News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

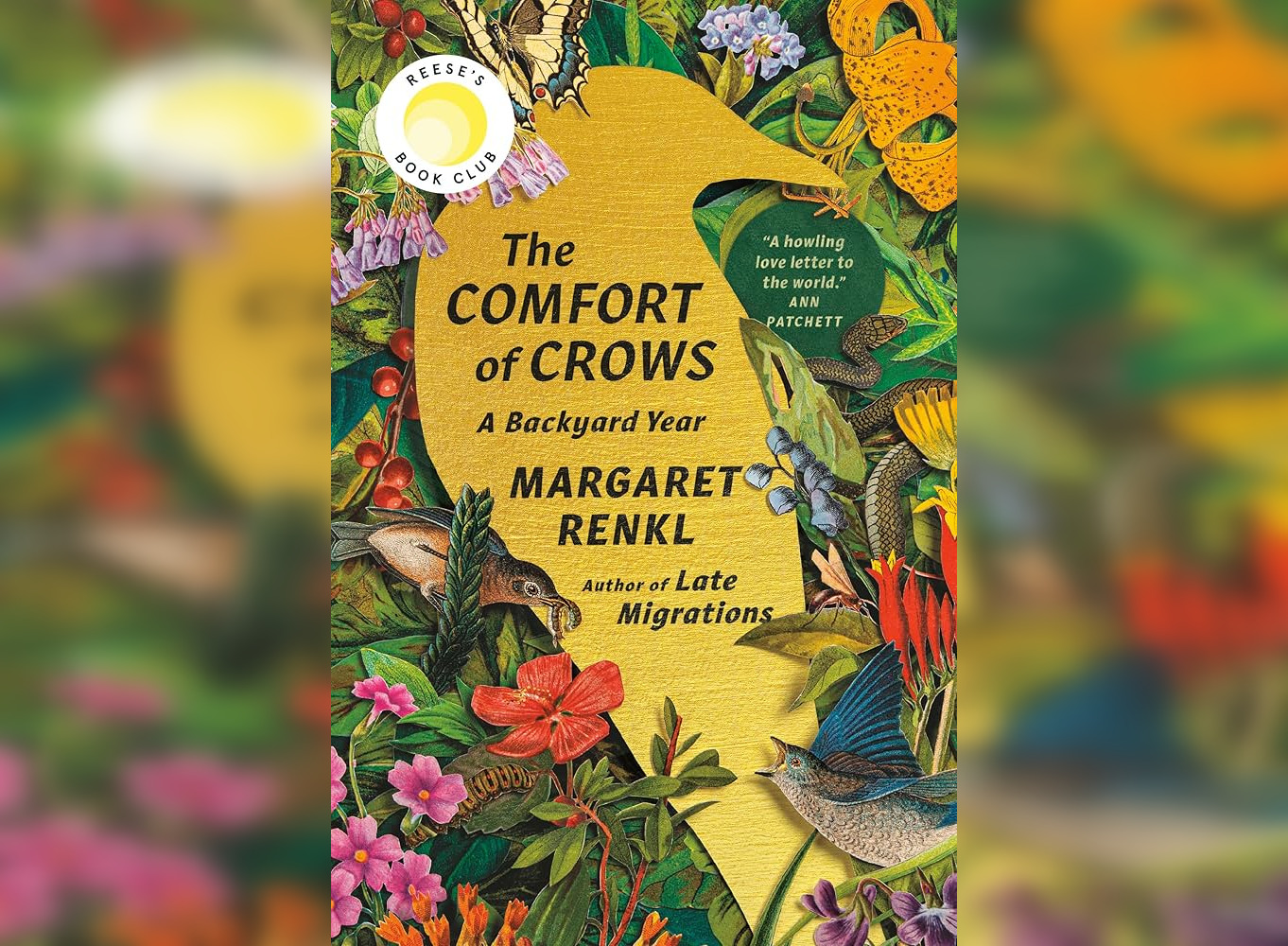

‘The Comfort of Crows’ Review: Masterfully Reintroducing the World as We Know It

4.5 Stars

In a daunting 52 chapters, one for each week of the year, Margaret Renkl’s book “The Comfort of Crows” takes readers through a year of change surrounding her home, both inside and out. The book represents a deeply personal approach to nature documentary and inspires readers to embark on a similar journey through their own backyard. The scrapbook-like combination of beautiful illustrations by Renkl’s brother, Billy, and quotes from various authors or poets supplement the emotional prose to create a lengthy but brilliant masterpiece.

