“Sea Monsters” Exhibit Blurs Border Between Monster and Human

In novels like “Moby Dick” or “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea,” monsters exist to aggravate and impinge on human life. Science, folklore, and fiction have villainized deep sea creatures for centuries, suggesting that humans should fear their existence.

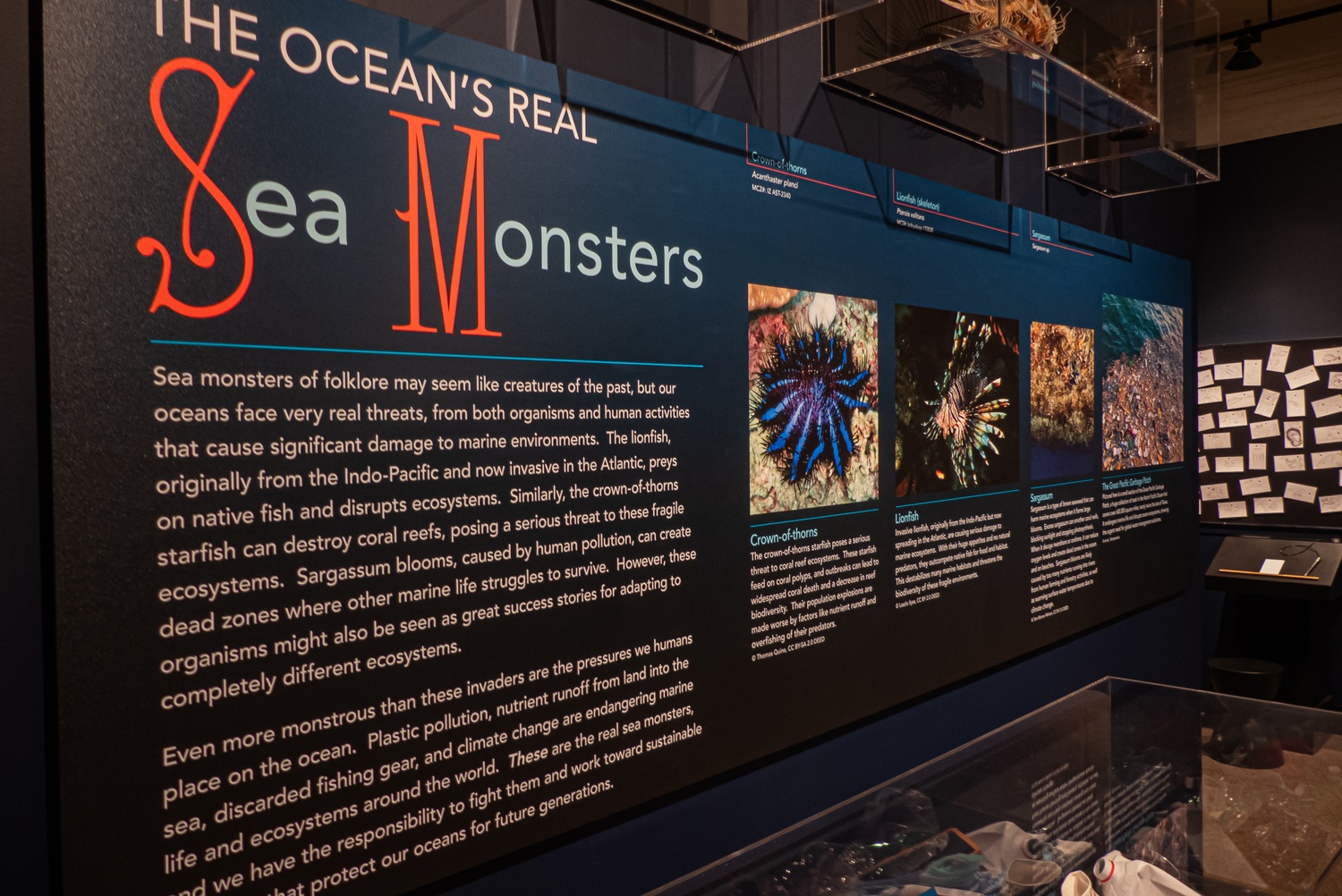

On the third floor of the Harvard Museum of Natural History, the “Sea Monsters: Wonders of Nature and Imagination” exhibition, opened in June, offers evidence that the real monsters cannot be found deep in the ocean or in the human imagination. Through the juxtaposition of different sea creatures and their relationships to a polluted environment, “Sea Monsters” asks visitors to consider how human-induced climate change might be the true monster deep beneath the waves.

Ocean-blue walls surround the exhibit, transporting visitors into the sea and traversing the boundaries between humankind and sea monsters. Maps with depictions of sea monsters cover the walls and position visitors as navigators.

“We want this exhibit to give people, including children, a chance to think and decide for themselves,” says exhibit curator Peter R. Girguis, a professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology.

In one display titled, “Not So Big & Scary!” the menacing names of a sea creature are contrasted to their actual sizes. For example, the deep sea viperfish is less than six inches long, and a common fangtooth is seven inches long.

“I’m not asking everybody to fall in love with the viperfish,” Girguis says. “But I think it’s important to understand that they are legitimately no threat to you or anyone, and that, I hope, changes people’s relationship with these sea creatures, as well as with the ocean in general.”

Girguis’s curation highlights how human fears and insecurities are personified through the names and media portrayals of creatures. “Sea Monsters” allows individuals with varying interests to reflect on their perception of the ocean and its creatures.

Though sea monsters are often imagined as frightening and unknowable, Girguis says they’re not.“To us, they look sinister and strange. But I would like to think that if they could look at us, and have thoughts about us, that they’d say, ‘Oh, those humans look really bizarre.’ It’s all relative to our own experience,” he says.

A glass case filled with plastic, fish nets, packaging, bottles, and other waste washed up from the sea is labeled with a question: “Who Are The Ocean’s Real Monsters?” This display poses the question of whether humans attach the “monster” label to creatures who actually do the most harm.

“We’ve played a big part in the impact that invasive species have around the world,” Girguis says. “Climate change is the biggest sea monster, and the second-biggest sea monster is plastic pollution, because we don’t do this with the full knowledge of how problematic plastics can be.”

Ultimately, “Sea Monsters” displays that “humans should always be reckoning with the implications of their actions,” Girguis says.

Humans have created their own fantastical conceptualizations of deep sea creatures by characterizing them through terrifying names and intergenerational mythologies. “Sea Monsters” lets visitors see “that the animals that inspire sea monsters are not monstrous at all,” Girguis says. “The sea monsters are personifications of some of humankind’s worst attributes.”