News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

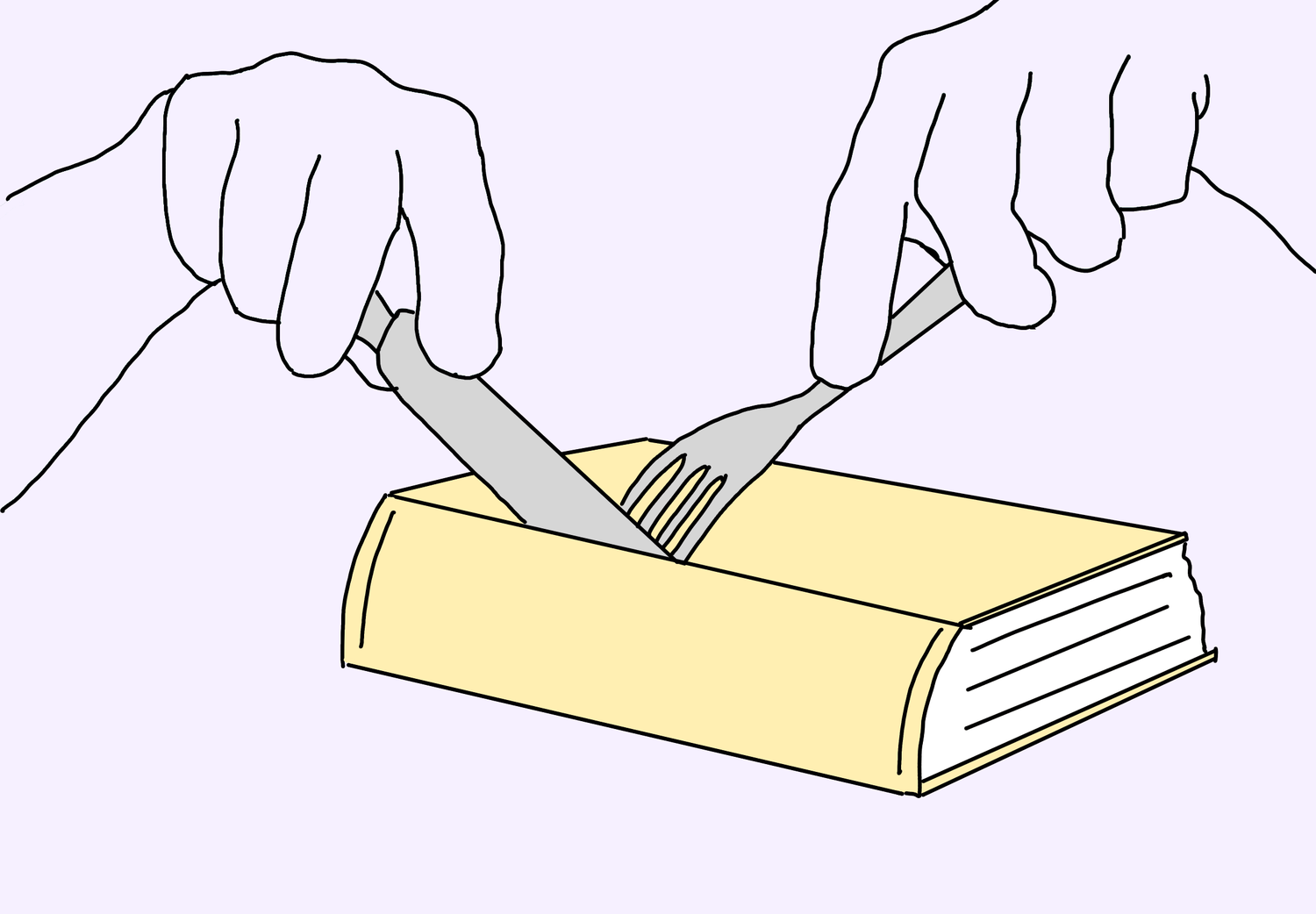

Stop Consuming Art

Humans are eating art, though not in the literal sense.

