Bird Brilliance: Exploring Harvard’s Ornithology Collection

Lined with endless rows of white cabinets, Harvard’s Ornithology Collection is imposing — even mausoleum-like — upon first glance; it’s only after opening the drawers that the true colors of the collection are revealed. Since it was founded in 1859, it has become the fifth-largest ornithological collection on Earth, boasting around 400,000 specimens and 8,300 species — over 85 percent of all known bird species.

Jeremiah Trimble, a curatorial associate and the manager of the collection, helps coordinate the work of anyone seeking to use the collection. “The specimens are used in all kinds of ways. They’re used in anything from artists creating field guides,” he says, “to taking feather samples to look at isotopes to understand diet or environmental contaminants.”

Each specimen affords valuable insight into the history and future of birds. “The specimens provide a snapshot in time about a species and where it occurred,” Trimble says. “People can use them to look at how genetics have changed within a species over time.”

The collection houses a bee hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae), which is hardly larger than a penny. Weighing in at under two grams, the bee hummingbird is the smallest species of bird on earth and can only be found in Cuba.

Another bird in the collection is the rhinoceros hornbill (Buceros rhinoceros). Native to the forests of Malaysia, Java, Sumatra, and Borneo, this species can be easily identified by its distinctive horn, also known as a casque, used to attract mates and increase the intensity of their calls. However, the casque has also made the bird a target for poachers.

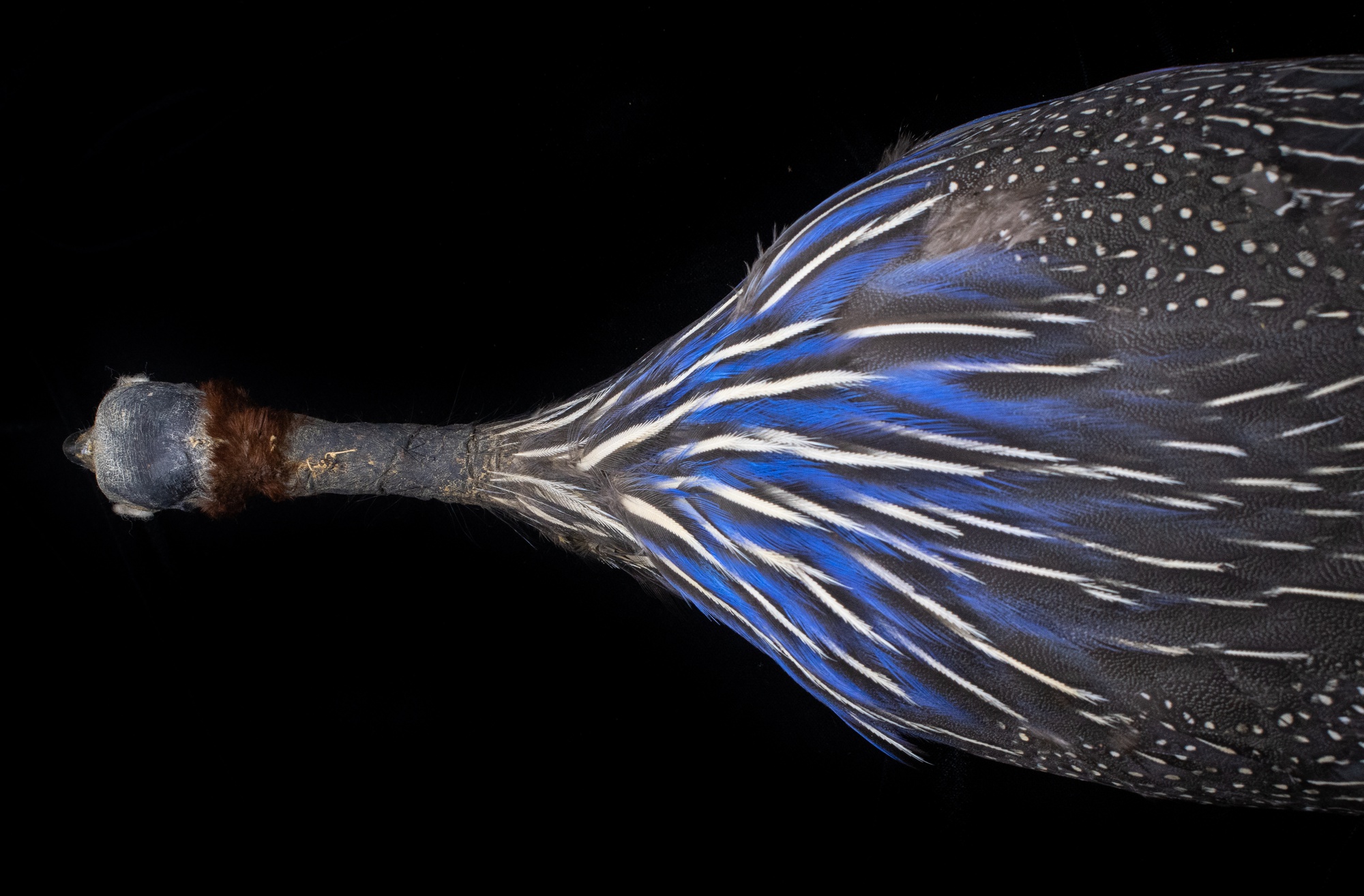

The vulturine guineafowl (Acryllium vulturinum) may not have an impressive casque like the hornbill, but it makes up for this with its incredible feathers. Decorated with countless white speckles and an electric blue collar, this ground-dwelling species is a standout in the savannas of northeastern Africa. Social by nature, the vulturine guineafowl can be observed in small- to medium-sized flocks as it searches the parched scrub for invertebrates and seeds.

Driven by sexual selection and geographic isolation, the king birds-of-paradise (Cicinnurus regius) are some of the flashiest birds in the sky. Come mating season, the male birds sway side to side, holding up their iridescent disk-shaped tail feathers to seduce females.

Similarly, the tail feathers of the Wilson’s bird-of-paradise (Cicinnurus respublica) have evolved into delicate spirals in order to help attract mates. These bright plumes help cut through the darkness of the shadowy forest floor where these birds reside.

The collection features one of the few remaining specimens of the now-extinct black mamo (Drepanis funerea). These birds used to live on the island of Molokai; however, invasive species destroyed the black mamo’s natural habitat and preyed upon their young. The last black mamo was collected in 1907. Though Harvard’s Ornithology Collection may be filled with beautiful displays, it also serves as a poignant reminder of the way humans have impacted the environment and those living in it.