News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

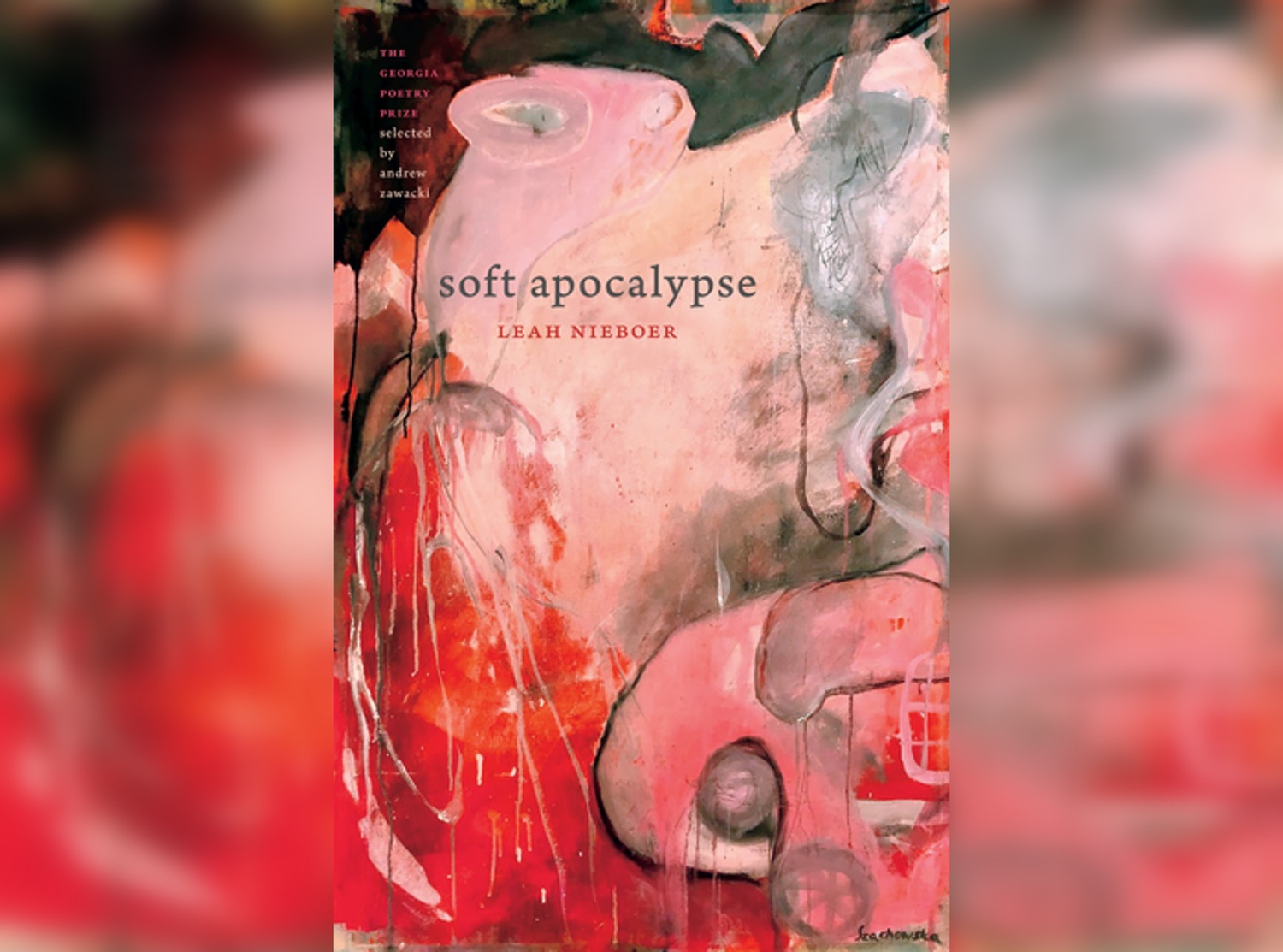

‘Soft Apocalypse’ Review: Love Conquers All in Leah Nieboer’s Neon Futuristic Dream Stream

4 Stars

In her new poetry collection “Soft Apocalypse,” which won the 2021 Georgia Poetry Prize, poet Leah Nieboer creates an eerie, neon-backlit, postmodern American universe, populated by characters who find solace and support in each other amidst a setting of pockmarked, post-industrial ruin. Despite verse that is at times agonizingly sparse and unnecessarily twisted, the collection embodies a distinct, cohesive sense of hope and companionship that ties together the vivid, bright pink “beloveds” — Nieboer’s characters — in her poems. As the reader walks delicately through this world, pirouetting through dioramas and revolving nights, their sense of time and the physical spaces around them are slowly reoriented.

