News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

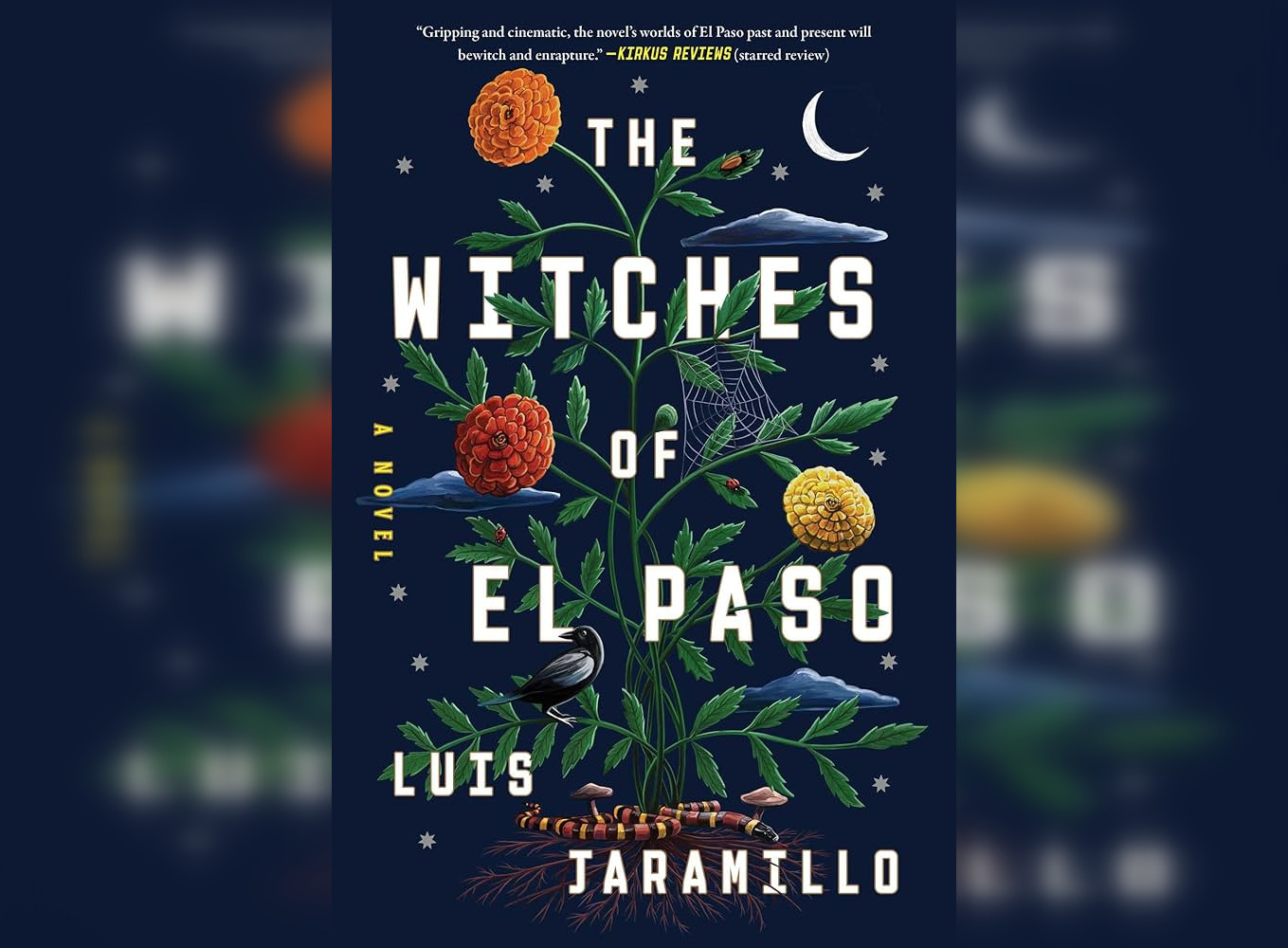

The Witches of El Paso Review: Magic and Reality Muddle the Message

3 Stars

“The Witches of El Paso” is a novel about migration — across time, space, people, and countries. The characters, the most substantive of whom are women, are thrust into the 18th, 20th, and 21st centuries from Mexico to the United States and back. Reckoning with indigeneity and displacement, their identities shift along with time and national boundaries. In this epic whirlwind Luis Jaramillo constructs, possession and power emerge as central themes, with the women’s agency challenged by the conventions of the different historical periods they inhabit and by the all-consuming magic that threatens their autonomy. For most of his debut novel, Jarramillo employs tired tropes to elegant effect, completing an ambitious routine of literary acrobatics — juggling fantastical elements and trapezing from one time period to another. At the end though, he fails to stick the landing.

The narrative centers on the transport of Nena — an 18-year-old woman of Latin and Indigenous descent — from 1943 Texas to 18th century Mexico, where she is a child possessing “La Vista” or a chaotic magic. After discovering her power, Nena unwittingly answers the call of a convent of nuns with similar powers who vow to train her to master them. At the convent, she laments the restrictions on her freedom, cures those suffering from smallpox, falls in love with a man betrothed to a fellow student, and leaves their child behind in the 18th century when she finally returns home to the 20th. With the exception of the smallpox epidemic that feels extraneous, Jaramillo’s plot points discerningly interrogate both 20th and 18th century societal restrictions on women’s autonomy.

Moreover, the security of the convent ostensibly allows Nena to master her magical powers, but simultaneously imprisons her; her love affair frees her from sequestration in the convent and from the monotony of domestic life in the 20th century, but she is barred from the joy of marriage and motherhood because of her class. A complex tension emerges over whether Nena possesses her lover, her daughter, and her magical ability, or whether they possess her.

Masterfully intertwining Nena’s fantastical narrative with a more contemporary narrative concerning Marta, Nena’s grandniece, Jaramillo alternates between the perspective of Nena and Marta in different chapters to toggle effortlessly between time and space without the reader ever becoming disoriented. Commendations are certainly in order to Jaramillo for his controlled handling of a plot as chaotic as “La Vista” itself.

