Beneath the Stars and Planets

4:18 a.m. June 24, 2022. A ringing sound in the darkness of my dorm. I fumble for my phone to check who’s calling, squinting as the bright light blinds me and illuminates my shadowy room. My window is open, and while I can’t see it at the moment without my glasses, there are more lights dotting the sky than usual. I answer the call; I’ve been expecting it.

Ten years earlier, I stared up at the night sky, deep in the woods of New Hampshire. Crickets chirped above the hiss of burning logs. My dad pointed out a shooting star, and I watched its falling fire, a crackle of energy arcing high above the mountains. I had never seen a shooting star before. I didn’t think they were even real, just a fanciful idea conjured up by the dreamers in books and movies. But there it was, a twinkle so fast you could almost miss it, right before my eyes.

There is a scene in the “Mary Poppins” novel where Mary meets Maia, a member of the Pleiades “Seven Sisters” star cluster personified as a slender, sylphic girl. I imagined her bounding gracefully across the sky, sparks of light bursting from her feet and sprinkling stars across the stillness.

Curiosity and skepticism for what really dwells in space are what initially captured my interest in astrophysics, and I decided then, at nine years old, that I could imagine a life studying astronomy. I went through my teen years with this thought echoing in the back of my mind as I threw myself into a million different extracurriculars and hobbies. I went out on a limb for college, applying as an Astrophysics major despite having very little real experience.

4:21 a.m. I hang up, still so tired that everything feels dreamlike and hazy around the edges. I’m grateful my friend called to wake me up. He had assured me over the phone that this wasn’t something I should miss. I gently shake my roommate awake and ask her if she wants to come. She mumbles a sleepy no and rolls back asleep, so I take her ID — with its swipe to the Loomis-Michael Observatory — and pull on my shoes, still yawning.

I step outside, and the moon looms impossibly large and bright between the inky silhouettes of buildings, the darkness of sky around its crescent arc faintly aglow. I step towards the road, craning my neck over the shingled roofs to see the other planets. I walk two steps, and Mars appears. Two more, and I can see Jupiter and Venus. Five in total, although I’ll need a better view if I want to see them all.

My first real taste of astrophysics was the summer after freshman year when I began to conduct research at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, or CfA. I fell into a comfortable rhythm, running new code and abusing the free coffee machine on the first floor every day. All the students were invited to a weekly research colloquium, where a researcher would present their topic of interest. Every week, I’d wander from my office on the third floor through the CfA’s maze of rooms full of space posters and sunlit corridors, grab an egg salad sandwich, and sit in the Phillips Auditorium to learn about exoplanet atmospheres or the shape of the galactic stellar halo for an hour.

One day, as I looked over the next week’s selection of talks, I glanced at a graduate student’s dissertation talk on detecting extrasolar planets. At that moment, it hit me what I was seeing: her life’s work presented in a 40-minute lecture. How had I taken for granted the ability to engage with pure science at the highest level, to witness the culmination of years of cutting-edge research and advanced study of the cosmos?

4:29 a.m. I scooter through a silent Square to the Observatory. The sky is beginning to lighten ever so slightly. The Yard exists in perpetual twilight in the hours of early dawn, and right now everything feels dim and dewy and not quite real. In the quiet morning, I feel alone but not lonely, beneath the moon and stars and planets.

My field feels a solitary pursuit at times: a lone astronomer in the night, studying things incomprehensibly vast and old and beyond our present reach. The light we receive from Earth is thousands, millions, or billions of years old, illuminating the sky from distant stars and galaxies sometimes long gone.

