Treeland: The High-Rises Harvard Never Built

In the 1970s, the University was primed to build an immense graduate student housing complex in the Riverside neighborhood — until grassroots resistance led it to scrap the project altogether. It was the last time Harvard tried to expand into Cambridge.

Treeland: The High-Rises Harvard Never Built

In the 1970s, the University was primed to build an immense graduate student housing complex in the Riverside neighborhood — until grassroots resistance led it to scrap the project altogether. It was the last time Harvard tried to expand into Cambridge.On June 11, 1970, Harvard’s 319th Commencement ground to a halt.

Graduating senior Steven J. Kelman ’70 was delivering a speech where he talked about the “oppressed people of the world,” Saundra Graham recalled.

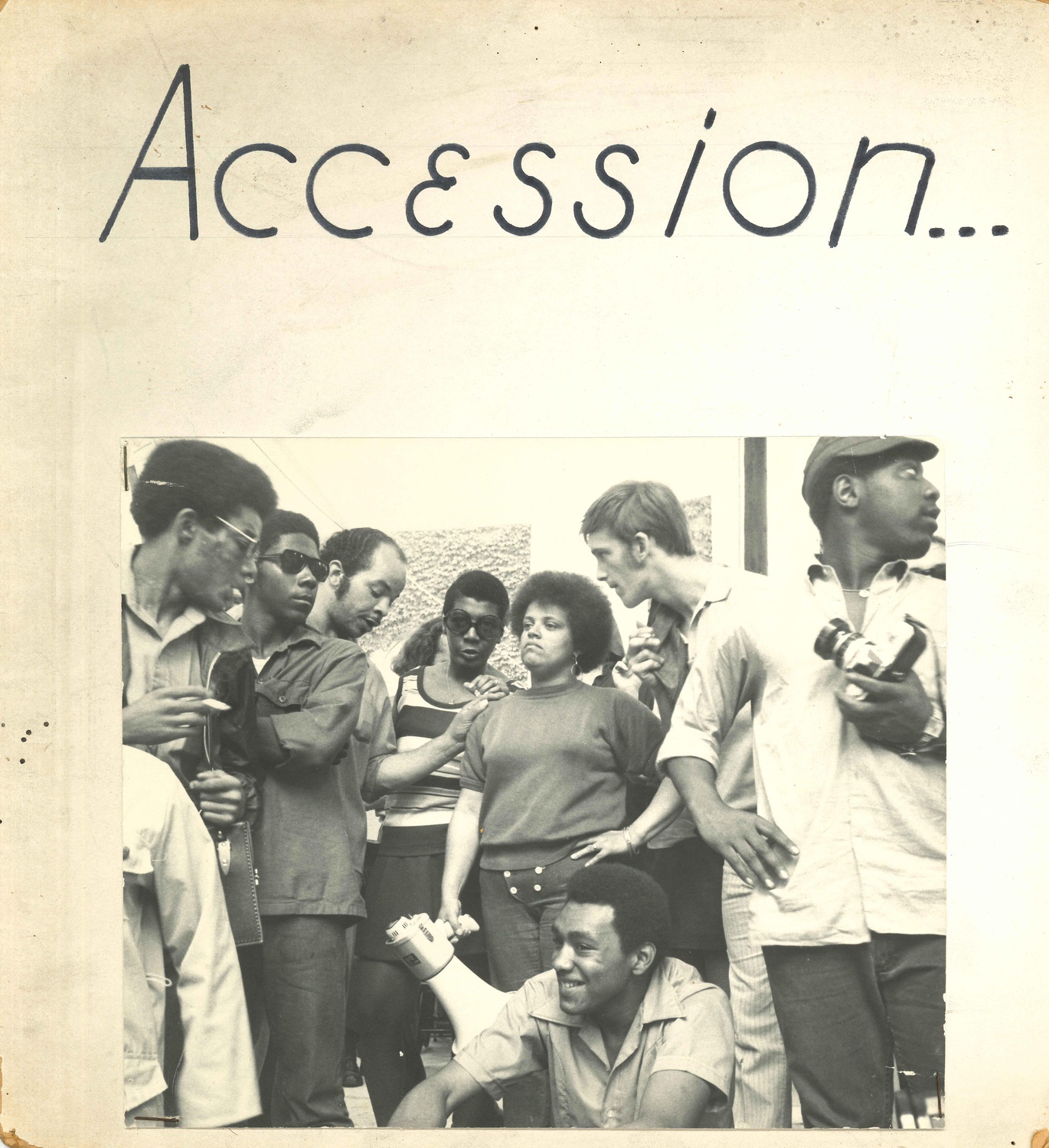

“Hell, he’s looking at them,” she thought. “But he ain’t talking about us.” So Graham, a Cambridge resident — 28 years old, wearing jeans and a red t-shirt, and several heads shorter than the administrators behind her — jumped over a row of chairs with a bullhorn in her right hand. A dozen activists holding protest signs followed her onstage, pushing past deans in graduation regalia and top hats.

