News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

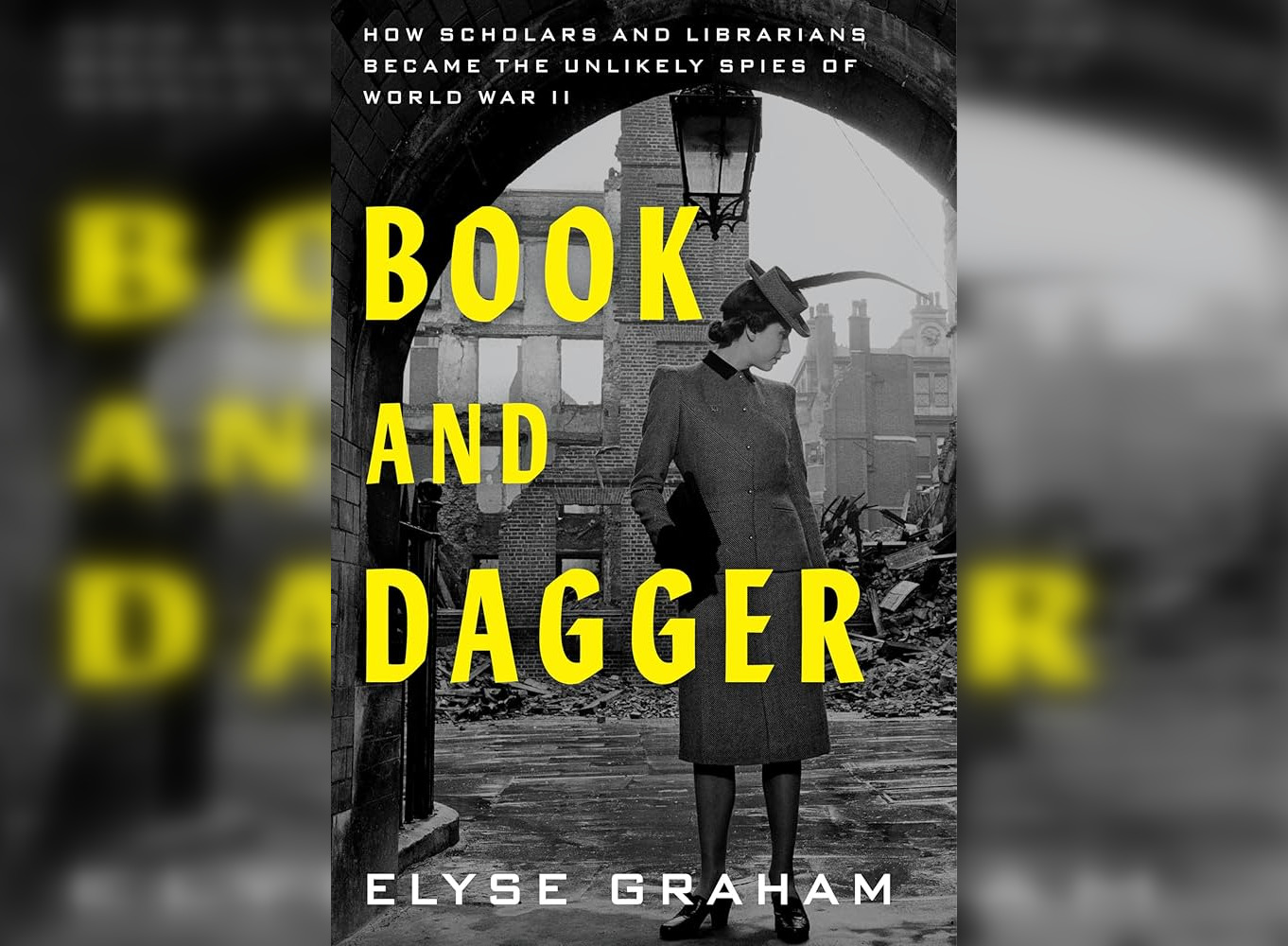

‘Book and Dagger’ Review: How Readers Rewrote Espionage

In her fourth book, “Book and Dagger,” author Elyse Graham describes history’s widespread coverage of D-Day, writing: “Here’s the war that everyone saw — the war you’ve heard about.” This faux opening line surprisingly falls toward the book’s denouement, which fittingly discusses the dangers of trusting an uncontextualized quote as reliable intel. “Book and Dagger” instead delves into everything outside of that description, examining the overlooked and amplifying the unheard to spotlight the key contributions of humanities scholars to fledgling espionage tactics that ultimately won the Second World War.

