News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

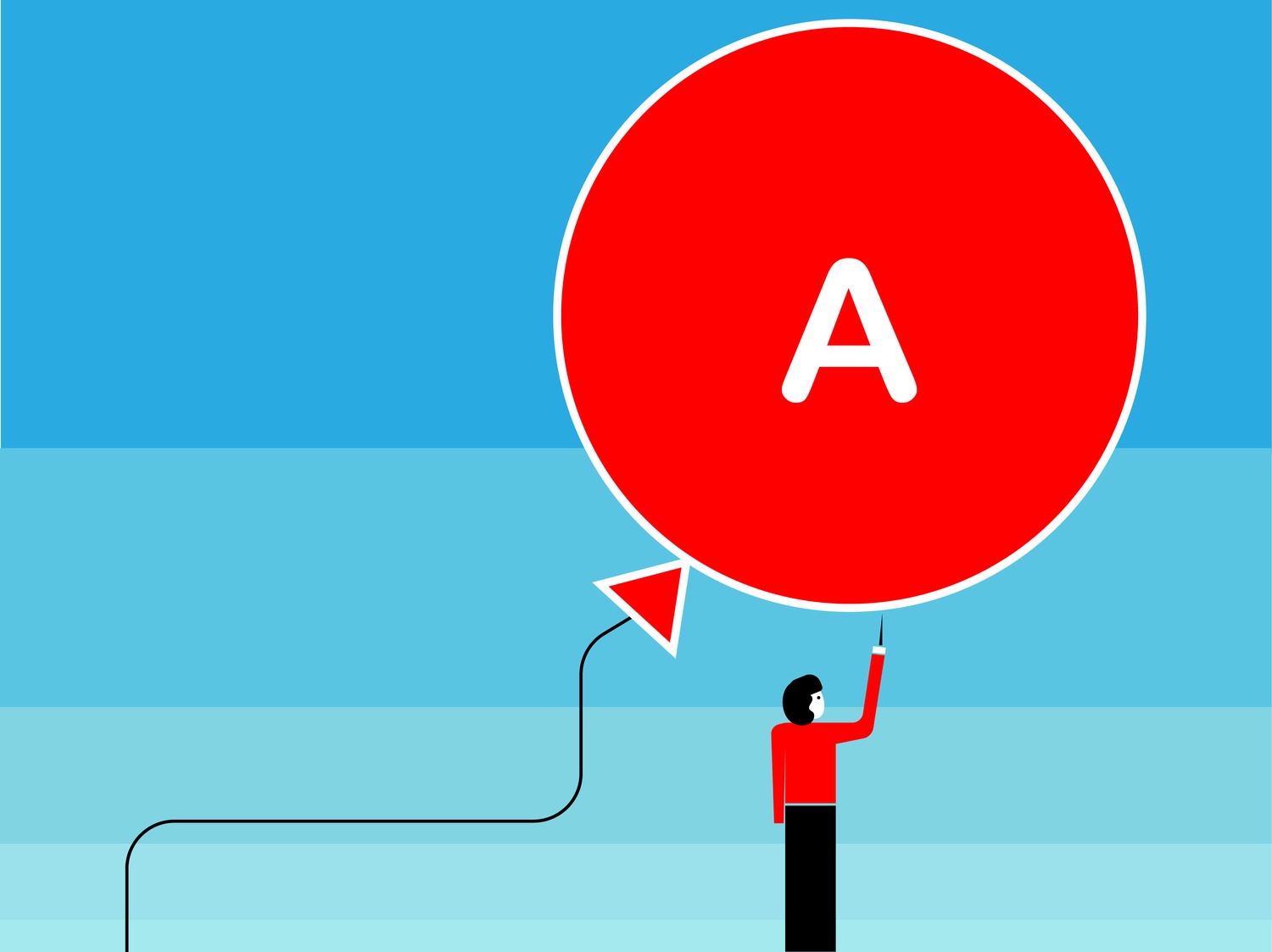

Harvard’s Too Easy. I Looked Into Literally Every Possible Way to Fix That.

You might have heard grades are going up.

Last year, a report presented to the Faculty of Arts and Sciences revealed the extent of Harvard’s staggering grade inflation. Nearly 80 percent of grades given to students at the College in the 2020–21 academic year were in the A-range.

I’m not here to argue the negative effects of grade inflation; many others have already done that persuasively. Instead, from conversations with friends, classmates, and colleagues on the Editorial Board, I’ve compiled every proposal I can find for solving grade inflation. This piece attempts to present — and evaluate — them all.

What are Grades, Anyway?

At their core, “grades” are just a set of buckets that cluster students of similar academic performance. Every university — and every class within a university — has a slightly different distribution of grades. A grading distribution might be spread out, with both As and Fs handed out liberally, or it could be condensed, with most students receiving Bs and Cs.

“Grade inflation” just means that the center of the grade distribution is slowly moving upwards, while “grade compression” refers to the distribution slowly becoming narrower. The two are linked: As grades rise, they push on the upper bound, causing them to compress closer and closer around an A.

In order to solve grade inflation and compression effectively, we must first figure out what the ideal grade distribution looks like, and to do that, we need to answer the question every student has muttered under their breath at some point: What’s the point of grading anyway?

As I see it, grades serve two purposes: to measure an individual student’s competency and to compare different students to each other. These metrics are related, but distinct — and there is, naturally, disagreement about which to prioritize.