Graham remembers that President Nathan M. Pusey ’28 tried to pull the microphone away from her. “Get the hell away from me,” she told him, “or I’ll punch you in your face.” When the power was cut anyway, she switched to her bullhorn.

“We are here to demand that Harvard University give to the residents of the Riverside area Treeland,” she said to the crowd, “so we can build low-income housing for the poor people of Cambridge.”

Treeland was a planned Harvard graduate student housing complex with two towers, 15 and 22 stories tall. It would be built on the Treeland-Bindery site at Memorial and Western, the latest in a series of University developments into Riverside, a working-class neighborhood southeast of the Square. Riverside, also called “Coast” in a nod to its Caribbean immigrant roots, had been home to a substantial Black community for 200 years.

The day before Commencement, Graham and the Riverside Planning Team, a housing activist group, had intended to take their demands directly to the Harvard Corporation, the University’s highest governing board. Close to 350 tenants, mostly mothers and their children, marched to the Yard on June 10, asking to meet with Corporation members.

“Part of the problem,” Graham told the Record American before the demonstration, “is that we’ve been getting commitments from Harvard that aren’t commitments at all.”

None of the Corporation members would meet with them, so the team decided to wait. Though some undergraduate students offered to host them in their dorms, the 75 members of the team opted to camp out in the Yard instead, sleeping under tents in the southwest corner.

On the morning of Commencement, the team again asked to meet with Corporation members, Graham recalls. They heard nothing. Seeing few options for getting through to Harvard’s decision-makers, the group decided to stage a protest during the event.

“We have been here longer than you’ll ever be here,” Graham continued through her bullhorn, to an audience split between cheers and boos, “and we’re not going to move because of you.”

Eventually, Pusey stepped back up to the mic. “Members of the Harvard Corporation have very generously volunteered to go to University Hall to meet with this group — in which case we go forward,” he told the crowd to applause.

Several members of the Harvard Corporation sat down with the activists in a lecture hall to review their list of demands. After hours of deliberation, they reached an agreement. The University would commit to building low-income housing — but not on the Treeland site, Graham remembers them telling her. “They told us that the land was too valuable for low-income people,” she says.

But by October 1971, Harvard had scrapped its plans for the enormous housing development, in part due to months of pressure from Graham and her team. Today, a public park stands where Treeland would have been.

Graham — who later became the first Black woman on the Cambridge City Council, as well as the first Black woman to represent Cambridge in the state legislature — is 81 now. When we knock on the door of the Riverside home she has owned for 45 years, she answers in a fuzzy gray robe.

She still goes to community meetings, and she still says exactly what she thinks. Of the Corporation members she met with after the Commencement protest, she says, “Their faces were blank, like they’d never heard of low-income people.” And of Riverside now?

“The community is gone,” Graham says. “There’s only a few of us left.”

Today, Harvard students may know Riverside as the neighborhood they have to walk through to get to Whole Foods, full of leafy streets and renovated homes. Despite the success of activists like Graham in halting Harvard’s development there, other forces — like growing student populations, aggressive real estate development, and regulatory changes like the end of rent control — continued to gentrify the neighborhood and push residents out.

But the Treeland fight still marked an important episode in both Riverside and Harvard’s history. The fight was a rare instance of grassroots activism that derailed a major project over just a year — and just about the final episode in Harvard’s expansion in Cambridge.

Hundreds of archival Harvard documents, recently unsealed after a 50-year moratorium, and interviews with longtime Riverside residents illustrate the rise and rapid fall of the Treeland project. They depict the impact sustained activism had on a powerful university eager to expand, yet equally wary of negative publicity.

As the University has developed in Allston, it has used similar techniques to gain a foothold, even as it has made a concerted effort to incorporate community input. Understanding what happened in Riverside may cast light on Harvard’s continued expansion, across the river and into the 21st century.

