Some Affiliates Call Out a Racial ‘Double-Standard’ in Harvard's Response to the War in Ukraine

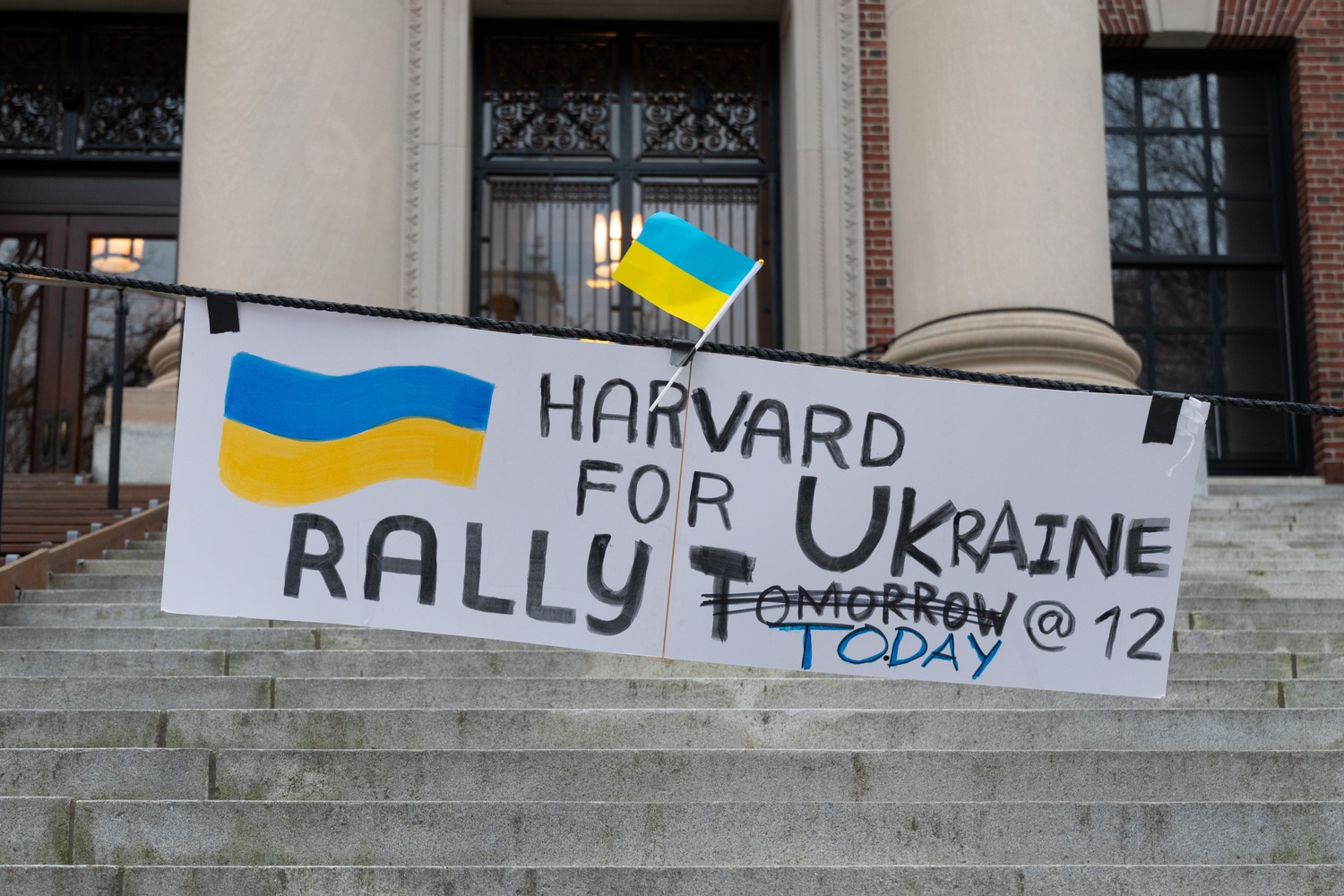

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last month was met with a swift response on Harvard’s campus, with rallies, petitions, and statements of support.

However, the tide of Ukrainian solidarity on campus has left some students and faculty disappointed with the lack of public response at the school to other similarly devastating wars and crises that occur in non-predominantly white and Christian countries. Some students and faculty say the more vocal response at Harvard to the war in Ukraine reflects a racial double standard.

Just four days after the invasion, Harvard University President Lawrence S. Bacow wrote, “Today the Ukrainian flag flies over Harvard Yard. Harvard University stands with the people of Ukraine.”

