News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

‘The Light We Carry’ Review: Michelle Obama’s Diplomacy For The Soul

4 Stars

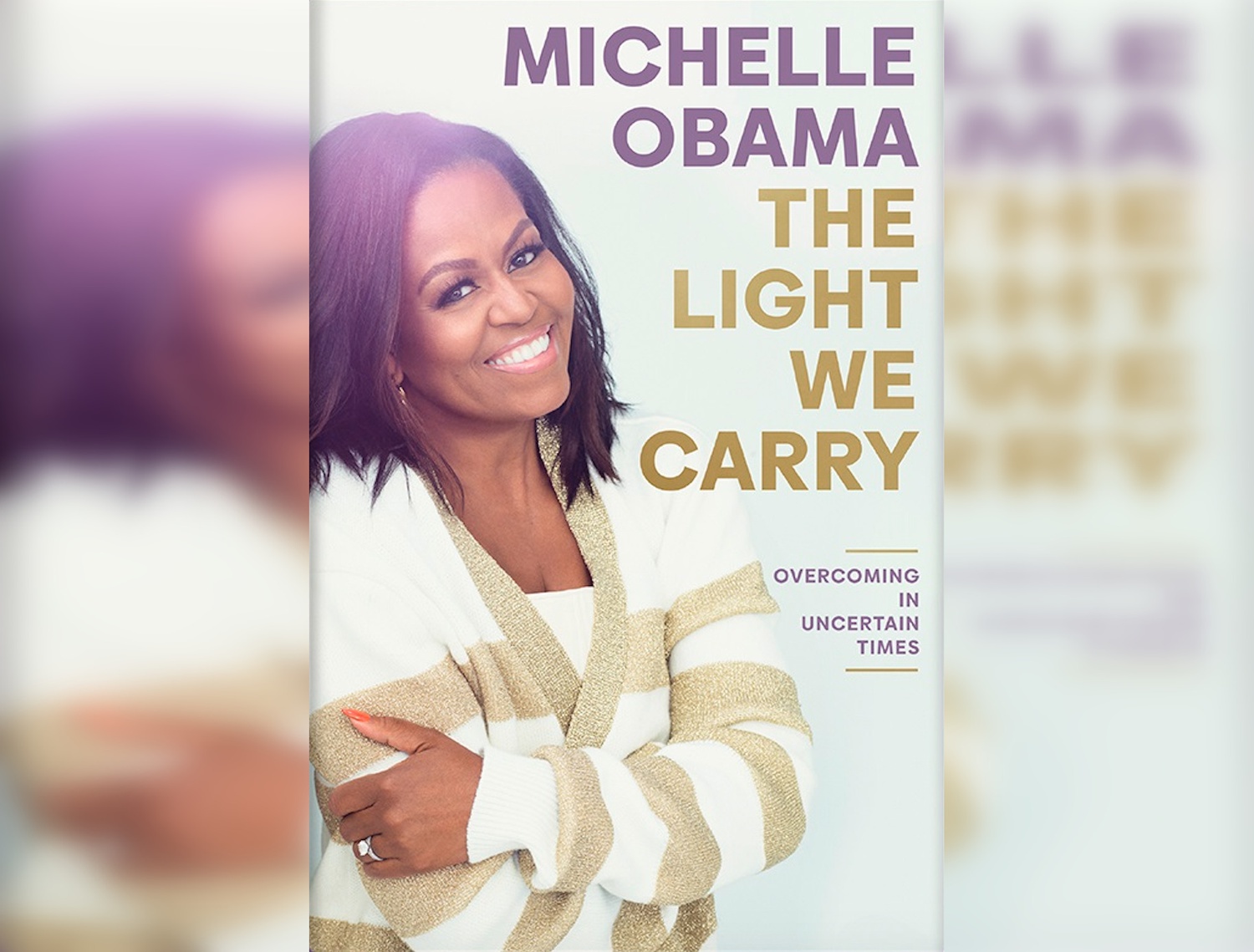

In her infamous 1968 portrait of Nancy Reagan, Joan Didion described in excruciating detail Reagan’s “interested smile, the smile of a good wife, a good mother, a good hostess.” It was, Didion wrote, “the smile of a woman who seems to be playing out some middle-class American woman’s daydream, circa 1948.” On paper, beaming out from the cover of her new book, Michelle Obama might be described in similar terms. Yet the difference between the two first ladies is intuitive and immediately obvious: When Obama smiles, she crinkles her eyes. Her cheeks dimple, her head tilts in a subtle gesture of welcome. In other words, unlike Didion’s Nancy, she seems real.

It is that realness which buoys up “The Light We Carry: Overcoming in Uncertain Times,” Obama’s latest book. In it, she offers “a glimpse inside [her] personal toolbox” for navigating the world. “The Light We Carry” is an eminently undemanding read, accessible to both the mothers who consider Obama a contemporary and the daughters who regard her as a role model. The prose is straightforward — nothing fancy — and personable. It is easy to digest all at once or over several sittings: Each chapter is divided (by a fitting, if slightly trite, sunburst symbol) into short sections, most of which could easily stand alone as an op-ed or, in her less graceful moments, a self-help article.

In “The Light We Carry,” Obama delivers a series of simple maxims, bite-sized (and occasionally meager) fillings wrapped in a thick layer of anecdote. These walk the line, only partly successfully, between simplicity and banality. Sometimes it stretches into hackneyed territory, as when she advises her readers to “see your obstacles as building blocks and your vulnerabilities as strengths.” Ultimately, many of her lessons land; her musings on the importance of gladness — which Obama calls the “extension of curiosity from one person to another” — are especially welcome.