'Harvard, Urban Imperialist'

President Pusey and Edward S. Gruson, an aide in charge of community affairs, sat down to lunch on Sept. 16, 1970. An avid birdwatcher and fan of a “four-martini lunch,” Gruson was Pusey’s eyes and ears as Harvard navigated real estate development in Cambridge. Over lunch, they discussed the shortage of University housing for Harvard graduate students — and how the already-planned Treeland development might provide a solution.

In an October 1970 letter recounting the lunch to a city councilor, Gruson cited some startling statistics: Due to a shortage of University housing, 3,655 of Harvard’s 8,360 graduate students lived in private rentals across Cambridge. Counting faculty members, Harvard affiliates were estimated to take up 2,238 city apartments — about 6 percent of the city’s housing stock in 1970.

To make matters worse, University affiliates who lived off campus were driving up rents for other residents. An internal report from 1968 found that “persons connected with the university, or seeking to live in its shadow, have bid up the price of housing at an astronomic rate.” Faculty members and groups of students, the report said, could vastly outspend local families on rent. The city recognized rising housing costs as an issue, too, instituting rent control in 1970.

With these issues in mind, Gruson’s 1970 letter continued, new housing construction was necessary to “decrease the pressure on the existing housing supply of the City.”

So Harvard looked to the Treeland-Bindery site, which had once held the Harvard University Bindery and the Treeland Christmas tree nursery. The bindery had moved to that location in 1930, but was relocated in 1958 after decades of financial distress. Until at least the 1950s, the nursery was run by Raymond S. McLay, called the “Christmas tree man” for his practice of delivering hundreds of free Christmas trees to children whose families could not afford them.

The Treeland proposal would have added to Harvard’s string of buildings that towered between the neighborhood and the Charles, following Peabody Terrace, a married graduate student housing complex built in 1964, and Mather House, which wrapped up construction in 1970. The projects took advantage of unlimited-height zoning districts that Harvard had spent years campaigning for, and which the city established in 1962.

In addition to viewing development as important to increase student housing options, administrators framed it as advantageous for the surrounding areas. As the Harvard Planning Office claimed in a 1960 report: “A university has a recognizable, beneficial effect on the economy of a community. This fact can well be observed in Cambridge. Property tends to improve as it is located closer to the University.”

But this optimistic statement elided the details of what “improvement” looked like for longtime tenants, something activists frequently emphasized.

A 1969 pamphlet published by an anti-ROTC group, titled “Harvard, Urban Imperialist,” quotes Pusey as saying: “Harvard preceded Cambridge and is the most important thing going on here.” In a narrow sense, this was true; Harvard became a college before Cambridge became a city. But for the most part — in areas like Riverside, as well as Kerry Corner, the adjacent neighborhood named for its Irish immigrant population — Cambridge preceded Harvard. And to build the sprawling university it envisioned, Harvard-as-developer needed to push longtime residents out.

Before the 1930s, the area where the River Houses now sit was also part of Kerry Corner. Working-class Irish immigrants’ homes, which a Harvard alumni organization called “a poor class of property,” lined Mill, Plympton, and Dunster Streets, which were often called “the marsh” for their closeness to the river.

The construction of Lowell, Dunster, and the Malkin Athletic Center in the ’30s required demolishing 59 houses. In 1924, a local priest lamented that construction had displaced “a Catholic population estimated at 1,200-1,500 souls,” according to Susan E. Maycock and Charles M. Sullivan’s “Building Old Cambridge.”

This process accelerated when Pusey became University president in 1953; his tenure was an “era of prolific building,” Maycock and Sullivan write.

In 1956, “Harvard started buying all the property it could get its hands on,” says an activist in the documentary “Left on Pearl.” “And if they were two- or three-family homes, they would evict the tenants.”

To build Leverett, Quincy, Mather, and Peabody Terrace, Harvard destroyed 104 more buildings. In all, the construction of the new House system and Peabody Terrace evicted and displaced more than 300 families.

When Harvard purchased a new building in a residential neighborhood, it did not always demolish it immediately. In a process called “landbanking,” the University sometimes acquired land and sat on it, often forced to wait the better part of a decade to buy up all the houses on a block before eventually razing them to make way for new Harvard buildings. Often, the University used shell companies to buy up land, concerned potential sellers would hike prices if they knew Harvard was buying.