The book is organized into four sections, one for each season, and curiously begins with winter, the season usually associated with endings. In spite of winter’s chill, Renkl rejoices in its delicacy, asking, “who could fail to embrace a season so beautiful and so fragile?” This positive spin on winter is opposed by the heartbreaking stories of the summer — three baby bunnies unfortunately die under her care. The juxtaposition of the beautiful fragility of winter with the frailness of the baby bunnies and summer deftly reveals the underlying tone of the book: the never-ending cycle of life and death.

While Renkl does directly discuss deaths, such as of various wildlife and even neighbors, she also weaves in meaningful commentary on other significant endings. Written over the course of three years, the book covers the passing of her father in-law, reflections on becoming an empty nester, and, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, her children briefly moving back in. The bulk of the book relays Renkl’s deep reverence for all life around her and the care she employs, but readers also get a glimpse of the author in the reverse role as a daughter when she recalls her mother’s method for contending with “wintertime blues” or how she used to play as a girl.

Including anecdotes about her childhood perpetuates the cyclical nature of the book and life itself. The amount of detail Renkl recalls about her feelings or an afternoon outside is the same amount of detail given to the myriad of wildlife creatures she encounters, uplifting her central theme of the cyclical nature of all life on Earth.

Along with mentions of her mother and children, the book mentions her husband and her dog, but only by their names — it is as if Renkl is writing a journal rather than a book. Furthermore, she uses specific terminology, such as “mast year,” and writes as though she is speaking which both allow readers to peer into her life as a mother, author, and lover of the environment.

However, this style of writing could create initial confusion for readers who might, for example, assume Haywood to be her dog. Niche terms like “mast years” may stump readers unfamiliar with the life cycle of trees. While the journal-like diction of this book relies on many prior knowledge assumptions, Renkl expertly includes small details that give readers most of the necessary background information, exemplifying her skill in writing prose.

Renkl begins the book subtly in second person with the foreword serving as a guide for contemplative observation of the world around “you.” As though giving instructions, Renkl writes, “Stop and peer at the hummingbird next, smaller than your thumb, in the crook of the farthest reach of an oak branch.” She continues this pattern of guiding readers through a hypothetical nature walk, powerfully ending with a simple suggestion on how to re-establish a connection with our environment: “we are only obliged to look.” In this manner, Renkl uses point of view to engage on a deeper level with the reader.

In addition, Renkl directly calls to younger generations, addressing her relationship with her cell phone. In an active effort to resonate with a younger audience, she writes, “I can scroll and worry indoors, or I can step outside and remember how it feels to be part of something larger, something timeless, a world that reaches beyond me and includes me, too.” All readers are forced to reckon with the impact of social media on our relationship to the smaller, not global world — that of our own backyard. This especially applies to younger readers growing up in the digital age, constantly bombarded with conflicts from around the world. She seems to say that, for them, finding solace in their own natural surroundings offers a unique peace.

“The Comfort of Crows” dives deep into what it means to be alive on multiple levels: physically alive, as a human, an animal, a plant, and alive with hope. The charm of this book cannot reverse climate change or end deforestation, but it serves as a glimmer of hope amidst a bustling world. Renkl’s vulnerability with her readers and her environment is excellently expressed through her moving anecdotes and implicit advice on how to proceed in the face of such a harsh world. Renkl’s dedication to observing her place, and humanity’s place broadly, in our ecosystems crafts a powerful call to venture beyond the front door and absorb everything their own backyard has to offer.

—Staff writer Madelyn E. McKenzie can be reached at madelyn.mckenzie@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.