Is the Bio Lab a “Nobel Incubator?”

This year, Victor R. Ambros and Harvard professor Gary B. Ruvkun won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering microRNA. With this year’s prize, they join 10 other Nobel laureates who have also worked on the third or fourth floor of the Biological Laboratories, a brick building tucked within a quiet area in the northern part of campus that houses many research labs.

To Molecular and Cellular Biology professor Richard M. Losick, this is no accident. He thinks an intense culture focused on scientific excellence has resulted in the Bio Labs becoming a “Nobel incubator” — a place that helps develop “bold thinkers.”

For years, Losick has worked to publicize the legacy of the space. He published an article on the MCB website about it and drafted an ebook about the history of molecular biology that includes Bio Labs’ role.

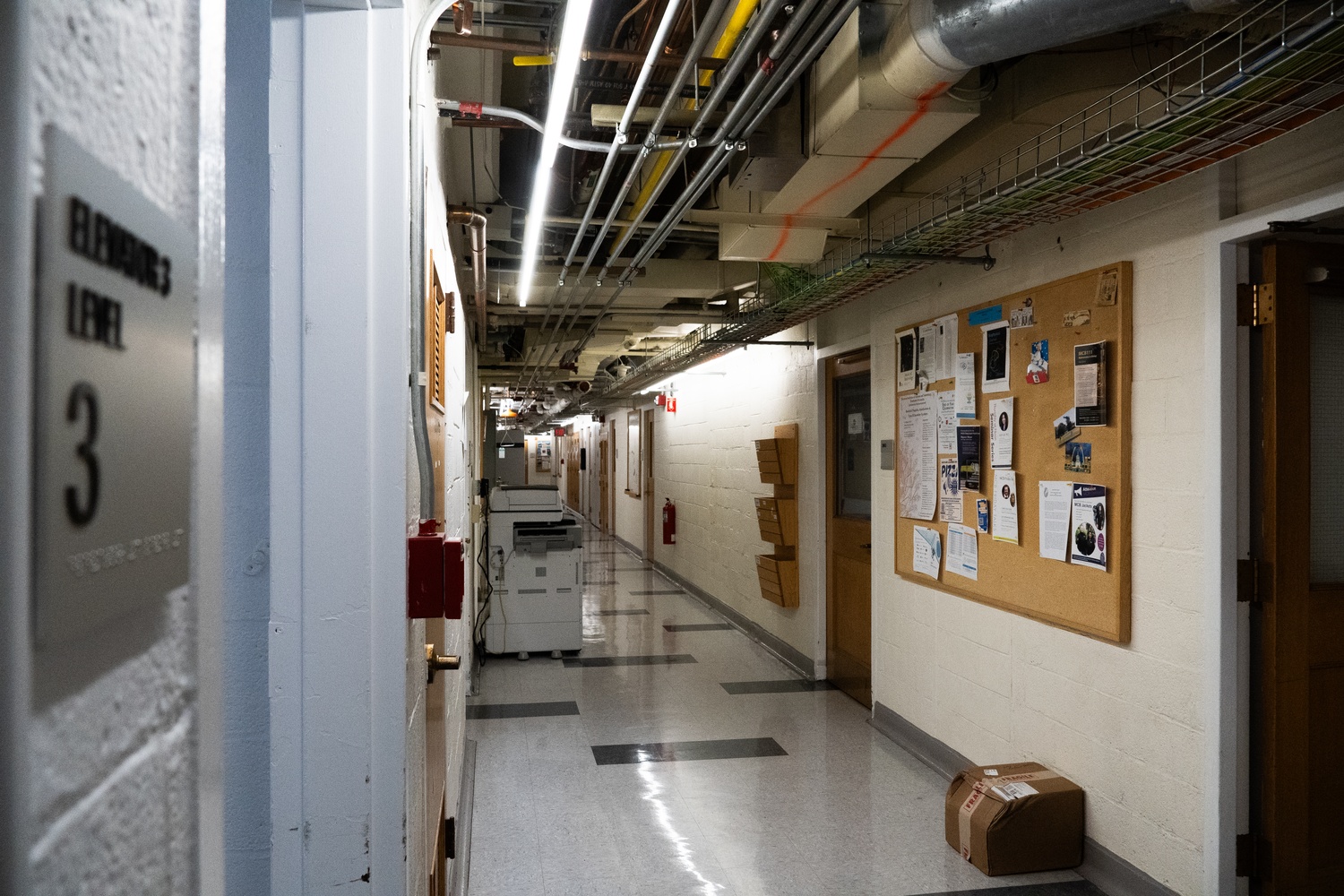

To our eye, the third and fourth floors of the Bio Labs look like a pretty standard laboratory — copper wires and metal tubes run along the ceiling, Revco refrigerators hum ambiently, and behind glass doors, researchers work diligently. A few pass us carrying tubes ready for the centrifuge.

But to Losick, who has called the third floor home for 55 years, the white cement corridors hold a legacy. As he gives us a tour of the space, his personal investment in this history shows. “The field is young enough and I’m old enough that I lived through it,” he tells us.

As we walk down the hall, he points at researchers now standing in the spaces where the pioneers of genetics once stood.

Losick traces this legacy back to Nobel laureates James D. Watson and Walter Gilbert. Watson received the 1962 prize in medicine or physiology for the discovery of helical DNA structure. Gilbert won the 1980 prize in chemistry for his work developing methods to sequence DNA. The two shared a laboratory in the 1960s and, according to Losick, created an intense culture in the Bio Labs.

“It was a sink or swim. It was a very intense, competitive, even bullying. I mean, it wouldn’t be tolerated these days,” he says.

Losick smiles fondly, though, as he recalls the environment. “It was tough, but on the other end, it was inspiring,” he says. “What was special about it was that there was this culture of asking big questions.”

But now, Losick says of that culture, “it’s gone.” According to his colleague Mario Capecchi, who won the Nobel Prize in 2007, working 90-hour weeks used to be the norm, but Losick says that is no longer the case.