In the meantime, since Harvard had no incentive to maintain buildings on its new landbanked acquisitions, it let many of them deteriorate. In 1978, The Crimson wrote that “landbanking can potentially turn an owner into a slumlord; the building is only secondary to the property value.”

“Harvard was a shitty landlord — because they didn’t keep up the buildings,” recalls Judith E. Smith ’70, then an undergraduate at Radcliffe involved with feminist organizing.

Harvard used landbanking and demolition to take over entire city blocks, where it could then construct new buildings. These practices were employed when building Peabody Terrace and Mather House, too; Riverside residents were displeased but presented little formal resistance.

Yvonne L. Gittens, a lifelong Riverside resident, jokes that her neighbors hoped Peabody, an immense, Brutalist complex, would “fall into the river.” According to one study, Peabody’s architects could have fit the same amount of units and parking in four-story buildings, rather than its 22-story, three-tower footprint — that is, the structure’s excesses stemmed less from necessity than aesthetic preference. Some Black and Irish families felt they had been “pushed aside to make room” for the construction of Mather in 1970, The Crimson wrote in a 1995 retrospection.

But despite this discontent, opposition was rarely vocal. Riverside residents “weren’t organized then,” Graham says.

The University had no reason to believe its next housing development would face any substantial pushback. In fact, according to Harvard Professor Suzanne P. Blier, who teaches a course on the history of Harvard Square, Mather’s construction came with an aura of authority; she describes Mather’s location on the border between Harvard and the surrounding communities as communicating that “We are here and we’re here to stay.”

Harvard began to move ahead with its decades-old strategy of landbanking and wrecking-ball development to build Treeland, one of its most ambitious projects to date. “Harvard had bought up the whole front of the river,” says an activist in “Left on Pearl.” Treeland would be the final piece.

'One Thing After Another'

Saundra Graham knew she had to do something. Growing up in Riverside, she had watched landlords evict her neighbors in dramatic scenes that played out on the street. “They were screaming, they were crying, and they all had children,” she says.

Sometimes, landlords would throw their tenants out in hopes of selling to Harvard. In the 1960s, it was Graham’s own mother who got an eviction notice. “When [the landlord] found out Harvard was looking to buy, he emptied his building,” she says. This experience helped fuel Graham’s activism in the 1960s.

The late ’60s were “tumultuous,” Graham says. “It was one thing after another after another, and people were getting tired.”

Graham herself had participated in another series of protests against a city proposal to build the so-called Inner Belt, an eight-lane highway that would have cut through her backyard. In its form proposed in 1962, the Inner Belt would have destroyed 2,200 housing units and displaced as many as 13,000 people.

In May 1967, 78 adults and 25 kids rode a bus from Cambridge to Washington, D.C., to meet with members of Congress about the proposed highway. As Cambridgeport resident Anstis Benfield recalled in a 2022 Cambridge community history conference, the kids spent all night singing:

Cambridge is a city, not a highway.

They will never build roads through our homes.

So we are going to stop the highway

And beat the Belt, beat the Belt, beat the Belt in Washington.

Benfield described participating in years of protests that met at first with resistance. After residents nailed petitions to the doors of City Hall, the city replaced the wooden doors with glass ones.

But by 1969, after a 2,000-person march to the State House, Massachusetts Governor Francis W. Sargent expressed something close to regret over his role in planning the highway years before. “I want you to know, we will not place people below concrete,” he said. “We are going to place concrete below people.” In 1971, Sargent rejected the Inner Belt proposal entirely and announced that the money saved would be put toward mass transit.

Community organizing against the Inner Belt paralleled the pushback Harvard began to receive from its working-class neighbors in Boston. While the Inner Belt was scrapped, Harvard continued developing. In the late 1960s, Harvard purchased a huge swath of land near the present-day Brigham and Women’s Hospital campus in what was then Roxbury, intending to expand existing Medical School and hospital facilities. As the University moved to evict the tenants and demolish their homes, residents began to organize with Harvard students.

The Roxbury Tenants of Harvard, an advocacy organization, called on Harvard to prioritize displaced residents in the new housing it was building. In a November 1969 letter, Robert S. Parks, the organization’s president, pressed Gruson, Pusey’s aide for community affairs, to budge on points the group deemed unacceptable: high rents and apartments too small to fit larger families.

What Harvard considered “affordable” rent still posed “a great hardship for many low-income families,” Parks wrote. “This,” he asserted, “is not low-income housing.”

