News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

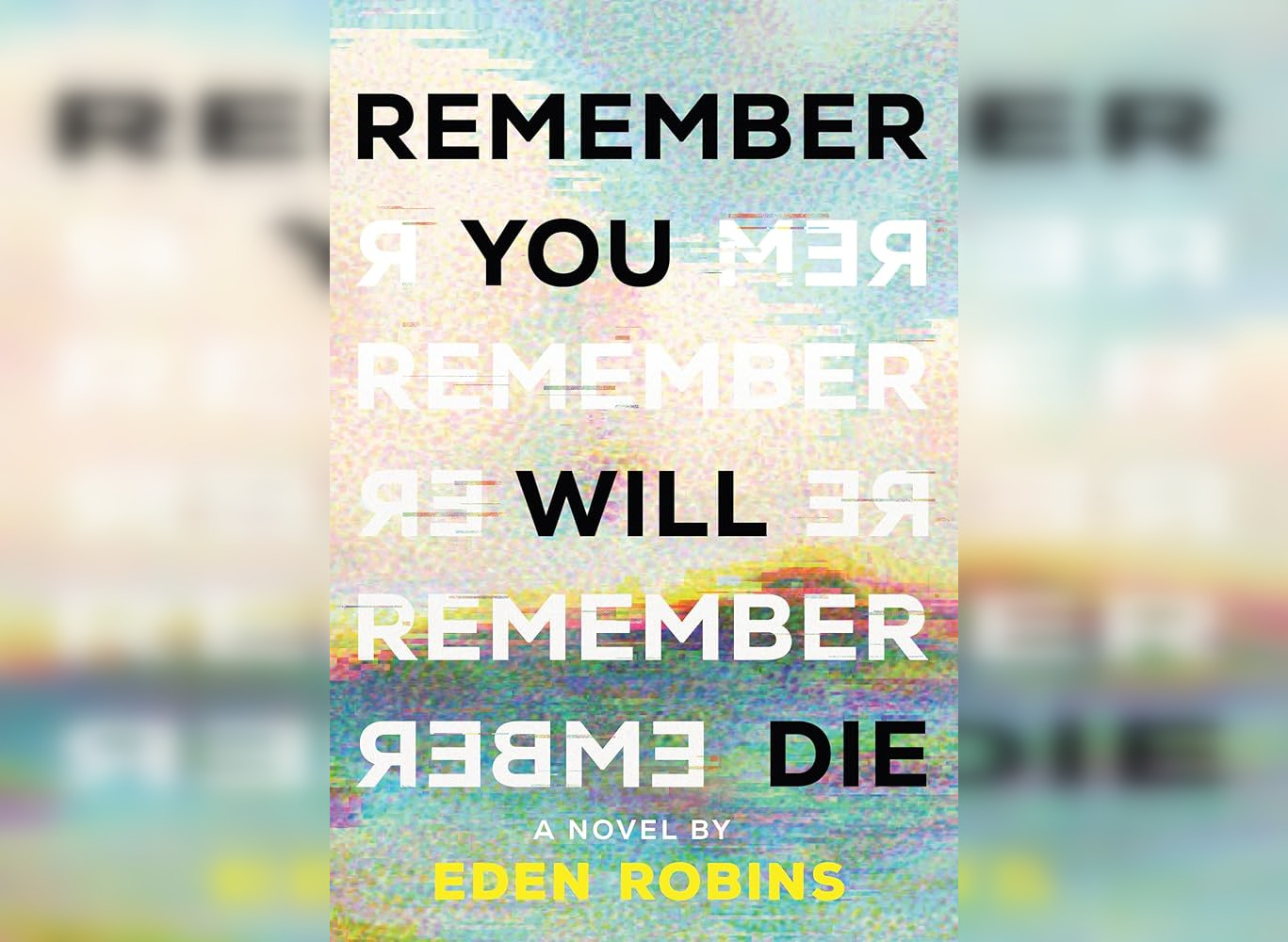

‘Remember You Will Die’ Review: A Bold, Yet Disjointed Confrontation of Death

2 Stars

Warning: This review contains spoilers.