A grading distribution where everyone receives an A signals a high degree of competency but fails to differentiate students. Conversely, a grading curve uniformly distributed among the different grading categories strongly distinguishes students, but if the class consists entirely of similarly capable scholars, it might inaccurately suggest significant differentiation between them.

A student’s individual grade sends a different signal depending on the overall university grading distribution. An A is much more valuable if the distribution is centered at a B-minus than if it is centered at an A-minus.

Curve It Like Beckham

The first set of grade inflation solutions involves the University setting a fixed grading distribution for each class. In its most extreme form, this approach could involve imposing quotas for each grading category. At minimum, the University could set an upper bound on the number of students who receive As.

There are several issues with this fixed distribution model, though.

First, it could lead to a situation where there are more deserving students than good grades to be given — if everyone in a Creative Writing seminar wrote excellent short stories, why should they not all receive As?

Second, limited fixed distributions might help inflation but not compression. A cap on As would likely shift the mean GPA downward, but it may not drastically change the spread of the distribution. Seventy-nine percent of grades are already in the A-range. It would be easy to imagine a fixed distribution merely shifting some of those As down to A-minuses.

Changing the Buckets

The University might instead consider changing the number of grade categories within the distribution. For example, why not switch from using 12 buckets — A through F — to just three or four?

Many professional schools across the country use an honors/pass/low pass/fail system, including both Harvard Law School and Harvard Business School.

But category changes don’t really solve the grade inflation problem — they just make it harder to detect. In some sense, letter grades are already functionally converging into honors/pass/fail — A, A-minus, or B-plus.

Furthermore, the fewer categories there are, the more we risk unfairly lumping students together. Should we really treat students who receive an 81 the same as ones who receive an 89?

In any event, Harvard seems to be moving in the opposite direction from pass/fail, with the College seemingly poised to eliminate the option for General Education courses.

Reducing the number of grading categories could be useful, however, during the first semester of college, in order to ease students into a new academic environment. At MIT, every first-semester student receives grades of either Pass or No Record, with a No Record not appearing on the student’s transcript.

Alternatively, Harvard could avoid excessively lumping students together by expanding the number of grading categories. Rather than converting percentages to letter grades, professors could assign students a qualitative final score out of 100, allowing them to better capture fine gradations between students.

Currently, a single percentage point can turn an A-minus into a B-plus — a difference that, in this day and age, can seem catastrophic. If Harvard adopted a 100-point scale, students would no longer have to stress over whether they will surpass the cutoff for each bucket.

And why stop at 100? Harvard could allow professors to choose their own upper bound. Why not 100,000?

Kidding. This would be impracticable and untenable — almost as much as a system that gives 79 percent of students A-range grades.

Full Transparency

Rather than changing the grading system itself, Harvard could clarify what a grade signals.

For example, the College could include on each student’s transcript the median grade for a course beside the student’s grade, providing employers and graduate schools a sense for the real achievement the latter represents.

After all, earning an A in The Ancient Greek Hero means something very different than earning one in Stat 110, and this policy could discourage students from taking the easiest classes by making it clear when they have done so.

The policy could be extended: Harvard could put the average GPA for a student’s concentration on their transcript to contextualize their performance more fully.

Make Harvard Harder

Finally, the University could simply make Harvard harder.

It’s the most natural way to deflate grades. If you want fewer students to receive As, then challenge us more. (We are Harvard students, after all.)

There are several ways to do this. First, and most intuitively, professors should grade more strictly. Many courses have leniency policies — including quiz and problem set drops, late days, and more — that increase the likelihood of receiving top grades. As a student, I can appreciate these rules for giving me wiggle room. But I also fail to see the benefit they bring to students’ learning.

The Faculty of Arts and Sciences could review course grading policies to see where these attempts at leniency have gotten out of hand. The Harvard College Program in General Education, for example, recently released guidelines recommending that students who miss class often, skip readings, or don’t complete assignments should not be given an A or A-minus.

One likely culprit for lenient grading is the Q Guide, which compiles student reviews of classes. Turns out, there is a direct correlation between expected grades and Q ratings. It isn’t hard to imagine that professors and teaching staff might be incentivized to make their courses easier or give higher grades in anticipation of better reviews.

Short of eliminating the Q Guide, Harvard should take this pressure off instructors by minimizing the importance of ratings when deciding teaching awards, promotions, and tenure.

Harvard could also simply make the course material itself more difficult by requiring all students to take certain rigorous classes like LPS A, Hum 10, Social Studies 10, or CS50.

Alternatively, the administration could change the number of credits each course yields. Because not all classes are equally difficult, maybe not every class should be worth the same on a transcript.

***

Despite widespread gem-hunting and fast-rising grades, I believe that most students come here to learn, not cut corners, and yet many end up doing just that. Maybe they do so out of fear. Maybe they don’t see the costs of taking the easy way out.

Regardless, they do so because they can. Ending grade inflation would free students from the disincentives that stand between them and a challenging, rewarding — and, yes, transformative — educational experience. And after all, Harvard students in particular need not fret about their grades — even the ugliest transcript has seven priceless Crimson letters at the top.

I see no reason not to explore every option to combat grade inflation. And like every Harvard student, I hope they’re adopted the year after I graduate.

Matthew R. Tobin ’27, a Crimson Editorial editor, is a double concentrator in Government and Economics in Winthrop House

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.