In the end, Harvard demolished some homes, replaced them with high-rise towers, and offered some relocation assistance to those displaced. Families who had their home destroyed and were forced to relocate to a new high-rise were offered $400 — the equivalent of a little over $3,000 today.

In Riverside, discontent was beginning to mount. “We were just being chased all over the place by Harvard,” Graham says. “I said, nuh-uh, this has got to be a David and Goliath — we’ve got to get them somehow.’”

As the looming Peabody and Mather cast long shadows over the neighborhood, and evictions kept coming, Graham and her neighbors started to informally organize. “If we knew someone was getting evicted, we would call [each other],” she says, in an attempt to stop the eviction from occurring. She also worked with Harvard students, who informed her of the latest on the University’s development plans.

Around the same time, student activism on campus was reaching a fever pitch. In 1969, Pusey had ordered a violent police crackdown on students occupying University Hall to protest ROTC and the Vietnam War. In the spring of 1970, members of Students for a Democratic Society across 416 campuses went on strike; at Harvard, they advocated for anti-war demands, a Black Studies department, and an end to expansion into Riverside.

In April of 1970, an anti-war protest swelled to a 3,000-person riot on Mt. Auburn Street, where 300 people were injured. In the fray, students pelted nearly 1,200 police officers with bricks and rocks. The police responded by firing tear gas into Quincy and Lowell courtyards and into the interior of Adams House, where, The Crimson wrote, “gas fumes choked students in Claverly.”

1970 represented a climactic point for activism on and around campus, the culmination of years of pressure on Harvard to concede to myriad demands. Police crackdowns on student protests were met with shock and anger — Pusey would resign a year later — contributing to a heightened sensitivity around bad publicity. Harvard’s real estate model had not changed; it was still eager to complete its vision along the riverfront. But over the previous decade, organizers had built coalitions, sharpening their organizing tools, learning what worked.

When Graham and other activists began to protest against Treeland, it was this environment that fed their fight. As their demands and tactics came into closer focus, they put Harvard on the defensive.

The Rise and Fall of Treeland

A few months before the Planning Team marched on Commencement, Gruson already seemed concerned.

In a March 1970 letter to then-professor Archibald Cox, he voiced worries about the influence of new “community organizers,” whom he feared would allow Harvard’s neighbors to “develop a new militancy based on a ‘black–brown coalition.’”

In its previous construction projects, Harvard had kept close tabs on resident pushback. In a 1970 letter about a community meeting for a West Cambridge development, Gruson wrote: “We will have people there although we are not invited,” adding that he hoped to “handle it at a low noise level.”

When Riverside activists began meeting with Harvard administrators in the spring of 1970, their tactics were relatively quiet. The Planning Team, beleaguered after more than a decade of Harvard landbanking and eviction in their neighborhood, presented a list of demands. The team wanted the University to commit to building low and moderate-income housing in Riverside, and wanted the ability to negotiate the number of units directly with the Harvard Corporation. They also called for new family housing in Riverside to replace the hundreds of units lost in Harvard’s decades of eviction and demolition.

“In this connection,” wrote Gruson in a March 1970 letter to Pusey and other officials, “the roles of Mather House and Peabody Terrace in removing housing and closing ‘their’ streets was aired again.” Gruson was also acutely aware of how Harvard’s past development practices shaped what residents expected of it in the present. “There are groups of people who believe that only by the expenditure of its own endowment funds can Harvard ‘expiate its sins,’” he wrote in the same letter. “There is a note of ‘reparations’ creeping into the rhetoric of the situation.”

On May 30, Graham wrote to Gruson, informing him that a delegation of the Riverside Planning Team would be delivering a petition to his office on June 1.

“We will deliver the petition on Monday and expect the response of the Corporation by 5 p.m. Wednesday, June 10,” she wrote. “At that time we will return for their answer.”

The petition demanded that Harvard construct low-income housing on the Treeland site, and that in the meantime, Harvard allocate 500 Peabody Terrace apartments to families threatened with eviction or struggling to pay rent. These demands, Graham wrote, “are essential if Harvard is to demonstrate that it has a commitment, beyond words, to rectify the damage done to the low income residents of Riverside by Harvard’s expansion.”

On June 10, members of the team did return, but received no answer from administrators. Determined to make their voices heard, they spent the night in the Yard and disrupted Commencement the next day. After their protest, administrators began to take Riverside activists more seriously.

