News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

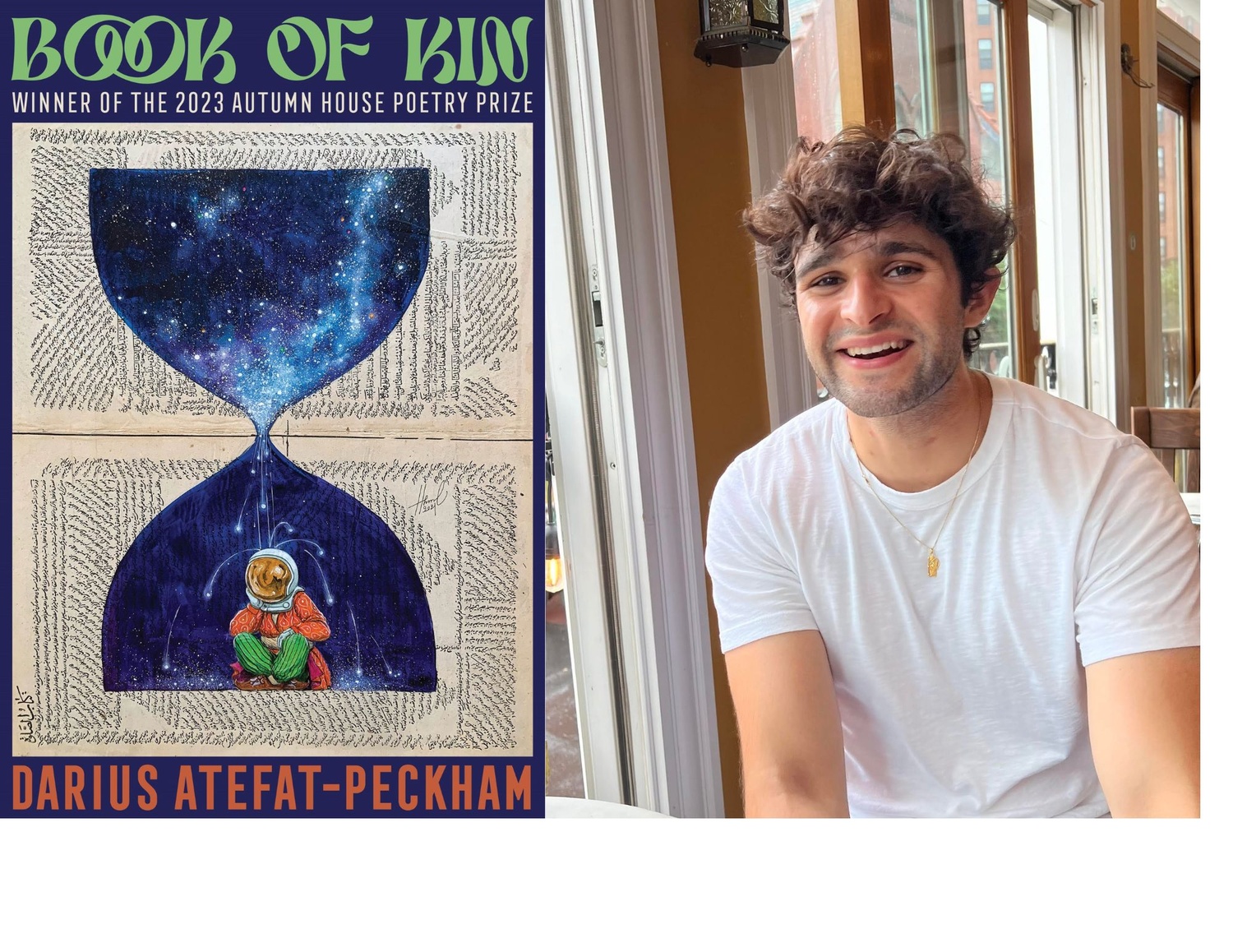

Harvard Authors Profile: Darius Atefat-Peckham ’23 on Poetry as Sincerity and the Bridging of Identities

“Just to preface, I’m really long winded. So, good luck to you, Caroline,” said Darius Atefat-Peckham ’23, Iranian American poet and author of “How Many Love Poems” and his latest collection, “Book of Kin.”Atefat-Peckham is a fan of long conversations. He is a writer who has a lot to say and, luckily, an enthusiasm to say it.