Graham, a historian and professor of English at Stony Brook University, weaves a timely and compelling nonfiction narrative that glamorizes the often-neglected topics of analog archival research, waiting games amidst the global rat-race for information, and the continuing relevance of a liberal arts education. She does all of this within a writing style mirroring spy fiction that tends to favor the flashy and fast-paced. “Book and Dagger” accomplishes this feat by crafting an imaginative and cinematic experience rooted in real-life, characterized by an immersive blur between fiction and nonfiction.

While this book launches into a rocky start with mishmashed character introductions of awkward length, it soon finds its footing by kicking into a higher gear of rapid-fire historical references and descriptions of espionage. Graham details the recruitment, training, and activation processes of four featured characters: Joseph Curtiss, a Yale English professor; Adele Kibre, an archivist with a Ph.D. in Latin from the University of Chicago; Sherman Kent, a Yale history professor; and — to a lesser degree — Carleton Coon, a Harvard anthropology professor. Each figure’s personality quirks and motives for espionage are thoroughly explored with plenty of Graham’s own commentary. For instance, Graham expresses disdain toward Coon’s pseudoscientific, racist views. This commentary provides an additional layer of intrigue to Graham’s already-riveting narrative.

Through episodic focus on each scholar’s unique skills, like Kibre’s experience tracking down inaccessible texts and preserving their contents, “Book and Dagger” highlights how well-suited academics are to intelligence work. Graham details how these scholars — fine-tuned for crafting key questions, chasing clues through manuscripts, and dissecting overheard minutiae — produced breakthroughs for Allied intelligence and, through another well-honed skill of teaching, laid the foundation for the CIA’s eventual creation.

While its content is intriguing and underappreciated, the hallmark of the book lies in its narration. Graham encourages readers to employ the tactics of “Book and Dagger” characters through deft writing that simulates free-flowing gossip. The prose underscores the thematic significance of whispers throughout the book. Brief sections keep readers engaged through a patchwork of narratives, titled with plenty of spy-fi puns for loyal fans of the genre.

For newer fans, Graham familiarizes the techniques of espionage in layman’s terms. Graham facilitates imagination with second-person narration — such as a chilling description of a plane crash unfolding in real time — and fills in gaps of the historical record with her own dialogue and action. While this latter choice makes for a clunky use of shifting tenses and creates some confusion between truth and embellishment, Graham herself acknowledges that “playing a game of information asymmetry often means accepting the unknown.” Nevertheless, Graham encourages readers to push further into this unknown through critical thinking, offering helpful and explicit lines of questioning like “How did he reconcile his crimes with a scholar’s cozy existence?” Much like the book’s frequent setting of Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar, so much education and entertainment is packed into one place — captivating readers and forcing them to grapple with the issues presented.

Graham’s commentary on the mid-20th century contains lessons for today, underscored by a healthy sense of humor. “Book and Dagger” argues that American intelligence’s strength resulted from its openness towards new and unconventional ideas and backgrounds, stating in characteristic levity: “It’s the American way: welcoming strangers, seizing the practical gains of diversity, finding common course between aristocrats and thieves.” However, Graham also uses this platform to discuss America’s shortcomings in welcoming — and remembering, even decades later — minorities such as Lise Meitner, a female physicist whose nuclear fission research Otto Hahn took credit — and a Nobel Prize — for.

These remarks appear particularly pertinent during an election year amidst discussions on national identity and security, but Graham furthermore builds upon a millenia-old debate on the relevance, opportunities, and worth of studying the humanities. “And yet we also belong, in the twenty-first century, to a time of profound disdain for the humanities that is prompting us to turn away from the very fields that this book has shown are so important,” she writes on the second-to-last page — the real culmination of the book. Through her masterful commentary and gripping narrative, Graham clearly shows that artists can produce both economic value and political power with far-reaching, world-altering gains.

—Staff writer Jackie Chen can be reached at jackie.chen@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.