Throughout the summer, the activists continued to leverage public attention to put pressure on the University, with Saundra Graham making appearances on TV and the radio. They raised another demand, too, telling administrators in a June meeting that they wanted veto power for any future development in the neighborhood.

Tempers rose on both sides. After hearing Graham planned to make another radio appearance, Gruson chided her in an August letter: “I thought that we agreed that it would be helpful for all of us to reduce the noise level surrounding this development,” he wrote.

“What a jerk,” Graham recalls. “It was like talking to a five-year-old.”

In a July 1970 letter, Gruson wrote to WKBG-TV to “correct errors” after Graham appeared on their air, insisting Riverside was a “mixed, complicated” neighborhood for which no one group could speak. Around the same time, he told Pusey that he worried the Riverside Planning Team would demonstrate outside his office. “I think their tactic is to try to pressure us during the course of the summer into some awkward position,” he wrote.

“I don’t think they were scared,” Graham remembers. “They just didn’t like the publicity.”

In the face of mounting public scrutiny, Harvard opted to strike a compromise. It would acquiesce to activist demands by locating space for affordable apartments, but would still develop Treeland into profitable student housing.

Though Gruson had previously complained that public pressure was making it harder for Harvard to find land for affordable housing, by July he assured Pusey in a letter that one piece of land he was eyeing “might be used for low and moderate income housing without a loss by the University.” Gruson looked at multiple sites, hoping to “covertly” secure them for low bids. A site at Howard and Western got the go-ahead, and Harvard purchased it.

“At long last,” Gruson wrote to Pusey in December 1970, “the Riverside people have agreed with us on a developer for the parcel of land at Howard Street and Western Avenue.” Harvard’s approach was softening: The University had moved from dismissing the activists’ framework to accepting at least some of their demands.

Harvard still planned to build on Treeland, even if Gruson expected “a fuss when we try to build for ourselves on that site,” he wrote in the same letter. Regardless, he swore he would “make it clear that the Treeland/Bindery site is NOT available for housing for the community.”

On March 1, 1971, Harvard voted to authorize the preparation of Treeland construction documents.

Still, continued pressure from activists, and the negative publicity it threatened to generate, pushed Harvard to bend even more toward resident demands.

In a September 1970 letter, Gruson updated the Riverside Planning Team on a recently acquired Harvard property that would focus on housing elderly low-income tenants. “The University wants to encourage the idea proposed by the Riverside Planning Team,” he wrote, referring to the team’s suggestions that tenants be chosen by the community and determine the building’s management policies.

On March 6, 1971, hundreds of Boston-area women took over 888 Memorial Drive, a building used for storage on the Treeland site, and refused to leave until Harvard committed to the creation of a women’s center and low-income housing on the property. The 10-day occupation garnered intense pushback from the administration amid increasing press coverage.

On March 15, a judge ordered police to arrest the women using “whatever force necessary and not listen to those do-gooders who say ‘police brutality’”; facing the prospect of violence and legal action, they left the day after. But they were able to use a $5,000 donation they had received during the occupation to put a down payment on what would later become the Cambridge Women’s Center — to this day, the longest continuously operating women’s center in the country.

By the end of the summer, the future of the Treeland site was far less certain than before.

Gruson wrote in August to Charles U. Daly, Harvard’s vice president for government and community affairs, to float the option of building mixed-income housing on the site. Even the low-income housing the University had built on River and Howard as a “quid pro quo,” he wrote, had not been enough to quell protests.

“During the last year we were never able to deflect the neighbors [sic] demands for at least part of the Treeland/Bindery site,” Gruson added, “probably because we were unwilling to take a stand and risk another disruption during Mr. Pusey’s last year.”

In September, Harvard worked to place tenants in some of its other affordable housing sites. They passed this responsibility to the Cambridge Corporation, a community development and housing organization, which told Harvard administrators it was working with Graham to reach “all possible eligible Black residents” of Riverside.

Later that month, William S. Gardiner, Harvard’s deputy director of buildings and grounds, wrote that the best strategy might be to use Treeland for something other than housing entirely. He added: “We should be able to defend the project on its own merit, by ourselves, or else we should consider some other more viable alternative.”

Two of those alternatives could be making it into a community center or a museum, Gardiner suggested. Another possible step that he hoped would be “less controversial” than the Riverside project was building across the river in Allston.

In October, the administration notified the Metropolitan District Commission that the University had scrapped its plans. It would not build on the Treeland site “for an indefinite time.”

