‘The Architect of the Whole Plan’: Harvard Law Graduate Ken Chesebro’s Path to Jan. 6

On Jan. 6, Kenneth J. Chesebro was seen outside the Capitol wearing a red “Trump 2020” hat as rioters amassed around the building, according to CNN. But two decades earlier, in Bush v. Gore, Chesebro worked extensively under liberal legal scholar Laurence H. Tribe to craft a legal justification to recount votes in Florida. By Toby R. Ma

By Toby R. Ma

‘The Architect of the Whole Plan’: Harvard Law Graduate Ken Chesebro’s Path to Jan. 6

On Jan. 6, Kenneth J. Chesebro was seen outside the Capitol wearing a red “Trump 2020” hat as rioters amassed around the building, according to CNN. But two decades earlier, in Bush v. Gore, Chesebro worked extensively under liberal legal scholar Laurence H. Tribe to craft a legal justification to recount votes in Florida.In 2000, long before Kenneth J. Chesebro entered the limelight as “Co-Conspirator 5” in the Justice Department’s indictment of Donald J. Trump, he worked under the tutelage of Harvard Law School professor Laurence H. Tribe for another high-profile presidential candidate: former Vice President Al Gore ’69.

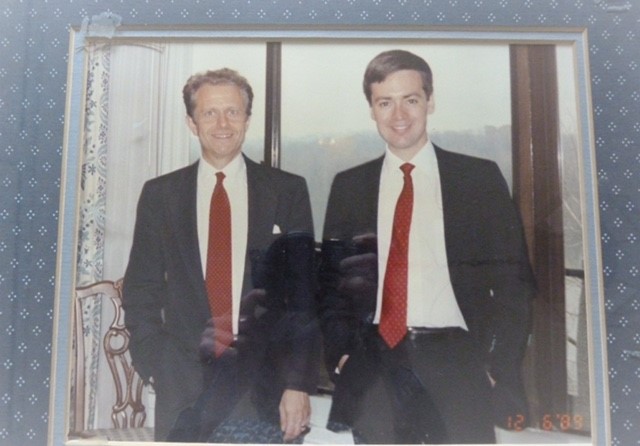

Chesebro, who began working with Tribe as a student in the Law School, continued as one of his research assistants well after graduating from HLS in 1986. Two decades after he worked with the liberal legal scholar — on cases Tribe described as “mostly for the victims of corporate greed and of government abuse” — Chesebro joined Trump’s legal team.

Six days after the 2020 presidential election, Chesebro was contacted by Trump’s legal team, and soon after, he became a central player in the campaign’s efforts to overturn Joe Biden’s victory in the 2020 election. He outlined a plan to appoint false electors in states Biden won with the goal of using then-Vice President Mike Pence’s ceremonial role overseeing the electoral vote count on Jan. 6, 2021 to instead declare Trump the winner.

In the Aug. 1 federal indictment of Trump, special counsel Jack Smith described Chesebro — without naming him, instead referring to him as Co-Conspirator 5 — as “an attorney who assisted in devising and attempting to implement a plan to submit fraudulent slates of presidential electors to obstruct the certification proceeding.”

On Jan. 6, Chesebro was seen outside the Capitol wearing a red “Trump 2020” hat as rioters amassed around the building, according to CNN — though he did not appear to illegally enter or engage in violence himself.

Two decades earlier, in Bush v. Gore, Chesebro worked extensively under Tribe to craft a legal justification to recount votes in Florida. He later cited his former mentor in a series of confidential memos for the Trump campaign that conveyed his plan to use an “alternate slate of electors” to stop the Biden campaign from reaching 270 electoral votes.

Tribe has since publicly referred to Chesebro’s citation of his work as a “gross misrepresentation” of his scholarship.

“From the very first memo, he was twisting the research and making it clear that there were no limits of honesty or principle that would prevent him from basically scheming to overturn the election,” Tribe said.

“It’s not as though you can make a legal argument for having a fake elector,” he added.

Chesebro and his attorney did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Chesebro currently faces seven criminal charges in Georgia relating to the effort to overturn the election along with Trump and 17 other co-defendants. He has since pleaded not guilty on all counts and requested his trial be expedited and severed from proceedings for the other defendants.

