News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

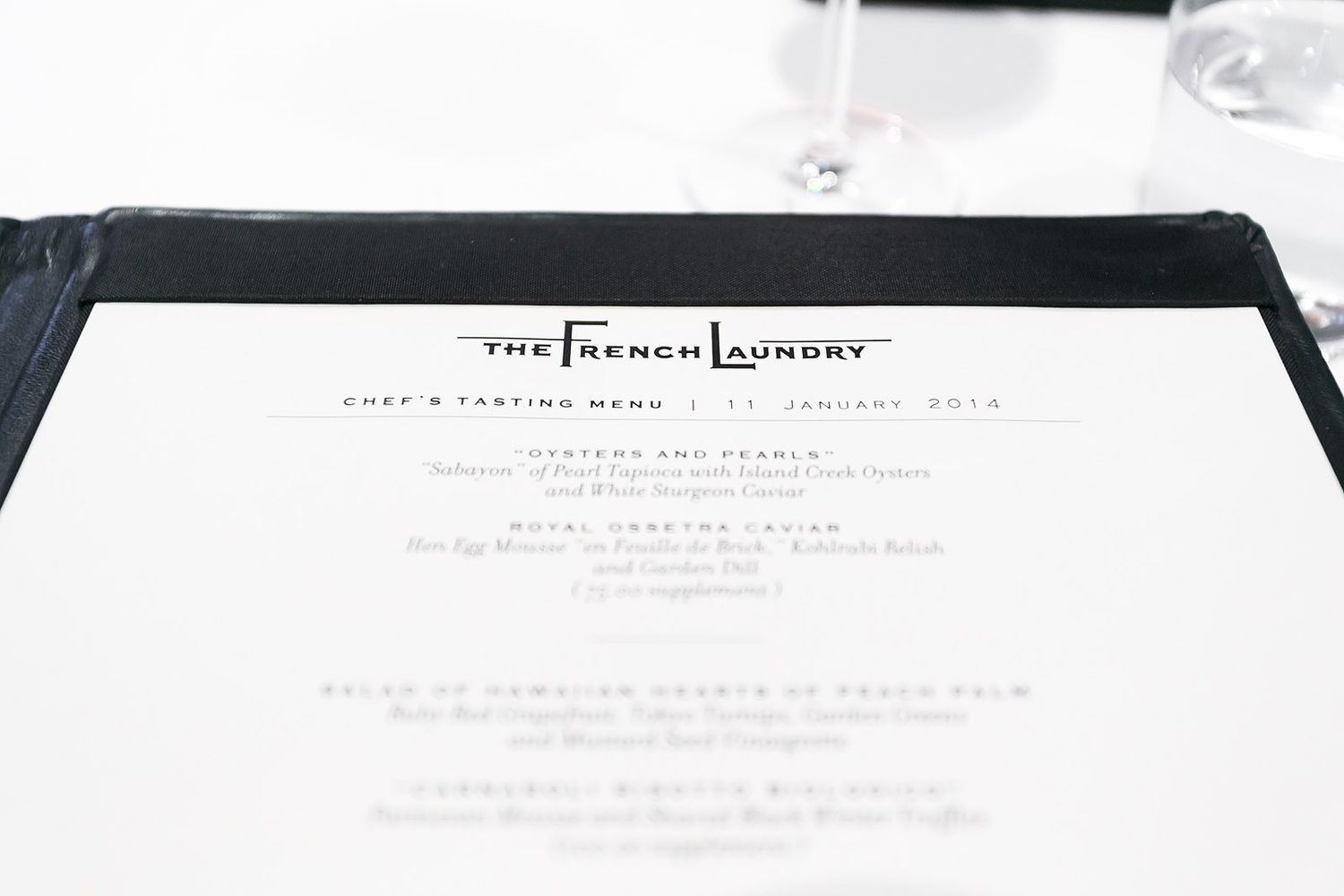

A Symphony of Flavors: Tasting Menus, Revisited

The position of the culinary arts within the world of creative expression is much like that of a 12-year-old in a college seminar. Our aspiring seventh grader, being the youngest person in the room, receives showers of attention, but the steely-eyed septuagenarian leading “Introduction to Sociology” treats him as an inferior. Similarly, cultural critics view the culinary arts as artistic, but not an art form in and of itself. They consider paying £255 for a meal to be ludicrous, but find coughing up $105 million for a five-hundred-year old sheet of fabric covered in egg yolk and colored powder to be a “bargain.” They complain about the most expensive restaurant in the U.S. charging $800 for a three-hour omakase experience, but voice no opinions about the going rate for first row seats at Sir Elton John’s farewell concert in Atlanta (Sept. 22, 2022): $9,729.