Obama discards entirely the Nancy-esque veneer of domestic perfection. Indeed, by her own admission, she has made “a fairly deliberate effort to blow holes in the myth” of her utopian life in the White House. Of course, that only further bolsters her credibility. But there are still some elements of life in the Obama household which are just too good to be believed, as when she writes: “There is no quicker or more efficient way to obliterate stress… [than] a hard-core, edge-pushing workout.” This sort of vigorous sentiment, in combination with Obama’s trademark optimism, starts to feel dubiously relatable after a few more fitness metaphors. It calls to mind a 2009 headline by that stalwart of satirical news, The Onion: “Happy, Healthy Obamas Out Of Touch With Miserable Americans.”

Writing two books that address the same subject — particularly in the case where that subject is the author’s own life — is a difficult thing to do well, and even more so within a short time span. Didion managed it by confining her reflections to specific people and moments in her life; Frank McCourt, by dividing it up by the era of his life. Obama does neither in revisiting nearly every theme explored in her 2018 best-seller, “Becoming”: her childhood, parents, career, marriage, and experience in the White House, all from a very similar perspective and with a very similar tone. Perhaps the major difference is that in “The Light We Carry,” she tells the reader exactly what lesson they ought to take away from her anecdotes. The effect is slightly grating; only Obama’s immense charisma and obvious goodwill in proffering this advice keeps it from tipping into condescension.

Much of “The Light We Carry” may resonate deeply with readers, including Obama’s reflections on parenthood and friendship. But, over and over, the book runs into the same problem: It feels real, but it doesn’t feel substantial. Nearly every part of the book that is not personal anecdote reads as if it could have been written by anyone (and indeed, taking Barack Obama’s wry “ghostwriter” comment at face value, it might just have been).

Still, “The Light We Carry” is a performance worthy of a First Lady — genuine, easy, intimate, but one which keeps the reader at arm’s length, just far enough to stay real. It lacks the vibrancy of detail and the vulnerability of “Becoming,” but gains a kind of clucking maternal stateliness as a result. The word that springs to mind — despite its stuffy connotations of handshakes between dour men in suits — is diplomacy. And even Didion might not object to that.

—Staff writer Mira-Rose K. Kingsbury Lee can be reached at mirarose.kingsburylee@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.