“The Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology celebrates our students, postdoctoral fellows, and faculty for their accomplishments big and small, from winning Nobel Prizes to everyday discoveries in the lab and classroom,” wrote Molecular and Cellular Biology professor Rachelle Gaudet in an email statement. “I am grateful for the opportunity to work with people who are at the cutting edge of their research fields and who support and push each other to ask important questions and develop and implement state-of-the-art technologies to make exciting discoveries.”

As we continue along our tour, Losick stops by a blank wall outside room 3075. It once held a plaque commemorating Watson.

Losick points out the four dents that once held up the plaque, which he arranged to be put up after Watson visited him in his office. At the time, Losick was the chair of the department, and Watson had dragged him down the hallway asking where his recognition was.

The plaque was later removed for remarks Watson made, including that white people were genetically smarter than Black people, that women were “less effective” scientists if they had kids, and that if a gene for homosexuality was found, parents should be allowed to abort their child for that reason.

“I don’t think my view is that of the University’s,” Losick tells us. “You don’t erase history, you add to it. You should explain the good and the bad.”

As we continue down the hall, Losick points out artworks that professors have hung on the walls, including a mural of sea life along with a blue jellyfish with streamers hung up by Organismic and Evolutionary Biology professor Peter R. Girguis.

When we had visited Bio Labs the day before, Girguis had sat down with us for an impromptu interview. He’s skeptical that the third floor culture is particularly predisposed to scientific inquiry.

“I would say that the secret sauce of the third floor is that individuals have fortuitously ended up here by chance, and they have, through their own personality and dispositions, created labs or lab spaces that think outside the box,” Girguis said.

Girguis also thinks that Nobel prizes aren’t necessarily the best metric for scientific success and that the focus for scientists shouldn’t be on winning the Nobel Prize, but on excelling in whatever research they do. “It’s important to recognize that the Nobel does not adequately recognize excellence across all fields,” he says.

“If we want to call this a Nobel incubator, I hope what it does is it creates a sense that there is just so much we have to learn, and encourages scientists to be more audacious, to worry less about Nobel Prizes, ironically, to worry less about recognition, and do the work and push the envelope,” he adds.

Still, Losick hopes that by recording the history of these spaces, people will see the importance of “creating environments where people want to be committed to trying to answer challenging questions.”

“It’s a privilege to be here,” he adds.