On Wednesday, Georgia Judge Scott McAfee denied Chesebro’s motion to sever his case, ruling that he will be tried alongside co-defendant Sidney K. Powell, who also requested a speedy trial. The court is still weighing whether all 19 defendants must be tried together.

Chesebro’s trial alongside Powell is scheduled to start Oct. 23. It will likely be televised.

‘A Yes Man’

When Chesebro arrived at the Law School in 1983, Tribe — just 41 years old at the time — had already argued before the United States Supreme Court six times and had attained tenure at age 30.

A seat in one of Tribe’s classes, let alone on his research team, was highly coveted.

“Everyone wanted to take his class,” said Jack H. Cleland, a 1987 Harvard Law School graduate and member of the Harvard Law Review alongside Chesebro.

For his part, Chesebro — nicknamed “the Cheese” both in reference to his Wisconsin roots and his surname — was described by many of his classmates as an extremely hard worker. When Chesebro offered to be one of Tribe’s research assistants after taking his constitutional law class, Tribe agreed and said Chesebro “could be counted on” for thorough legal research.

Working for Tribe, Chesebro joined a high-powered group of law students, including Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan and former President Barack Obama, in which Tribe said Chesebro “held his own in terms of intellectual acumen and thoroughness.”

Still, “it was pretty clear that [Chesebro] was less mature than some of the others” and “didn’t have the same kind of judgment,” Tribe said.

Unlike the other apprentices, Chesebro spent time on the Law School’s campus and worked for Tribe long after he graduated. Tribe would go on to argue 29 more cases before the highest court, of which at least one — Bush v. Gore — intimately involved Chesebro.

Bush v. Gore arose out of the 2000 presidential election. Gore won the popular vote, but the electoral college count came down to Florida, where the margin of victory for George W. Bush was less than 0.5 percent. After a machine recount, Bush led by just 327 votes.

The Florida Supreme Court ordered an immediate manual recount in four counties, but the Bush campaign petitioned the Supreme Court to prevent it. Tribe, assisted by Chesebro among others, served as lead counsel on Gore’s legal team in the wake of the contested election.

In a 7-2 decision, the Court ruled that the recount violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, confirming Bush’s victory.

Importantly, the Court also ruled that a recount could not take place because the “safe harbor” deadline — the final cutoff for resolving presidential elector disputes — had passed.

After the Supreme Court ruled in Bush’s favor in December 2000, Chesebro continued to work with Tribe on a range of cases that were “mostly on the liberal side of things,” according to Tribe.

“I think I took a number of things for granted because the cases on which he worked so enthusiastically were cases that I felt committed to both legally and morally. I somewhat assumed that he was on the same page,” Tribe said.

“He was always, if anything, too much of a kind of a yes man,” Tribe added.

During their last conversation, Chesebro tried to convince Tribe to invest in Bitcoin after its launch in 2009.

“When I told him I wasn’t interested, I think that was the last I ever heard from him,” Tribe said.

‘Guilty of Being Just a Committed Lawyer’

The same man who was recently indicted for the fake electors scheme to keep Trump, a Republican, in the White House appeared for most of his career — at least, outwardly — to be a Democrat.

In addition to working on mostly liberal legal causes with Tribe, Chesebro was a registered Democrat until 2016 and appeared committed to the party through his political contributions, donating to the likes of former President Bill Clinton and former Secretary of State John Kerry early in his career. Chesebro also expressed enthusiastic support for Obama when he was a political candidate.

Law School classmate Jeffrey R. Toobin ’82, another of Tribe’s former research assistants, said Chesebro aimed to “push the envelope” by making “creative, aggressive legal arguments.”

Toobin said he believes Chesebro applied these tactics in his recent work for Trump.

“It’s just that he did it here for a politically contradictory goal to all his goals for the rest of his life,” said Toobin, a former Crimson editor. “His views, at least according to the state of Georgia, were not just aggressive, they were criminal.”

Chesebro dropped his affiliation with the Democratic Party to become an independent voter in 2016, marking the start of his public transformation to a staunch Republican. He began working with former judge and Trump campaign attorney Jim R. Troupis and began donating to the party’s candidates — including Trump.