Graham and the Planning Team were not surprised by the decision, but they only found out when Harvard students informed them of it. “Otherwise, we wouldn’t have known,” she says.

Daly released a report a year later announcing an 18-month moratorium on further land acquisition in Cambridge. For at least that much time, he wrote, “neither Harvard University nor its agents will purchase a single piece of residential property in Cambridge” outside a defined area that hewed closely to campus. Daly wrote that this decision was based on “moral commitment, enlightened self-interest and the knowledge that ... urban institutions neither can nor should live in isolation.”

Although the moratorium later expired, the University would not buy up Riverside properties in the same way again. In this part of Cambridge, Harvard’s era of expansion was effectively over.

'Leave the City to Us'

Yvonne L. Gittens — a longtime Riverside resident and former director of the Cambridge Community Center, where she is affectionately known as Ms. G — gets several calls and texts a day. Pamphlets from real estate brokerages pour into her mailbox. Each asks if she’d sell her home — and for how much.

She sighs. “I don’t answer most of them. Today I got a text message, and instead of hitting delete, I hit redial. The guy called me back and I said: ‘Not interested.’”

“I often wonder how many of them are Harvard real estate or MIT real estate,” she adds.

In Riverside today, many buildings sport colorful siding and chic, sans-serif house numbers, bought up by enterprising developers. A handful of homes haven’t changed; they’ve been owned by the same families, many of them Black, for decades. But when properties are passed down and developers offer exorbitant amounts, some inheritors opt to sell.

After scrapping Treeland, true to Daly’s word, Harvard stopped the large-scale Cambridge land acquisition that marked the previous decades. But Riverside was still gentrified by private landlords and developers who pushed out working-class people to capitalize on the neighborhood’s proximity to Harvard.

In 1960, about 80 percent of rented properties in Riverside had a gross rent of less than $80, or $800 today. By 2000, that portion dropped to 26 percent. Until 1980, more than a third of Riverside residents were Black; now, only 18 percent are.

According to Reverend Dr. Jeremy D. Battle, the senior pastor at Western Avenue Baptist Church, many longtime Black residents have moved farther away, causing many of his former parishioners to go elsewhere instead.

“The expansion and development of Riverside,” he says, “was tantamount to the death of the Black church.”

Five years ago, at 8 p.m., police shut down a block party Graham was throwing; her neighbors had called the cops on her.

This is what her neighborhood looks like now, Graham says: new residents — many of them wealthy and white — who rarely show up to community meetings, who walk their dogs everywhere, who send their kids to private schools, who buy houses next to Corporal Burns Park and then complain about the teenagers playing basketball there, who call the cops on parties thrown by a woman in her 70s.

“It’s ludicrous,” she says. “What do they do for excitement?”

Gittens says that Riverside has filled up with people “who can afford to live in the suburbs.” She pauses for a moment and smiles: “Leave the city to us!”

When we ask Riverside residents to identify the time when the neighborhood first began to change, everyone says something different. Gittens traces change back to the 1960s, when the city widened Memorial Drive and connected Western Avenue to the Massachusetts Turnpike. Graham points to the ’80s, when she noticed white people starting to move in. Battle names the ’90s, when Massachusetts voters ended rent control policies that had been in place in Cambridge for decades; soon after, Harvard raised the rents of the 709 rent-regulated apartments it owned in the city.

Still, they all agree that Harvard, as one of the largest developers in the area, played an outsized role in reshaping it.

“Harvard was the major thing that has turned my community the way it is,” Graham says.

Many community members didn’t trust the University’s commitments to end development in the neighborhood. “They were just words,” Graham says. “You can’t trust people like that. They have no morals.”

In late 1998, Harvard announced that it hoped to turn the Treeland site, which by then held Mahoney’s Garden Center, into a modern art museum. Gardiner had recommended nearly 30 years earlier that such a move might be more acceptable than constructing University housing.

But Harvard was met with three years of resistance, during which residents convinced the City Council to place another moratorium on Riverside development. Some of them wanted the site to become a public park. At one meeting, The Crimson reported, a community member told the University: “If you build it, we’re going to bomb it.”

In 2002, the University gave up on its plans for the museum. In 2010, as part of an agreement between Harvard, Cambridge, and the Riverside neighborhood, the lot became a public park.

In recent years, Harvard has also invested in Boston-area affordable housing, such as the Harvard Local Housing Collaborative, which has put more than $40 million into the preservation and creation of affordable housing over the past two decades.