The debate is not about whether anybody should fork over thousands of dollars to experience art. Rather, this essay questions the arbitrary cultural bias against the culinary arts and the practice of “fine dining.” The present outcry against tasting menus is a case in point. To understand the crux of this argument, some context about the history and definition of tasting menus is necessary. From where did they originate? What distinguishes them from other forms of dining?

Although chefs have served lengthy menus highlighting signature dishes since the early 1900s, it was the French nouvelle cuisine movement of the 1970s that introduced the concept of a holistic culinary experience in which chefs dictated most, if not all gustatory decisions. Such esteemed establishments as Paul Bocuse’s “L'Auberge du Pont de Collonges” and Jean and Pierre Troisgros’ “Les Frères Troisgros” first coined the term “menu dégustation,” or “tasting menu.”

Based on the number of courses and the size of portions served, however, these early degustations did not resemble today’s tasting menus. Ferran Adrià’s “El Bulli” is the nearest culinary ancestor to the contemporary tasting menu. Beginning in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, diners at the institution were served fifty plus courses over five hours, each dish no more than several bites.

The basic unifying principle of all tasting menus is a reversal of traditional power dynamics between producer and consumer. At its core, a tasting menu format allows the culinary team to calibrate every element of the dining experience. If Grant Achatz decides to serve a Coronavirus-shaped canapé at his three Michelin-starred culinary stalwart Alinea during the height of the pandemic, every table will receive a bluish-gray half-sphere of coconut custard studded with freeze-dried raspberries. This authority is not immune to criticism. Like all artists, chefs are subject to praise and admonishment.

Critics oftentimes associate tasting menus with elitist institutions due to the prices at which they are offered. Yet, a multi-hundred dollar price tag is far from a requirement. Indeed, a growing movement of restaurateurs are offering tasting menus at the $50 to $100 range. This reduction is possible partly because providing a tasting menu actually decreases a restaurant’s expenses. Knowing the specific service menu and the exact number of reservations for a particular night informs restaurants’ supply orders. Venues that only serve a tasting menu thus reduce food waste, and, consequently, their operating costs. The savings associated with offering tasting menus often allow restaurants to provide livable wages to employees, too. For instance, at Somerville’s Juliet, minimum hourly compensation is fixed at $16, irrespective of tips and service-charge. Moreover, a raise is guaranteed after working at the restaurant for one year. In the best case scenario, owners, employees, and diners all benefit.

Still, Despite the growing movement towards more affordable tastings, profit mongering still exists at restaurants exclusively serving degustation menus. Moreover, the revenue earned by posh restaurants such as Blue Hill at Stone Barns does not necessarily lead to higher wages and better working conditions for restaurant workers. However, these are issues that plague the entire hospitality industry, not just restaurants serving tasting menus.

So, what about tasting menus in particular disgusts so many cultural commentators? The culinary freedom given to chefs and their teams.

According to Executive Director of the Food and Society policy program Corby Kummer, the leaders of the tasting menu movement are “a new army of fresh-faced Stalins” that “prepares to spread tyranny across the land.” The diner, Kummer writes, is “like a theatergoer, a passive participant in a spectacle he can either like or lump.”

By that logic, however, every concertgoer should riot at the possibility of a set program. Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony? Why not change that to Mahler’s Second for the evening? That’s treason!

In every field of expression generally recognized as an “art”— think music, drama, dance, and the visual arts — the creator’s imagination is held sacred: ars gratia artis. Yet, in gastronomy, “art for the sake of art” apparently goes by a different name: totalitarianism. Sure, patronage exists in all forms of creative expression. Nowhere else, however, does the patron determine the product like in the culinary artists. It is time to grant culinary artists the respect they deserve. Just ask the 12 year old.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.