Marta, like her great-aunt, grapples with oppression and magic. A lawyer building a case against a wealthy businessman who sexually harassed female employees from disadvantaged backgrounds, Marta is at first rational and dismissive of Nena’s magical ability. At the beginning of the novel, Marta delivers her assessment of magic while looking upon her disadvantaged client clutching a pendant with the evil eye: “Magic, or the idea of it, is a way for the powerless to imagine they can become powerful,” she sighs. Marta prefers working within a system to defy oppression — in her case, the legal system — even if the plaintiffs are so disadvantaged that they must resort to imagination to have any hope of victory.

In contrast, Nena, first trapped in the tedium of her role as her sisters’s nanny and then in the convent as a woman without rights who cannot marry the man she loves, harnesses magic to break free of oppression. Even as she is pitched about from one century to the other, she states that she is “free inside my head.” No longer is Nena a “toy,” but “a witch.” Magic allows her to reject systematic discrimination, resulting in the touching triumph of a woman of color and a stunning indictment of a world that demands magic for any freedom to be achieved for women like Nena.

This conclusion about the shortcomings of the U.S. justice system, grounded in the present day, is by far the most significant of the novel. Yet, the fact that Marta, who unlocks “La Vista” by the end of the novel, fails to have any epiphany about systemic change in the United States feels deeply unsatisfying. The novel’s criticisms of sexism do not feel sufficient for a novel set in multiple timelines as it attempts much more than historical fiction. If the reader grants Jaramillo permission to time travel and play with magic, one would hope he would eventually return to commentary significant to reality. Instead, hurled every which way, the plot devices have dizzied the message. The narrative ends with Marta realizing she is pregnant, which parallels Nena’s pregnancy earlier in her life, but does not allude to any of the other central themes. Ultimately, “The Witches of El Paso” squanders its potential to create insight relevant to its contemporary society, its purpose becoming as muddled as its timeline.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.