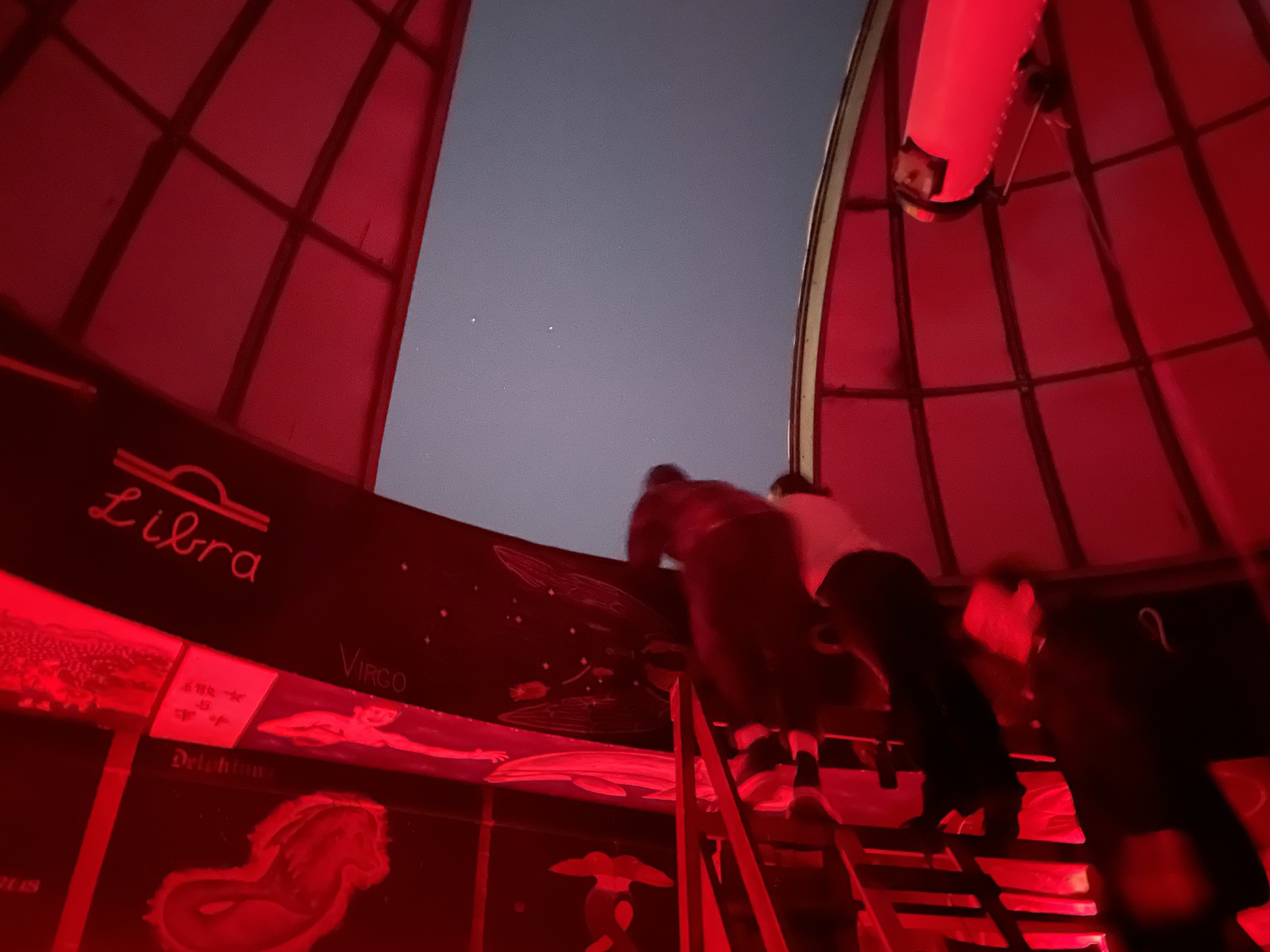

The first time I used the Loomis-Michael Observatory was on a clear February night last semester. I planned a picnic with my friends in Astrophysics. I bought cheese and crackers and figs and brought them up to the observatory. We cracked open the great gray dome, its shaft slowly grumbling open to reveal a patch of night, dotted with a singular star, defiant against the light pollution of Boston. We took turns peering through the eyepiece at that blur of light, wavy and distorted from atmospheric interference.

Finally getting to see the stars I had studied all semester felt like an apotheosis. I thought about my summer spent walking with old friends and new to the weekly colloquium talks, sharing an office with other astronomers, brainstorming ideas when our code failed, or doodling aliens on Post-It notes. It is not so solitary after all.

4:31 a.m. I walk through the Science Center, empty but for a lone security guard. I take the elevator up to the eighth floor and climb the stairs up to the observatory. I swipe into the chamber, greeted by painted constellations that swirl across cinder blocks. Dawn is almost here, and I have to squint to see the planets, but there they are, a glittering starry belt across the brightening sky.

All of this is astrophysics to me – a twinkle of a shooting star, a compiling of code, a brilliant colloquium, a picnic with friends. I feel what it is to be immersed in it all, and I stare at the stars until it is too light to see anything at all before I scooter back to my dorm and fall back into my bed and into sleep.

— Staff writer Arielle C. Frommer can be reached at arielle.frommer@thecrimson.com.