Consider the word “consume.” Modern creative culture has facilitated a shift in interaction with media, and it can be seen through something as simple as this linguistic denotation. Creative works are no longer just read, watched, or listened to. They are often referred to as “consumed.”

The public is devouring the creative sector with a heedless appetite, and the industry is changing rapidly to keep up with the demand. The desire to consume is changing artistry. It’s hurting art.

Examples of the new hybrid art and economic world surround consumers. “Van Gogh Exhibit: The Immersive Experience” advertises: “Have you ever dreamt of stepping into a painting? Now you can with this exhibition that has been touring since 2017 with +5,000,000 visitors!”

By 2022, the project sold about 4.5 million tickets and accumulated approximately 300 million dollars of revenue from gift shop sales and tickets for the exhibit and special events like yoga under the projected stars. The market made it possible to turn a renowned painting in a museum into a projection and occasional quasi-yoga studio — and make a lot of money from it.

Creativity is a commodity in our day and age, but it hasn’t always been that way.

Industrialization marked a change in thinking about products. Humans could make more, buy more, and use more. Anything could be marketed, including art. ‘The creative economy’ specifically was introduced in the 1960s as a term encompassing the production, innovation, and social capital connected to arts and culture. The global creative economy is estimated to be worth $985 billion and is projected to account for 10 percent of global GDP by 2030.

Anyone on social media knows what commercial content creation looks like. There’s a game to achieving popularity online, and the content itself is mostly mind-numbing and rarely insightful. Even still, it’s highly valued — an influencer with around 100,00 followers on Instagram can make approximately $670 per post.

In the fast-paced environment of online platforms, popularity is the prize. If a creator can produce a lot and do it quickly, their chance of recognition is higher, even if the quality of their work has to suffer for it. Virality is not a demarcation of value, but it is a good thing for business.

Artists have to make a living, but the pressure of a commercial environment can devalue taking creative risks because it rewards those who follow mainstream trends or produce faster. When a consumer spends a fraction of their time observing something as it took the artist to create, it doesn’t take that artist long to realize they can save time while making money if they create more rather than better. It sends a clear message.

In his book “Saving Beauty,” Byung-Chul Han discusses the modern condition using the term “smooth culture.” He characterizes this trend as the recently developed craving for speed and perfection in all aspects of life. Humans now want fast-paced experiences rather than enjoyment in surprises and slow peculiarities. They want to touch, take, and devour; they want to have something over observing and appreciating it. They want smoothness. The idea resonates when one stops to think more deeply about the Van Gogh Immersion.

That smooth sense of speed is the driving force in multiple industries now. Again, it’s in the semantics. Fashion has become “fast fashion” and food has become “fast food.” Of course, it’s a two-way street — industries impact people while people impact industries, so no one party is entirely to blame. With what agency the consumer does have, it’s worth pausing to recognize the pattern. The fastest possible world may not be the best possible world.

The trajectory of the modern age isn’t all negative for the creative realm. Technology and tools for mass media aren’t inherently a limitation — it’s rather how we use them that can become problematic.

Democratizing art isn’t a bad thing either. Means of accessing art, like new media platforms or even exhibits like the Van Gogh Immersion, can break down class barriers built into the artificial concepts of ‘high’ or ‘low’ art. Widespread consumption of art can help progress equity. It would be great to see more educational projects explicitly intended for that over money.

On the day to day, consumption in the arts is perpetuated by a growing tendency to value the proof of experience over experience itself. It’s easy to see in any museum lately. People are hungry for a picture of a painting to post over spending a few moments actually looking at it, and that’s no shock given the average human attention span is down to under nine seconds. It’s not very surprising, but it doesn’t have to be the new norm.

The art world isn’t changing itself; it’s changing because people are changing it. Just as the public chooses to consume art, it can choose to appreciate, contemplate, protect, and share it.

It’s worth being an engager rather than a consumer, if not for the sake of preserving an attention span then for the sake of retaining something core about being human in a world constantly demanding our money and time. It is possible and valuable to partake in the market differently, knowingly. Seeing this danger gives space for avoiding it and there are creators to support out there on every platform who are making art to engage with, not to devour. Engage with it.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.