News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

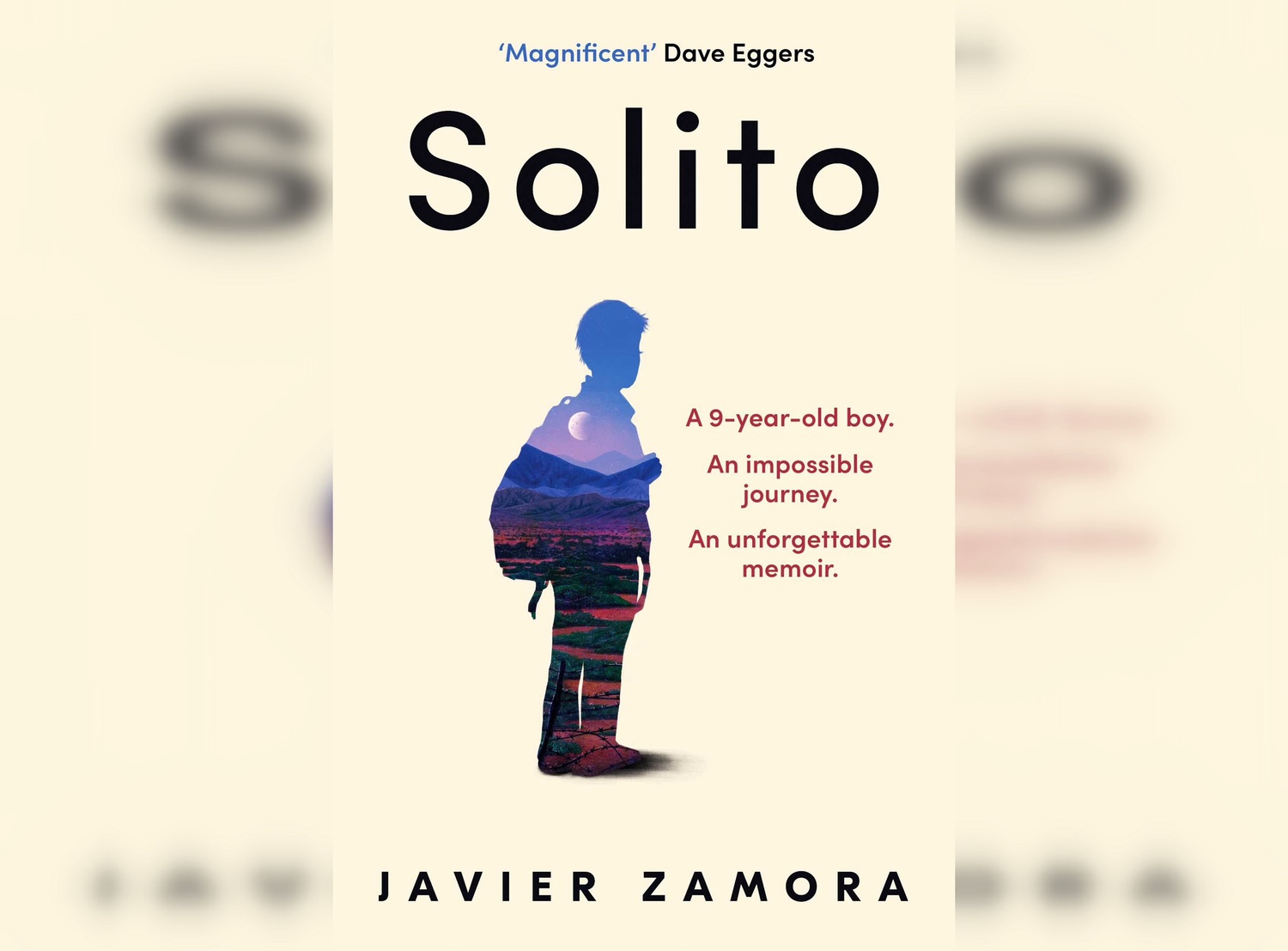

'Solito' Review: Is Empathy Enough?