In an interview with The Crimson, Atefat-Peckham shared his profound insights on life, love, and the ultimate power of artistic endeavor.

Atefat-Peckham may have a lot to say, but he also fervently believes in the importance of listening, a theme that resonates deeply in his work.

“You know, we think about writing as this torrential kind of self-expressive mode. But then poetry has so much white space, so much silence in it,” Atefat-Peckham said.

His mentorship under Tracy K. Smith played a pivotal role in shaping this perspective. Professor Smith, who served as his creative thesis advisor at Harvard College, praised his generosity in his poems but also challenged him to cultivate a relationship with silence — a concept he initially struggled with.

Atefat-Peckham emphasized how Professor Smith pushed him to “work on his relationship with silence,” humorously recounting the conversation.

“I talked at her for 40 minutes and I was like, ‘what do you mean?’” Atefat-Peckham said.

Professor Smith also consistently pushed him to explore the broader possibilities of poetry, asking critical questions about what it means to speak for a community.

For Atefat-Peckham, these lessons intertwined with his exploration of identity. Poetry became a way to navigate and explore the complexities of his “bridged identity,” a term he uses to describe his hyphenated Iranian American self. Central to this exploration is his relationship with the Persian language. He reflects on the levels of language fluency and questions what it truly means to “speak well” in Persian. Is fluency merely the ability to express emotions like “I love you” and “I miss you” or does it encompass the capacity to articulate oneself in more nuanced ways?

For Atefat-Peckham, language is not just deeply tied to place, it is also eternally connected to love. In “Book of Kin,” Atefat-Peckham embraces the Persian that he knows and lives in. He accepts that his Persian can exist “broken” and this acceptance becomes a crucial element of his poetic expression.

Atefat-Peckham expressed how language, too, informs the physical form of his work. Because Farsi is read from right to left, Atefat-Peckham has become more conscious of both the beginning and end of a poetic line. This awareness mirrors his broader exploration of identity, with each line serving as a bridge between different facets of his experience — American and Iranian, English and Persian, past and present. In this way, his poems embody the fluidity of his identity.

“For me, poetry is confronting mystery. When I go to poetry, I am seeking a deeper connection with a beloved place, a heritage I don't know,” Atefat-Peckham said.

The lines are more than just segments of text, they are symbolic journeys across the terrain of his cultural and linguistic landscape.

“Poetry became an alternate form of travel to a place I couldn't go physically,” Atefat-Peckham said.

This place for Atefat-Peckham is Iran, the place of heritage for his mother, who passed away in a car accident along with his older brother when Afefat-Peckham was young. For him, poetry is a way to honor both his family and his heritage, and explore the complexities of doing both at once. The act of writing, to him, is also an act of memorialization. Atefat-Peckham envisions how “absence becomes a kind of presence” and sees loss and love as existing simultaneously in his work. He believes that “longing is an expression of love.” The act of “reaching out and addressing a beloved” is another power of poetry.

While writing “Book of Kin”, Atefat-Peckham witnessed how similar love poems and elegies truly are. Atefat-Peckham shared how this perspective informed his appreciation and use of the ghazal, a traditional Persian poetic form where each couplet is autonomous and “has its own universe within it.” In this form, one can seamlessly move from addressing a romantic beloved in one couplet to mourning a lost loved one in the next, without altering the nature of the address.

“Dying is just another kind of existence,” Atefat-Peckham said.

Atefat-Peckham believes that “great poetry is great sincerity.” For him, poetry is a unique vehicle to access this sincerity because it allows for the exploration of the subconscious with a kind of creative abandon. This poetic freedom reflects the authenticity of lived experiences.

“One of my mentors used to say, live first, write second,” Atefat-Peckham said.

He practices this advice in his words on and off the page. Atefat-Peckham speaks about his journey as a poet and a person with grace, gratitude, and love. He exemplifies the power of poetry itself — to find wonder, to inspire change, to provoke thought, and to nurture compassion in an increasingly complex world.

—Staff writer Caroline J. Rubin can be reached at caroline.rubin@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.