News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

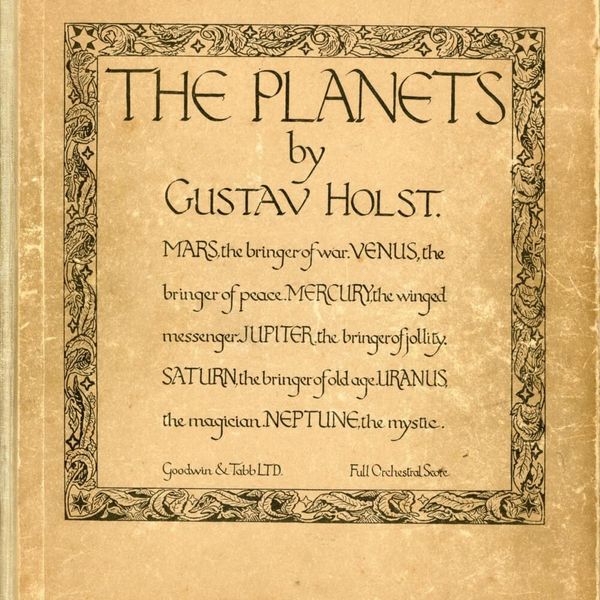

‘The Planets’ Retrospective: Holst’s Spectacular, Forward-Looking Journey Through Music, Space, and the Mind

“The enormity of the universe revealed by science cannot readily be grasped by the human brain, but the music of ‘The Planets’ enables the mind to acquire some comprehension of the vastness of space where rational understanding fails,” English composer and music teacher Gustav Holst said of “The Planets,” his 1916 seven-movement orchestral suite.

“The Planets,” Op. 32 holds surpassing cultural significance, not only for its musical excellence and entertainment value, but also due to its ingenuity, foresight, and timelessness.

Holst (1874-1934) was “feeling rather tired of life” in the early 1910s, according to his friend Clifford Bax. He lived in foggy air that harmed his breathing; his ode “The Cloud Messenger” was poorly received, like his other failed pieces; and he was exhausted by his fast-paced life. However, by 1913, Holst found new, refreshing peace: He moved to a new house, he was given a sound-proof music room at St. Paul’s Girls’ School, where he worked as music director, and Bax introduced him to astrology and horoscopes, which Holst referred to as his “pet vice.”

Inspired by astrology, Holst began composing “The Planets” in 1914 in his tranquil sound-proof room. First met with mixed reception, the orchestral suite found international success in the years following World War I. Each movement is named after a different planet in the solar system, but Holst clarified that his work was neither influenced by astronomy nor mythology. “The Planets” was inspired by astrology and developed through musicality and an objective to portray the planets as characters with distinct moods — moods according to horoscopes, as well as Holst’s personal moods.

“The Planets” evokes wonder; it is dynamic, captivating, and otherworldly. Both grandiose and sensitive, the suite includes moments of drama and moments of serenity, conveying planetary mystery and Holst’s aim to depict a variety of emotions. In every moment, invigorating energy allows the music to fill expansive, seemingly endless space — embodying the theme of the suite.

Holst’s suite stands out from the music of its time due to its innovative style. “The Planets” takes advantage of the Modern era’s structural flexibility and rule-breaking. However, it also embraces the Postmodern era through contradictions, rejection of binary oppositions, and incorporation of additional cultures, drawing on ancient Eastern philosophies and Hindu spiritualism. The Postmodern era did not truly begin until decades later, making “The Planets” ahead of its time. The suite’s power to incite audiences’ visual imagination is reminiscent of a soundtrack to a videogame or a science fiction film, and its interdisciplinary connection to astronomy (despite Holst’s claimed lack of scientific influence), make the suite suitable for more contemporary periods.

“The Planets” remarkably captures the nature of the real planets — which is surprising, considering the deficiency of astronomical information in 1914.

The most popular movements of “The Planets” are “Mars: The Bringer of War” and “Jupiter: The Bringer of Jollity.” The fierceness of “Mars,” its allegro tempo, and its striking brass and timpani reflect the planet’s dry, rocky, and red-colored physical features, its goal to disdain war relates to the planet’s proximity to Earth, and its aggressiveness anticipates the contemporary desire to explore the planet. “Jupiter” is grand, regal, and imposing, with an exuberant and broad melody, accurate to the planet’s massive size — but its most compelling elements are its unresolved final cadence, suggestive of planet’s perplexing, high-pressure anticyclone, The Great Red Spot, and its buoyancy, suggestive of the planet’s beautiful, windy colorful stripes and swirls.

The other movements, including “Venus: the Bringer of Peace,” “Saturn: the Bringer of Old Age,” and “Neptune: the Mystic” also relate to their planetary counterparts. The flutes and harps of “Venus” illustrate the planet’s thick atmosphere and its comforting reliability as the brightest object in our night sky. An adagio tempo and somber but strange melody make “Saturn” stand out as a unique movement in the suite, like the planet stands out in the solar system for its uniquely stunning rings. The dreamy harp and string melodies and surprise choir in “Neptune” portray the secretive aspect of the planet’s rich blue color, cold temperature, distance from Earth, and invisibility to the naked eye. The serendipitous accuracy of “The Planets,” along with its sonic beauty and engaging melodies, contribute to its timelessness.

Holst’s “The Planets” is a modern classic and an extraordinary work of art that inexplicably predicts the future. The brilliant, inspiring suite offers intimate insight into a private man’s mind and a spellbinding journey through space. Where “rational understanding fails,” “The Planets” fills audiences’ blanks with a moving, artistic experience.

—Staff writer Vivienne N. Germain can be reached at vivienne.germain@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.