The timing coincided with both his divorce from his wife of more than 20 years and communication with Tribe boasting a several million dollar profit from investing in Bitcoin through digital asset management firm Grayscale Investments.

Marc S. Mayerson, one of Chesebro’s first-year section mates at Harvard Law School, disagreed with the characterization of Chesebro as a liberal in his earlier years.

“Working with Tribe who was super famous and everything is sensible, but I didn’t think it really reflected his political commitments, per se,” Mayerson said.

“Ken was guilty of being just a committed lawyer and being lost in the technical interests of the question,” he added. “It’s not uncommon, in my experience as a lawyer for 35 years, that people sometimes lose sight of true north — meaning, in my vocabulary, some sort of moral direction.”

Tribe described Chesebro as a people pleaser and said he was “sure” that was connected to “how he glommed on to the Trump cult when he did.”

‘An Alternate Slate of Electors’

On Nov. 18, 2020, Chesebro sent a confidential memo to Troupis, a fellow Trump attorney, titled “The Real Deadline for Settling a State’s Electoral Votes” — an early document detailing key aspects of the fake electors scheme.

In the memo, Chesebro argued that the true deadline for courts to settle electoral vote disputes in the 2020 election was not the Dec. 8 “safe harbor” deadline — by which states must choose electors and resolve disputes over their choices — or the Dec. 14 voting deadline, but instead Jan. 6 — when Congress meets to count the votes.

The question of elector deadlines was one that Chesebro worked on while advising Gore and his campaign under Tribe and in at least two of his memos — including the Nov. 18 memo — Chesebro cited Tribe directly.

Tribe responded to the memo in a piece written in online blog Just Security, calling Chesebro’s citation of his work as a “misuse of what I had written.”

“Under Florida law, there was really no requirement to get the counting done until the very last minute — until January 6 of the next year in which the new president would be inaugurated,” Tribe said in an interview.

“He took that and more or less deleted the parts of the sentence that made it all about Florida and pretended that I had somehow reached the conclusion that you could disregard deadlines, including the deadlines set in the Electoral Count Act,” Tribe added. “That, I had never remotely thought.”

HLS professor emeritus Alan M. Dershowitz — who previously publicly feuded with Tribe over matters concerning Trump — disagreed with the characterization of Tribe’s work as having a completely different meaning from Chesebro’s argument.

“No two cases are ever the same. No two elections are ever the same. No two protests about elections are ever the same,” Dershowitz said. “But there is a striking similarity between some of the arguments made by Laurence Tribe on behalf of Al Gore and some of the arguments made by Chesebro and some of the other defendants in the Trump case.”

“There are differences, too, but there are similarities,” he added.

In a second public memo, from Dec. 6, 2020, Chesebro wrote to Troupis with the subject line “Important that All Trump-Pence Electors Vote on December 14.” Chesebro wrote the memo as a follow-up to his Nov. 18 memo, writing about the possibility of enacting an “alternate slate of electors” in support of the Trump campaign.

Chesebro wrote in this document that he was “not necessarily advising this course of action” but that “it is important that the alternate slates of electors meet and vote on December 14 if we are to create a scenario under which Biden can be prevented from reaching 270 electoral votes.”

He also wrote that prior to Dec. 14, “there should be messaging that presents this as a routine measure that it is necessary to ensure that in the event the courts (or state legislatures) were to later conclude that Trump actually won the state, the correct electoral slate can be counted in Congress in January.”

In the Dec. 6 memo, Chesebro also referenced Tribe’s Harvard Law Review article that he cited in his Nov. 18 memo — saying that Tribe “has likewise noted that the only real deadline for a State’s electoral votes to be finalized is ‘before Congress starts to count the votes on Jan. 6.’”

He also argued that Pence, in his role overseeing the electoral count, would have the option to “both open and count the votes and that anything in the Electoral Count Act to the contrary is unconstitutional” — in essence, allowing Pence to count the Trump electors and discard the lawful Biden electors from the contested states.

In a third memo, from Dec. 9, 2020, Chesebro wrote to Troupis about instructions for creating an alternate slate of electors in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. The memo was titled “Statutory Requirements for December 14 Electoral Votes.”

