News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

Broken Tools, Missing Chairs: Harvard Undersupports Underrepresented Kids in STEM

Despite its status as a premier research institution, Harvard has for years struggled to adequately support underrepresented students interested in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

The disconnect between Harvard’s rhetoric and its actions is stark. While the University touts its commitment to diversifying STEM fields, I have experienced how these initiatives can fall short due to inadequate resources, disappointing eager young minds and failing to sufficiently lower the barriers between underrepresented groups and STEM careers.

For several years from 2017 to 2023, I served as a lab assistant for the Hinton Scholars Program at Harvard Medical School. The program has an admirable mission, bringing select Boston public school students taking Advanced Placement Biology to the Medical School’s campus to perform their work in Harvard’s lab facilities and participate in small-group tutoring led by medical and graduate students. In particular, the Hinton program strives to serve low-income and otherwise underrepresented students, and my students hailed from diverse backgrounds across the Boston area.

However, I have seen firsthand how the reality of the program falls far short of its goals.

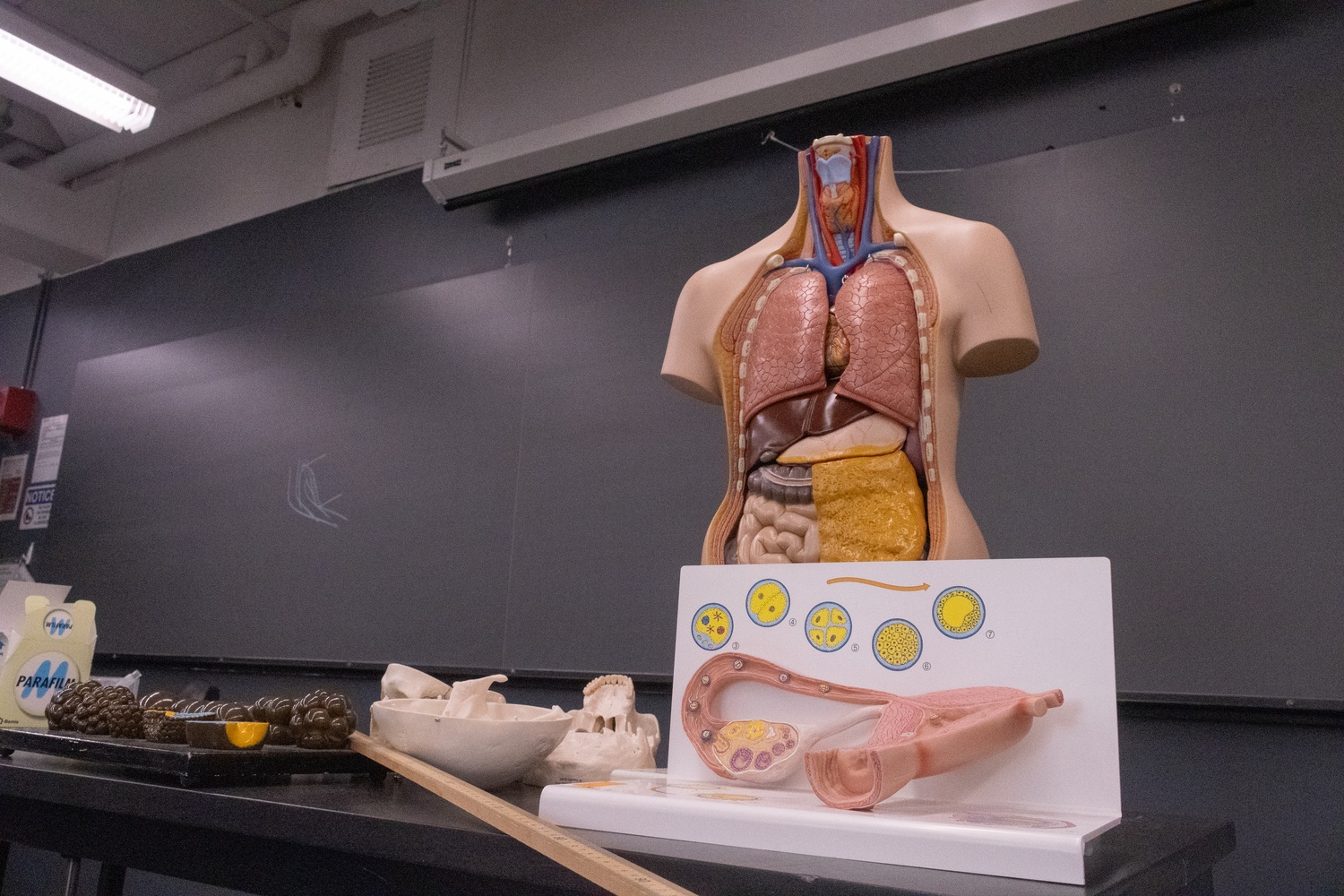

Of course, I have led engaged students in dozens of exciting experiments. We have analyzed their own DNA, examined microscopic pictures of plant leaves, and more. But the Medical School’s casual attitude toward the program and a lack of proper resources do a disservice to its participants.

Numerous pieces of equipment were missing or broken, slowing students’ progress on labs. In many cases, labs that are considered routine would fail because of broken sensors or failing batteries, leaving the students without any data. Frequently, there were too few chairs, so we’d have to waste time at the start of every class scavenging for more in nearby rooms. To boot, there was not enough benchtop space for the students to comfortably perform the labs. When a student asked me at one point why there were not enough chairs in our classroom at Harvard, I felt a profound sense of shame.

For more than two years, I worked with the Office for Diversity Inclusion and Community Partnership and the Campus Planning Office to address these issues. I crafted a proposal for renovating the space, which DICP forwarded to the Campus Planning office. But to no avail: I was told after several months that any improvements would have to wait. No meaningful short-term solutions were proposed, and a DICP official made clear to me that my input was no longer welcome.

The Hinton Program aims to engage with student groups that have historically been underrepresented in STEM, but broken equipment and cramped lab space only exacerbate feelings of exclusion. By delivering subpar resources for these high school students, Harvard replicates the very inequity the program hopes to address.

Perhaps I was naive to think that Harvard would be enthusiastic about improving programs meant to serve its community. My efforts have certainly been met with astounding apathy. Is this the best that Harvard Medical School — a leading institution devoted to health, teaching, and community service — can do?

The Hinton Scholars Program was named after William Augustus Hinton, Class of 1905, an incredible pioneering physician and Harvard University’s first Black professor. The irony of the program’s namesake is not lost on those familiar with Harvard’s history — only after 30 years of service to HMS in a variety of teaching roles, on the eve of his retirement, was Hinton made a full professor.

Harvard must do better. The program’s aims are noble, but it does not provide sufficient support for these students in its own community. The University must invest the time, effort, and resources necessary to deliver on its promise and provide these talented young scientists with the opportunity they deserve.

Alexandra Panov received her PhD in Biological and Biomedical Sciences from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.