“Remember You Will Die” is a genre-bending novel that explores the interconnectedness of grief, death, and humanity. Written by Eden Robins, an essayist and the author of “When Franny Stands Up,” this ambitious novel delineates a story about an AI mother, Peregrine, mourning for her human daughter, Poppy, through 60 obituaries dated between the 19th and 22nd centuries. “Remember You Will Die” revolves around the central message of what it means to be human in a posthumanist world. However, the bold structure of the novel distracts the narrative from its central focus, resulting in a bland and fragmented work.

Told through obituaries, word etymologies, newspaper articles, and occasional notes, “Remember You Will Die” defamiliarizes lives, names, and events into plain reports, encouraging readers to piece together the real emotions that lie beneath the pages. The novel begins with a brief news report on Poppy’s suicide in 2102 and immediately turns to defining the poppy flower as a symbol of war deaths. In the 60 obituaries, some characters reappear in several accounts, including Peregrine, her Frankenstein-esque creators, and Poppy, who was conceived by human eggs frozen from the 20th century, a donated human uterus, and human skin cells turned into sperm.

As the novel progresses, readers gradually find out more about these characters, their donors, creators, families, and friends. By the end of the novel, readers can piece together a puzzle of stories and find out how they interconnect. These fragmented accounts encourage readers to contemplate the ephemerality of life: A person can be alive on one page and can be dead on the following. Telling these stories through obituaries is inherently macabre and poignant, as the main character in each story is no longer alive.

Although a central storyline about Peregrine and Poppy persists, the novel lacks character development due to its fragmented narratives and defamiliarized contexts. Each vignette is too detailed and casual to read like a real obituary, yet too fragmented to compose a coherent narrative. Its generally bland tone makes readers unable to access most characters’ thoughts, motives, or emotions. While Peregrine is one of the few characters who speaks about her feelings, her interiority is scattered and fragmented. Between Peregrine grieving for Poppy’s death to her eventual acceptance, readers can hardly parse through any changes in her emotions due to the lack of a consistent trajectory. With its plain tone, complicated network of characters, excess of stories, and lack of character development, the novel struggles to engage readers.

Moreover, the novel does not provide the rationale necessary for readers to understand the context and leaves many questions unanswered. How does one even fall in love with an AI? Why are humans suddenly on Mars? Can 3D-printed organs function in a human body?

Robins also rewrites the story of Anne Frank in the novel, as she explains in “A Conversation with the Author” at the end of the book. Robins’ version of Anne Frank survived the Holocaust, emigrated to Chicago, and had a daughter — named after her historic sister Margot — whose eggs are later used to conceive Poppy. This episode is bluntly inserted into the novel with no explanation, easily leaving readers confused. Rewriting the tragic death of a historic individual complicates the plot and message of the novel, although Robins described it as an “extremely liberating” experience.

Overall, the novel attempts to explain the context of this posthumanist future but creates more confusion and questions than answers. While the element of surprise can advance the plot in some cases, the overabundance of them in this book — which already lacks a central plot — simply reads absurd and confusing.

Nonetheless, all the loosely related stories are connected via one theme: “Death is final.” All human experiences, innovations, arts, and troubles that the obituaries document will cease to exist upon one’s death. Peregrine eventually lets go of her grief for Poppy. Readers eventually learn that Poppy faked her suicide to escape from Peregrine. The novel comes to an end at a poignant call to embrace escaping, leaving, and ending.

Still, much of the novel reads as if it is forced into such poignancy. Grandiose and abstract statements about death and humanities appear throughout the bland and overly detailed obituaries. While Robins may have aimed to create an ambiance of sorrow and empathy, these statements are disjointed from the tones of the obituaries and excessive.

Ultimately, Robins’s attempt is bold, creative, and applaudable. She embarks on an ambitious task of documenting human experiences through an untraditional format that defies the categorization of literature. “Remember You Will Die,” as its title suggests, serves as a memento mori that makes insightful comments about how one should confront death and mortality. However, the book aims to combine too many adventurous decisions into just over 300 pages. Nonetheless, it still makes a thought-provoking literary puzzle for readers to solve.

—Staff writer Xinran (Olivia) Ma can be reached at xinran.ma@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.