News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

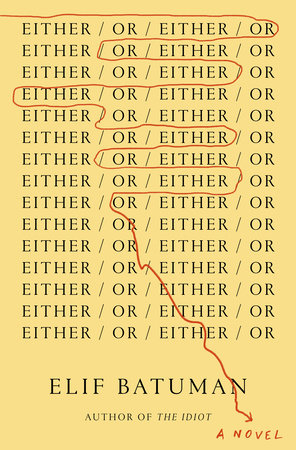

‘Either/Or’ Review: The Older and Sexier Sequel to ‘The Idiot’

3 Stars

With her debut novel “The Idiot” having been crowned a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize in Fiction, Elif Batuman set towering expectations for the sequel “Either/Or.” Beginning where the first novel left off, Harvard College sophomore Selin Karadağ realizes she has reached the age where the contemplation of love is absolutely vital. In her youth and her “overprivileged” position at Harvard as a Turkish immigrant’s daughter, this newfound obsession means a tangle of personal grief, classic literature, Freudian psychology, and the self-centered agonies of a college student. However, overbearingly well-read and obnoxiously far from self-aware, Batuman’s protagonist is hard to love and even more difficult to trust.

Both “The Idiot'' and “Either/Or'' evoke Batuman’s own life, fictionalizing and re-casting the autobiographical. Selin and Batuman are both daughters of Turkish-Americans raised in New Jersey and attending Harvard College to pursue literature, and Ivan, Selin’s persistent object of desire, is a narrative iteration of Batuman’s own 18-year-old crush.

Batuman’s “Either/Or” is a labor of love and practice in reflection, split into Fall Semester, Spring Semester, and Summer. Time seems to pass without consequence inside Selin’s matter-of-fact narration. Days are slow but weeks fly by. Obsessive fixations on Ivan, on partying, and on her roommate’s beauty fade in and out, eclectic and paradoxically insignificant. There are points where life is beautiful, where the anxieties of being loved and desired become all too relatable, and where Kierkegaard’s “aesthetic life” seems to hold all the answers. Yet “Either/Or,” while mirroring its predecessor’s structure, fails to capture the charmingly infuriating naïveté of Selin and instead drags readers through an overly familiar tale shoved through the lens of a Harvard student. Any relatability that a growing, insecure Selin might have, even the tragedy of losing a best friend to an all-consuming relationship, is thwarted by her persistent inability to perceive accurately and empathetically. Instead, she works overtime to map her own life onto Russian literature.

It is hard to not look upon parts of this book with affection, especially when writing from the very same Quincy dining hall Selin frequents. But despite Batuman’s references to Mather’s objective ugliness and the BDSM-themed parties of a certain literary magazine, she perhaps plays too far into the expectation of a Harvard student’s psyche and the collection of individuality complexes gathered here. Anxieties of a university student are bogged down with literary allusions and self-aggrandizing proclamations of growth, evoking the trope of a Harvard student in hasty, reductive explanations of André Breton and the categorical imperative.

These gaps are perhaps a symptom of the book’s distance from the experience that inspired it. Batuman began “The Idiot” a few years after graduating Harvard but did not write “Either/Or” until turning 40. Sentimental observations of “how brief and magical it was that we all lived so close to each other and went in and out of each other’s rooms, and our most important job was to solve mysteries” speak more to the meditations of a seasoned adult than a depressed and naïve college sophomore. Youth is no longer a source of great curiosity and odd charm, but a sin Selin is not aware she is committing.

A nerdy child of immigrants in a New Jersey high school, college Selin finds herself intoxicated by newfound male attention, sexually liberated in some instances and painfully unaware in others. Her intellectual, emotional, physical, and sometimes psychological obsession with sex is just another bend in her all-important journey to adulthood, with subsequent sexual encounters fading into Selin’s distinct narrativizing of her summer traveling project.

The greatest pause Selin (and this book) fails to take is a moment of critical thought for the many instances of sexual assault and harassment she encounters and perceives. Perhaps Selin is all too unaware to register her friend Lakshmi’s assault or her own brushes with violence, or perhaps her dismissive descriptions result from her lack of vocabulary. Regardless, Selin’s inability to articulate their implications does not play into her favor nor her likeability. In her own biographical description, Batuman does acknowledge Selin’s journey takes her “to some pretty dark places, which she takes to be unavoidable and part of the rich tapestry of life” and asks readers, “but are they?” Yet for all the conversation of French feminist theory in Selin’s life, a conversation about consent and intent is strikingly absent — even for a ’90s college campus.

Batuman is certainly the writer Selin aspires to be: exceptionally talented, obviously well-read, risk-taking, and recognizably unique. And in many ways, that distance of age prevents an older, wiser, contemplative Batuman from accessing Selin’s voice with authenticity. However, self-reflective insights and witty allusions still populate the text, and readers will find a fruitful exercise in young love, identity, and philosophy.

“Either/Or” is available on May 24th, 2022.

—Staff Writer Hannah T. Chew can be reached at hannah.chew@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.