Stepping through the revolving door of the opening poem “ONLY IN MY NIGHTS DID THE WORLD SLOWLY REVOLVE,” the speaker meets an “implausible cosmonaut / in her heart-shaped sunglasses / in her slick ruby suit.” This cosmonaut conjures up images of Lorraine Broughton, the titular undercover spy from “Atomic Blonde”: slick and sexy, bringing posh into the arena of destruction.

The collection is thus littered with these fields of destruction as Nieober convincingly paints the dying vestiges of the world as a production machine whose goal is to strip away our deep-rooted connections with each other and with humanity at large. In “FLASH PROCESSING OF A PRIVATE YEAR,” this production machine comes at odds with the speaker’s health. When the speaker goes to the pharmacy dispensary, a central location in Nieboer’s poems, the clinical lists of medical terms and diagnoses in front of the “fissure window” mimic the “uneasy cosmology” of navigating illness in daily life when the structures of work and capital actively oppose rest and remedy.

The speaker’s hopelessness in this poem motivates her to take “a bright pink pill” as the “kiss of an answer,” further perpetuating her illness and desperation. Form marries content as the speaker describes how, after taking the pill, she sees a “prayer” as a “glittering record inside of what an unfeeling sentence.” Even hopeful ideas of “prayer” here are co-opted by the uninspired machinations of the hard-edged world through bounds of structure, diction, and form — the structures through which the speaker views and experiences the world.

In the depths of the coarse, roughened remnants of “what had once been a great city,” however, the speaker finds a “soft underside.” In “MINOR EVENTS 2,” they realize that one can “pretend” to be a cosmonaut, a “private explorer” swimming to the “edge of a dazzling pool.” In “THINGS HAVE GONE BACK TO BEING WHAT THEY WERE,” Nieboer’s language invites a camaraderie between the gashes in nature and the tenderness of human hands: “I stood on a roof half-dressed watching a / jet wake stretch itself into the most insane blue you’ll ever / in sunlight see.” Under the speaker’s loving gaze, sidewalks nurse cracks and dresses stitch together their tears.

Some of the sparse verse, quick enjambments, and inconsistent diction in the collection, though, prevents some poems’ conclusions from feeling satisfactory, leaving the reader afloat in a sea of free-flowing ideas and images. In “Washed Up Ultraviolet Morning,” the italicized “giving thought to distances” and “we could try a different location” seem unmoored from the lines before or after, creating a decentralized, sporadic feeling to the reading process that feels unintentional. In the same poem, the speaker shares a dream of “an edible flower / its round leaves / a buttery orange / expression of // nasturtium.” The enjambments here seem breathless, diluted rather than crystallized. In “Space Without Map,”

“someone’s forgotten something

important –

the hour bows down

a body bends to the curve

exceeding the function

the sound of

the moment slips”

The line never finishes — the “function” is never verbalized or explained in full. Instead, the poem stutters: “the sound of / the moment slips.” The incompleteness of the line creates a slightly frustrated reading process. Nieboer’s use of indented and free form alongside italics also dilutes the poem and distracts the reader further.

Despite some confusing technical and syntactical choices, Nieboer nevertheless imbues the collection with a vivid celebration of hope and friendship. Love for the body, the self, and the humans that share this earth are equally important to celebrate in Nieboer’s poems. “It’s important to me / to memorize one’s own / temporary address,” she writes in “SPACE WITHOUT MAP,” referring to the body itself. In this poem, the speaker, and Nieboer herself, celebrates our bodies as vessels that have carried us through countless “soft apocalypses” and more. The book ends with the speaker sitting with “gorgeous people” in the back of a stretch limousine, narrating, “we were here giving each other / explicit reasons / to go on.” The speaker clearly and forwardly celebrates the individuals that make life worth living. The ending is a tribute to the project of the entire poetry collection: an ode to friendship and companionship despite the aberrations of the glowing anemic world.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.