4.5 Stars

Most of us don’t remember what it was like being nine years old. But not Javier Zamora: when he was nine years old, his life changed forever. In his debut memoir “Solito,” Zamora recounts the two harrowing months of his childhood he spent migrating alone from his family home in El Salvador to California in the heat of early summer.

For a memoir, the book encompasses little of Zamora’s life, focusing intently on the life he left behind in El Salvador — as a precocious student with a loving, quirky extended family — and Zamora’s odyssey to reunite with his parents, already living in the United States. Zamora’s love for his family, and the de facto family he joins along his route, is the beating heart of his story. Though the nature of a memoir is the life account of one person, Zamora gracefully and gratefully depicts all of the adults who raised him, aided him, and guided him throughout his treacherous, unforgiving journey.

At times “Solito” is difficult to read. Young Zamora faces down soldiers and border patrol, punishing desert treks, and encounters with unsympathetic individuals. The terrible beauty of the child’s perspective is his utter dependence on the kindness and care of others. As Zamora narrates the hardships he survived, the reader is left to grapple with the enormity of his situation and its apparent hopelessness; Zamora is just a kid, alone. Solito. And yet this is a story of immense hope. Zamora never loses faith that he will see his family again, and his trust in the good people around him leads to heartfelt moments of joy despite the terror and exhaustion surrounding his journey.

It is this focus on humanity and moments of quiet that sets Zamora’s story apart from other narratives of migration, though pigeon-holing this memoir as such feels reductive. While the focus of the memoir is Zamora’s journey to the United States, his attention to culture gives the book a powerful multi-national interest. Peppered through with Spanish phrases, “Solito” is a true bilingual text. Zamora attends to the subtleties between the slang and accent of El Salvador and that of Guatemala or Mexico. He explains, with childlike wonder, the experience of comparing Mexican food to his home country’s, and what it was like to share transport with migrants from across South and Central America. In doing so, Zamora calls attention to the differences between the frequent monolith “migrants,” humanizing and individualizing the people he encounters.

Zamora is best known for his poetry, which shows in his gorgeous descriptions of nature, borne at least in part, from childlike wonder and attention to detail. The audiobook, narrated by Zamora himself, at times takes on the lilt of spoken word, a feature that makes the story more immersive and heart-wrenching. For those who don’t speak Spanish, the audiobook offers an opportunity to glean intent from tone and inflection rather than pausing to translate. Zamora’s English writing often adopts Spanish grammar in a hugely successful formal choice that emphasizes the link between language and identity. Again, listening to the audiobook can help make this stylistic quirk mesh with the narrative flow more naturally.

The only challenge of this incredibly powerful story is repetition. Zamora attempts to cross the U.S./Mexico border several times, all of which are recounted in this book. It is factual recollection, and therefore not an issue that can necessarily be corrected, but the descriptions become unfortunately repetitive. Additionally, the level of detail is astonishing for a traumatic story from two months of Zamora’s early childhood that he admits to blocking out of his memory for quite some time. It seems likely that Zamora has taken liberties with retelling his story, which offers an opportunity to explain those choices that Zamora neglects.

The final note from present-day Zamora is what really sells this book as original and important. In it, he explains his rationale for writing this book, humanizing the narrative and contextualizing it within a sort of repatriation framework that sets this apart from other immigrant narratives. In many ways, “Solito” is the exact opposite of “American Dirt,” a highly controversial fictionalized account of the immigrant experience often ridiculed as “trauma porn.”

“Solito” is heartfelt and human, poetic and gripping, and as it is a true account, perfectly realistic. However, both “American Dirt” and “Solito” ask us to feel empathy for the horrors of the migrant experience in a plea for systematic change. But as more and more of these powerful stories become mainstream media, and the sensationalism of social media capitalizes on personal narratives to a numbing effect, we’re left to wonder: Is empathy enough?

—Staff writer Serena Jampel can be reached at serena.jampel@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.