In response to the University’s tweet announcing its hanging of the flag, Joelle M. Abi-Rached, lecturer on the History of Science, wrote in a reply, “Great. But I wish @Harvard also stood so publicly and swiftly with all oppressed people of this world: Kashmir, Iraq, Yemen, Palestine and esp. Syria that was destroyed by the same war machinery now deployed in Ukraine.”

By not consistently taking a stance on other global conflicts, Abi-Rached says, Harvard sends a message to victims of conflicts in predominantly non-white populations that “their lives do not matter” and are “not equally valued, they are unworthy of the same concern, the same outcry, the same respect.”

Growing up in Lebanon, Abi-Rached had to flee her home on multiple occasions amid violent conflicts.

“I would personally have appreciated more ethical consistency [from Harvard] and not feel as a second-rate or lesser human being because I don’t come from a country at the doors of Europe where people are blond, blue-eyed,” she says.

Abi-Rached urges others to point out the University’s inconsistent stances on international conflicts.

“I think it behooves us to criticize and to speak out and be vocal when there is a double standard,” she says.

After several conversations with Abi-Rached, vice president of the Harvard Islamic Society, Sameer M. Khan ’24 penned a statement on behalf of the organization in support of Ukraine.

After stating the Society’s solidarity with the Ukrainian people, the statement reads, “As a Muslim community, though, we know too intimately that Ukraine is not the sole face of these ills — of colonialism, of ethnic violence, and of militarization.”

“Our Black and Brown bodies are too infrequently offered the spotlight in moments of crisis and catastrophe,” the statement continues.

“Ultimately, to condemn occupation and militarization in Ukraine requires us and all those committed to preserving human rights to condemn occupation and militarization everywhere: in Kashmir, Tigray, Palestine, Yemen, Iraq, Afghanistan, the United States, and far beyond,” Khan wrote.

Khan, who is from Kashmir, a region he describes as also facing “militarization, occupation, and colonialism,” highlights that the purpose of the statement was not to detract from the Ukraine invasion, but instead, was intended to “hold space for Ukraine and…care for Ukraine while also configuring to uplift communities — like the people of Kashmir, the people of Tigray, Syria, Palestine, and beyond — that continue to face colonialism, but don’t always have the luxury of watching and having the world stop for them.”

“Our attention should be distributed equally and unselectively,” he adds.

Afghan student Muqtader Omari ’25 says Harvard’s response reflects a “clear bias.”

After the Taliban took control of Afghanistan on Aug. 15, 2021, Omari had to leave his home country and move to campus early for his freshman year. While Harvard was accommodating in terms of providing him with housing and an earlier move-in date, he says it was still “a disappointment to know that they could have done so much more but chose not to, until the Ukrainian situation.”

“If Harvard had the capacity to do this much, why did they choose to stay silent in conflicts in non-white and non-Christian countries?” he adds.

Harvard spokesperson Jason A. Newton declined to comment on these criticisms.

Despite Omari’s frustration with the University’s muted public response to other global conflicts to the extent that it has with Ukraine, he notes that he feels most disappointed by the reactions of his fellow students.

“This crisis portrayed the worst in Harvard students,” Omari says. He says he asked students about why they chose to publicly support Ukraine now when they did not support the people of Afghanistan just months ago, and he received responses filled with “racist rhetoric about how one felt ‘closer to home.’”

According to Omari, students he talked to overlooked the reality that both wars had devastating consequences, instead emphasizing minor differences between them. Omari sees the only difference as the color of the victims’ skin — which “just basically highlights the racism that’s going on in our campus,” he says.

Omari says he was saddened by “seeing Harvard’s student body — who acts so socially liberal — to just completely be so racist and disregard one conflict and then publicly support another.”

Omari emphasizes that he does not take issue with the University or its students responding to the war in Ukraine, but he does take issue with the double standard created by not publicly supporting its Afghan students and other non-white victims of war and conflict.

Echoing Omari’s sentiments, Ukrainian student Nika O. Rudenko ’24 calls the University’s lack of response to other conflicts “immoral.”

“I’m 100 percent confident that Harvard should have done whatever they’re doing right now for Ukraine to any other country,” she says.

Rudenko believes activism on behalf of Ukrainian students is not just geared towards securing greater support and resources from Harvard for them.

“Right now, we are trying to establish a precedent so that not only Ukrainians or any person who is affected by the current war receive the necessary support within the University, but also [so] every other student who is going to be affected by any conflict in the future will have the same support system provided to them,” Rudenko says.

— Ciana J. King contributed reporting.