Harvard hasn’t tried to expand into Riverside for two decades — but in the neighborhood, bitter memories still linger.

Alex, a lifelong Riverside resident who wishes to be identified only by his first name, was born there in the ’80s. On a sunny afternoon, we stand on the sidewalk and talk about his home. “It’s a different community now,” he tells us. “Money came in and changed everything.”

He gestures toward the Peabody Terrace towers, visible from nearly every street in Riverside. “Harvard’s the big bad wolf around here,” he says. “They’ve got all the money, so they can push people out.”

'A Long, Long Fight'

Just across the river in Allston, Harvard owns more than one third of the land. Its 360 acres there hold the Business School, Science and Engineering Complex, hundreds of apartments, and perhaps someday, the 900,000-square-foot proposed Enterprise Research Campus. In some ways, its development strategy has been different from the widespread evictions and demolitions it pursued in Cambridge; in others, it has been markedly similar.

Kathy Spiegelman, Harvard’s associate vice president for planning and real estate, said in 1997 that “since most of the campus in Cambridge is surrounded by residential neighborhoods, and displacement of those neighborhoods is not in the university’s best interest or the realm of possibility, it was necessary to look in other places.” Harvard had started seriously acquiring land in Allston in 1989 under the moniker of the Beal Companies, a shell corporation, as they had done in Riverside decades prior.

Harvard has faced well-documented criticism over its push into Allston from residents who have raised concerns about rising housing prices and said the University has failed to transparently engage with locals.

“Harvard’s real planning is completely opaque,” says Brent Whelan ’73, a schoolteacher who has lived in Allston for decades. “What happens in public is something of a shadow game.”

As it had done in Riverside, Harvard has opted not to play the role of developer. Instead, it has contracted out private entities, which Whelan views as a move to insulate itself from accountability.

In contrast to its campaign in Riverside, in Allston, “Harvard has left residential structures intact as it expands into disused industrial space,” Whelan added in an email.

Harvard spokesperson Amy Kamosa wrote in a statement that “the University is deeply engaged with and proud to be part of our vibrant communities in Cambridge, Boston, and throughout our region.”

She added: “We benefit immensely from collaborative work with residents, organizations, businesses, elected officials and others through programs, partnerships, public spaces and other shared activities and priorities. As we look ahead to Harvard’s future in Allston and elsewhere, we are committed to ongoing engagement with the community to advance shared goals, and to ensure that Harvard’s spaces and places are lively, welcoming, and inclusive, that they maintain and enhance the unique creative culture of their neighborhoods, and contribute to a thriving, innovative ecosystem.”

But residents still criticize Harvard’s impact on the housing market in Allston.

Whelan says, “Displacement is a subtle thing when you’re not coming in with a wrecking ball.”

***

During the Pusey era, Harvard espoused the idea that its real estate construction would benefit the economic outlook of all its neighbors.

In a 1959 address, Pusey defended Harvard properties’ tax-exempt status, saying: “Their very presence has a stabilizing effect on real estate values, since there is a constant market for houses and apartments.”

He was right; property values near Harvard remain some of the highest in the city to this day. But this idea erases the underbelly of the University-as-developer, and ignores that the large-scale eviction and demolition campaign it waged on Riverside was fundamentally necessary for its profits. To build Harvard facilities and dorms, or make nearby development more attractive, the University needed to cast families onto the street and demolish their homes.

The project that would have been Treeland came and went. Longtime residents aside — and there are few of them left — most people don’t remember what happened there. At least at first, Gruson’s correspondence suggests a University confident in this: that the people they are fighting have nothing important to say, or, anyway, no platform from which to say it.

But the residents who organized against the development knew that even if their homes were not directly under threat, the impact tremors it would have left on their neighborhood were too much to let pass. When Harvard pushed its vision of what Pusey called a “city within a city,” the city on the outside — just once, in this specific way — forced the University to listen.

Harvard, too, has moved on; the people it displaced didn’t have the choice.

At the end of our visit with Graham, we thank her for hosting us, looking at the family photos covering the walls as we turn to go. Outside, the leaves are starting to turn red.

“It’s been a long, long fight,” she says. “And if you don’t want to be in it for the long haul — don’t come.”

— Magazine writer Henry N. Lear can be reached at henry.lear@thecrimson.com.

— Associate Magazine Editor Bea Wall-Feng can be reached at bea.wall-feng@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @wallfeng.