In the document, Chesebro details requirements in federal and state law for the alternate electors, at times raising doubts about the feasibility of the plan.

A Speedy Trial

Chesebro is one of six unnamed co-conspirators in the federal Jan. 6 indictment — with the possibility of future charges in that case — and one of 19 defendants in the Georgia indictment brought by Fulton County District Attorney Fani T. Willis.

With their requests for a speedy trial approved, Chesebro and Powell will almost certainly be the first of Trump’s co-defendants to face a jury.

According to Toobin, Chesebro’s former classmate and a former CNN legal analyst, “the central issue” in Chesebro’s case in Georgia is “the line between aggressive lawyering and instructing clients to break the law.”

“We don’t want to criminalize aggressive lawyering but at the same time, we don’t want to give lawyers immunity from conspiracy charges just because they’re lawyers,” Toobin said.

According to Dershowitz, the choice to prosecute Trump, Chesebro, and their co-defendants in the Georgia case was an example of “a double standard” and that in both the Gore and Trump cases, there should not have been criminal prosecution.

Dershowitz added that while a lawyer cannot knowingly advise a client to break the law, “a lawyer can advise a client to take actions which are later determined to be in violation of the law as long as he had a good faith and reasonable belief that he was acting within the law.”

“You have to judge it at the time he made the recommendations and you have to judge it through the prism of his own reasonable beliefs,” Dershowitz said.

In both the state and federal cases, there is widespread speculation that one or more of Trump’s alleged accomplices may agree to cooperate in exchange for a plea deal.

The possibility of “flipping” a co-conspirator could explain why Smith, the special counsel, chose not to name Chesebro and the five other co-conspirators referenced in the indictment — though any could still face federal charges.

“Prosecutors live to flip co-defendants,” Dershowitz said. “That’s why they named them as unindicted co-conspirators.”

Dershowitz, a former member of Trump’s legal team during his first impeachment trial in 2020, said he predicts at least one of the six co-conspirators will flip.

According to the indictment, Chesebro and former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani — one of the former president’s longtime personal lawyers who is referenced by Smith as “Co-Conspirator 1” — discussed the use of fraudulent electors at length. The indictment alleges Giuliani instructed Chesebro to distribute his memos to state governments.

Tribe speculated that if Chesebro had any useful information for prosecutors, it would be in relation to Guliani or ex-Trump attorney John C. Eastman, who is referenced in the indictment as “Co-Conspirator 2.”

Harvey A. Silverglate, Eastman’s co-counsel and a 1967 graduate of the Law School, said in any case with multiple defendants, there is “always a fear” that other co-conspirators will make a deal.

“They can make up things that Eastman said that he didn’t really say. It’s not that hard,” said Silverglate, who is a member of the Dunster House Senior Common Room and staged a longshot Board of Overseers campaign earlier this year.

For his part, Silverglate said Eastman will not make a deal with prosecutors and hopes his case will get severed “so that we can try the case months from now rather than years from now.”

Unlike Chesebro, Eastman has not filed a request to have his case be tried separately.

At least in the Georgia case, Tribe said Chesebro’s actions so far do not indicate any intention to flip; as Tribe observed, “he certainly hasn’t been cooperative with Fani Willis so far.”

Tribe said that even if Chesebro wanted to take a deal and provide information to Willis, he doubted Chesebro would have “anything terribly valuable to say that would make him worth accepting a guilty plea from.”

“He’s so much the architect of the whole plan that I think it’s very hard to imagine him getting off without a multi-year sentence,” he added.

Tribe added that he was shocked when he first learned of the nature of Chesebro’s involvement with the Trump campaign.

“Part of me felt sorry for him. Part of me felt angry that he would betray the country and the Constitution in that way. Part of me felt it was such a terrible waste,” Tribe said. “He had a good mind, and he was putting it to use for obviously evil purposes.”

—Staff writer Cam E. Kettles can be reached at cam.kettles@thecrimson.com. Follow her on X @cam_kettles.

—Staff writer Neil H. Shah can be reached at neil.shah@thecrimson.com. Follow him on X @neilhshah15.