Frank Champi ’70 found right-end Bruce Freeman ’71 open with enough space to jog into the endzone for a Crimson touchdown. A two point conversion suddenly made the impossible seem merely improbable. A bold onside kick resulted in a Yale fumble. Harvard recovered the ball. The subsequent drive is history. Bringing his team all the way to the Elis’ 6, Champi had a chance at greatness. Taking the snap under intense pressure, the quarterback dodged and danced around the 15 yard line. Just as Champi was decked by a Bulldog defender, he threw up a prayer towards running back Victor Gatto ’69. With time expired, Gatto reeled in the catch and, in spectacular fashion, fell backwards into the endzone. And having come this far, a two point conversion was inevitable. Champi located Pete Varney ’71 in the endzone and dropped him the ball. Though the game ended in a tie, the Crimson was declared to have won this contest 29-29 by all onlookers owing to the strength of its Houdini-like escape from defeat.

—Staff writer Callum J. Diak can be reached at callum.diak@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.